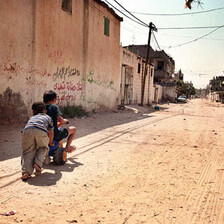

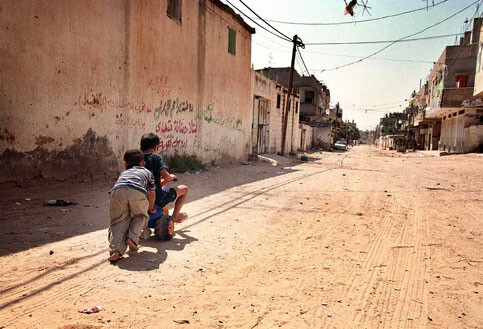

Rafah, Gaza Strip 1 December 2003

The streets of Rafah. (Ronald de Hommel)

1 December 2003 — Every time I write I marvel at how many hours it takes me to pass through the intimidation of the computer screen’s obliterate pixelation to decide that how I feel about Rafah might come with words attached.

The days are suddenly sliding full speed into winter. The sun, like a cheerful pop-up birthday card closing in the distracted hands of a child, is sliding behind the clouds. Some days it rains just enough to lay small buds of water on the taxi windows and I run between two worlds, crouching in the memory of the rain of rainy bus stops back home, the wind blowing through my clothes. But the wind is not simple wind here, it carries the emptiness of destroyed homes at the edge of town, the flat sand as obscene as an open door permitting an unwelcome dinner guest. And the puddles are not innocent but bring to mind images of sewage water surfacing after tanks have uprooted the streets and bulldozers broken the water pipes.

As winter creeps through the door uninvited, Abu Jameel grows his beard from the first day of Ramadan and doesn’t shave for Eid. I’ve seen pictures of him from years ago, and in all of them he is cleanshaven and smiling.

In the still nights of September I dragged Mohammed on long winding walks on the periphery of Rafah searching for some outlet for the dead energy of the burning afternoons, receiving informal lectures on “Rafah Culture under Occupation” from the perspective of a Palestinian family’s first son. Mohammed’s facial hair was sprouting up under his cheekbones to the dismay of his mother, for whom he was failing miserably at the requirements of a firstborn son by refusing to shave every morning and sit for hours in the unemployment office for electrical engineers. I at one point had imagined an office with a clean counter and a signup sheet with career counselors on the other side in business suits. This was cleared up for me in a few seconds.

“It’s a small lobby with a few plastic chairs. All the shebab (young men) who spent long years studying in universities, crossing checkpoints to study in Gaza or abroad and found in the end that their diplomas meant nothing, that the Occupation had decemated all the jobs they were expecting, they come and complain about their situation. They all smoke, you could get cancer by sitting in that room for too long. The same faces, always the same faces. No one finds work in the end, because there are no jobs.

“Nobody dresses nicely. Nobody shaves. If you wake up in the morning, you think about where you are in the world. If you find you wake up to no future, no possibility, then there is no reason for you to dress in work clothes; no reason to shave. If you shave and put on nice clothes, you’ll feel you’re lying to the world, making yourself look happy from the outside as though you aren’t dying inside. My mother asks me why I don’t shave. She asks why I don’t go to the unemployment office everyday and wait for a job. She doesn’t understand that there aren’t jobs.”

Rafah has an 85% unemployment since the beginning of the Intifada and its population currently includes 5,600 unemployed college graduates.

Abu Jameel’s garden has long ceased to return on the money it costs him to grow. His long hours in the garden serve as little more than an escape from the devestating circumstances of his home, partially demolished at the border’s edge. An escape, increasingly, from the devestation of his marriage, his wife who sleeps later than he’d like and spends her days too caught in listless fear to worry to keep the house clean as he’d like, and his children who play with their toy bulldozer enacting their fears, bulldozing the furniture, their parents, each other.

The plot of Abu Jameel’s life unfolds like a tragic drama. His street, Abu Jameel Street, named after his grandfather, once the richest man in the area whose grandson used to scorn farmers, walk through the street as one known by face only, the untouchable man in the suit. Abu Jameel inherited the riches of his family and built a row of forty stores and several apartments with his two cousins and married a beautiful Egyptian woman who bore him a son and a daughter. He used to take foreigners around, Israeli men and women without head scarves, whom he would drive around in his Fiat. Once he drove a Mercedes from Germany to Saudi Arabia with a childhood friend. He collected clothes from Germany, Italy, France, Israel, and worked in a posh hotel in Hertzelia, in the north of Israel.

These days fade to memories in black and white. His wife divorced him and took his children to Egypt, and he speaks with them once every two months for a quarter of an hour. He remarried a to Noura, whose patient beauty and delicate laughter failed to fill the hole his first wife left. The flourishing business section of the street — the part he owned with his cousins — has returned to dust: the demolished remains of the street’s edge, reaching Abu Jameel’s own house which was supposed to house his children in their married life.

Abu Jameel gave everything he had away until he had no more and then he exchanged his Fiat for a donkey cart, and his hotel job for his uncle’s farm. And that, too, failed to live up to expectations. A box (12 kilos) of green California peppers, raised lovingly out of the ground, returns 6 sheckels — about $1.25. And Abu Jameel continues to work the land, obsessively, even on the first day of Eid, the holiday equivalent to Christmas in America. He grows his beard. He still does not pray, he admits to no fear. One day I pray in his house in the middle of the invasion and he laughs scornfully. “People pray to calm their fears. I’m not afraid.”

He leaves Noura to raise his children but sometimes he plays with them affectionately at the end of the day, if he has the energy. Abu Jameel, who used to delight in any international guests, has been giving us a ‘dry shave’ (colloquial Arabic meaning a ‘blow-off’) lately, complaining about the difficulties of feeding vegetarians after so many months of seeming to love the company. I remember my first months here, when just having us over seemed to bring some normalcy to his situation.

Not so anymore. His depression has grown and since the beginning of Ramadan he hasn’t wanted any guests. Last night Noah and I, who both know the family for some bit of history, called ahead to see about coming over. He said welcome, come anytime, don’t worry about the time. We got there later than we should have. Abu Jameel was sick and asleep in bed and Noura came to meet us at the door, and toasted Egyptian cheese on pita bread and poured hot tea. She looked relieved to see us — she still finds comfort in people from outside. She sat down to chat and we began to unfold the events of the day.

And in the middle of the conversation Abu Jameel started shouting his wife’s name from bed. Noura ran to see what had happened and Nancy, the two-year-old, had vomited all over the sheets. As Noura ran to clean the mess, Abu Jameel stood up.

“Laura,” he said, “come here. Listen. No more of this. You can come for visits no problem but you can’t sleep here any more. No more foreigners here. You see Noura? She’s supposed to be sleeping in bed with her children, so they don’t get sick alone. No more of this. You understand?” And he went back to bed, and Noura left her glass full of tea to turn out the lights and sleep with her children.

Noah looked at me and turned down the corners of his mouth. “Maybe it was destined to be that way.” And we went to sleep uneasily, the lights on to announce the presence of a family in the house to the army 25 meters away. Bouts of shooting woke us up in the night and I turned over restless anyway, mulling through the eight months I’d known the family. It had become so unreal that I’d made it into a black and white progression of moments that chased the last moments of my waking self as I drifted into dreamless sleep.

Laura Gordon is a 20-year-old American Jew who came to Israel in December 2002 with the Birthright Israel program and proceeded, three months later, to begin work with the International Solidarity Movement in Rafah.