Challenge 16 January 2006

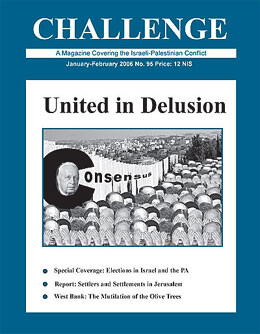

Kadima incarnates a national consensus created by Sharon. Its content may be stated simply: unilateral separation from the Palestinians. If opinion polls are to be trusted, two-thirds of prospective voters support this consensus, and it will survive its creator’s departure from political life. The public credit that enabled Sharon to shape it rested on three factors: 1) He persuaded an American president to recognize the legitimacy of annexing settlement blocs and barring the return of Palestinian refugees. 2) He succeeded in dismantling settlements (something that no former leader had ever managed to do). 3) He was able, nonetheless, to maintain a hawkish image (an asset for any Israeli politician) by sticking to the unilateral approach and by building the separation barrier. Despite public pronouncements that the latter is a temporary security measure, it is becoming clearer day by day that the barrier is intended to mark the future border between Israel and Palestine.

Sharon officially proclaimed the Road Map of 2003, issued by the international Quartet, as the programmatic basis of his new party. No one took this seriously. The Road Map was never more than wishful thinking, for it conditioned all progress on the Palestinian Authority’s ability to control security in the Occupied Territories. Since 2003, the PA’s control has only diminished (partly because ofIsrael’s actions).

The founding of Kadima did not signify, therefore, a desire to make a diplomatic breakthrough with the Palestinians. Kadima occupies the center of the newly-defined political spectrum, dispensing with the Likud right wingers, on the one hand, and, on the other, with leftists who seek a negotiated solution.

Despite boasts from the Zionist Left that Sharon was implementing its plans, the opposite was the case. The Left’s strategy exhausted itself in the Oslo Accords; its essential achievement was to create a Palestinian partner. The founding of the PA in 1993, as an ally of Israel in a new diplomatic axis including Egypt and Jordan, was the crowning moment of Labor Party policies under Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres.

Sharon never agreed with this approach. He was among the most strident opponents of Oslo. His agenda was unilateralism. The fact that Peres followed him into Kadima demonstrates the collapse of Oslo - and with it of Labor’s program.

Oslo disintegrated, let us recall, because the agreement was unbalanced in the first place, imposing Israeli superiority on the Palestinians. It included no commitment to final borders. While giving Israel the recognition it craved, it sidestepped basic issues like the future of the settlements, Jerusalem, the refugees, and natural resources. The Israeli side, including the Left, indulged in the illusion that one could live in peace with a partner that oppresses its own people, enforcing silence while Israelis thrived. The bubble burst with the failure of the Camp David talks. Two months later, in September 2000, Ariel Sharon made his infamous tour of the Aqsa compound and the second Intifada began.

The illusion of Oslo has been replaced by a new illusion of unilateral separation. If Oslo disregarded issues that are central to the Palestinian people, the unilateral agenda disregards the Palestinian people itself! It is as if we’d returned to the days of Golda Meir, who used to ask with wondering eyes, “Is there a Palestinian people?” The new Israeli consensus, applauded by so many, is founded on the notion, “What we do not see does not exist,” or on the campaign slogan of former PM Ehud Barak, “Them there, us here.” The trouble is, those whom we don’t see - those who live “there” - are a people besieged, without sources of livelihood, without control of territory, and under a crumbling local regime. True, the PA is largely the victim of its own mistakes, but Israel has had a central role in its weakening and the subsequent chaos.

TWICE Sharon succeeded in using the Labor Party to advance his agenda. The first time was in 2001, at the height of the Intifada, when he deposited the Defense portfolio in the hands of Labor’s Binyamin Ben Eliezer. In this way, Sharon left to Labor the task of destroying the PA. The chance came in April 2002, after a suicide bombing, when Israel responded with Operation Defensive Shield. It obliterated the PA’s economic and military infrastructure, imprisoning Yasser Arafat in his Ramallah headquarters, called the Muqata’a. The destruction of the PA created a vacuum, which enabled Sharon to announce that there is no Palestinian partner and that henceforth he would resolve the conflict solo. Into the vacuum, however, entered Hamas, which has since become a major force in Palestinian politics. Its ascent is part of Sharon’s legacy.

Arafat’s illness and death in November 2004 did not alter Sharon’s refusal to see a Palestinian partner. True, he did not enclose Abu Mazen in the physical Muqata’a, but the word also means “boycott” in Arabic, and in this sense it fits. The neutralization of Abu Mazen demonstrates that the problem was never Arafat, but rather Israel’s desire to reach a solution that no Palestinian leader can accept. Abu Mazen would like very much to govern the territories ceded to him, but he cannot. A big part of his weakness derives from the tough line taken by Sharon, who did nothing at all to strengthen Abu Mazen’s credit in the eyes of his people.

Here, for a second time, Sharon brought Labor to stand beside him. Labor gave up its earlier position: that Israel should aid the PA leader to gain popular legitimacy. When Peres, in 2005, ushered Labor into Sharon’s government in order to push unilateral disengagement, he accepted the assumption that there was no one to talk to. Thus he sacrificed Labor’s basic premise. From here to his joining Kadima, the path was short.

If unilateral separation seems the only way “forward,” as the new consensus would have it, this is largely the result of Israel’s behavior, which eliminated any approach that would include the Palestinian leaders.

After Sharon’s departure, Kadima will continue to cultivate the consensus he created. Just as in the Oslo period, so today, Israel has not attempted to take a straightforward road to peace, in which it would recognize the rights of the other side and act for its restoration. Zionist ideology has always refused to see the other side.

Paradoxically, the separation barrier, which literally hides the other side, may prove to be a turning point. Behind it such a mess may brew that Israel will not be immune, and those who sought security in unilateralism will discover that it too is illusion. The despair on the Palestinian side, and the desperate acts arising from this, may confront the Israeli holders of the new consensus with another kind of wall, the hard wall of reality, against which to bash their heads.

Related links

This article was originally published in Challenge, issue no. 95