The Electronic Intifada 20 July 2004

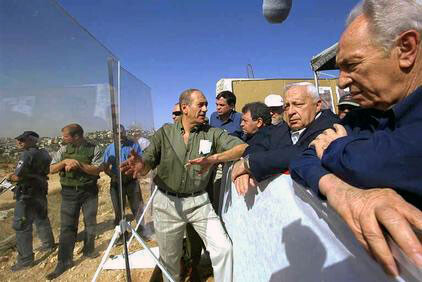

Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon is joined by then Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and then defence minister Benjamin Ben Eliezer for a tour of Jewish-only colonies near occupied East Jerusalem in 2002 during the “national unity government.” They receive explanations from then Israeli “mayor” of occupied Jerusalem, Ehud Olmert (left in green shirt).

The positive spin on the negotiations to form a Likud-Labor-led coalition in Israel is that it will create a majority government capable of implementing a historic withdrawal of Israeli forces and settlers from the Gaza Strip, and that this will somehow “jump start” the peace process. Notwithstanding the concern that the Gaza plan really aims at nothing more than continued “occupation by remote control,” as Ha’aretz columnist Amir Oren described it, a coalition headed by Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and Labor leader Shimon Peres seems more a dying gasp for Israel’s existing political order.

If Labor and Likud successfully agree on a coalition government, it will be one forged in different circumstances than their earlier partnership, which lasted almost two years after March 2001. The previous “unity government” emerged a few months into the intifada in an atmosphere of national panic. In effect key Labor leaders, like Benjamin Ben-Eliezer, who served as Sharon’s defense minister, and ex-Prime Minister Ehud Barak, openly espoused the Likud worldview that the intifada had to be crushed militarily and that there were no Palestinians with whom to negotiate. While this allowed Labor ministers to cling to office, it did not stem the historical decline of their party partly due to the numerical decline of its elite European social base.

The party split, and many Labor “doves” - those who still believed in endless and fruitless Oslo-style negotiations - joined the left-Zionist Meretz Party or bided their time. When Labor contrived a budget crisis and brought about new elections in January 2003, it suffered a major defeat. This was because its “hawkish” wing was outbid by Sharon, while what remained of the “dovish” wing did not have a credible message after the total failure of the Oslo process to bring the peace and security without sacrifice that Labor had long promised.

This time, however, rather than Labor joining up to Sharon’s Likud, Sharon is effectively joining Labor. Ideologically, this process began last year when Sharon, through his ally and deputy Ehud Olmert, shocked the Israeli public by admitting that unless Israel withdrew from some occupied territory, Jews would in a few short years be totally outnumbered by Palestinians, and Israel would cease to be a “Jewish state.” This fear of a Palestinian “demographic time bomb” was one of the key motivations for Labor to abandon its historic rejection of a Palestinian state, starting in the 1980s. However, the right, and Sharon in particular, had always scoffed at such fears. They believed that the facts on the ground created by the settler movement, plus increased immigration by Jews, would ensure Israeli control over Palestinian territory in perpetuity. The monstrous separation wall that has become so associated with Sharon was first proposed by Labor, which even today criticizes it only for its particular route. In other words, Sharon is, with his embellishments, implementing the Labor policy of “us over here, them over there.”

Naturally, Sharon’s shift has alienated much of his Likud Party. In May, his Gaza plan was soundly rejected in a referendum of party members. In June, he only got the barest Cabinet approval for a much watered-down version of the initiative by firing two ministers who had promised to vote against it. As Ma’ariv columnist Nadav Eyal put it: “Likud is burning,” as a third of its Knesset members were in open revolt against the prime minister. Sharon’s leadership is under threat from Finance Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who is more popular within the party and is outflanking the prime minister on the right. Likud, always a shaky mix of secular ultra-nationalists like Sharon, religious fundamentalists and working class Arab Jews discriminated against by the European Labor elite, now appears to be melting down just as Labor did a few years ago.

Any coalition that Sharon and Peres manage to cobble together will have to rest on the platform of declared willingness to see the Gaza disengagement plan through in some form. Such an agreement will have two immediate effects: first, intensifying the conflict within Likud and weakening Sharon even further; and second, reviving the international peace process industry, the only tangible product of which will be more frequent flyer miles for the representatives of the “Quartet.”

In the long run, the fundamental problem is that there is no partition of Palestine-Israel possible that is acceptable to sufficient numbers of both Israelis and Palestinians. The barest consensus, resting largely on fear of the Palestinian birth rate, exists in Israel for some sort of separation from the West Bank and Gaza. But it seems no two Israelis can agree on what and where to withdraw from. Even the most forthcoming proposals fall far short of what international law requires and any majority of Palestinians could accept as a minimal basis for a two-state solution. While this stalemate hardens, construction of new settlements and the wall grinds on, further altering demographics and geography such that the concepts of withdrawal and separation become ever more nonsensical.

The only thing that could break the impasse is massive and immediate international intervention to force Israel to change its ways. But as UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan recently explained when asked how Israel’s crimes in the Occupied Territories could be halted: “You would want to see immediate action by the Quartet to either stop the demolition of the houses, and that is going to take the kind of action and will and resources and confrontation that, quite frankly, today I don’t see anybody on the international community willing to take.”

In the meantime, the situation on the ground becomes worse even than that existing in apartheid South Africa. Israel’s ability to maintain control will last some years yet, but not decades. The unbroken determination of Palestinians to be free (and the events in Gaza in the past few days have by no means diminished this) guarantees that there is an end date. What is needed now is an international, grassroots movement to do the job that the Quartet won’t do, and to bring that date closer.

Ali Abunimah is a co-founder of The Electronic Intifada. This article first appeared in The Daily Star.