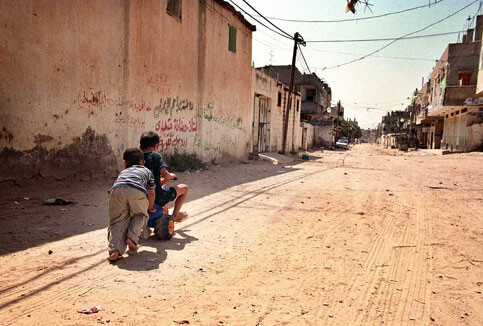

Rafah 17 November 2003

Children in an empty street of Rafah in Summer 2002 (Photo: Ronald de Hommel, 2002)

16 November 2003 — The boys were the last to come back from climbing through the remainders of crumbled buildings while Melissa and I sat long silent minutes in different corners of the sand. Local men and young boys climbed back and forth between rubble and donkey carts, collecting the usable stones from the wreckage, to make a living, searching for something to do in an impossible landscape like Hagar carrying her infant Ishmael back and forth between the deserted dryness of the mountains Marwa and Safaa searching for water. The broken stones were gleaming monotonously in the sunlight, monotonous piles blending into sand, which tumbled down into the empty half-built neighborhood a dove’s flight away.

Opposite the empty buildings, Netzarim settlement, a rolling expanse of red rooves and fat trees, surrounded in barbed wire and guarded by a sniper tower that twisted above the hill we were standing on to glare into the area. The scene was laid out like a game of monopoly, two sides scrambling to advance. Competing facts on the ground creeping towards each other. The mountains of defeated bricks on the Palestinian side stared back at us like a monument, a foreboding picture of who would win in this race. The Palestinian Authority had built the most luxurious of homes, spacious stone-built constructions, painted white, trees pushing out of the ground over the gates of gardens, only a rock’s throw away from the site we had come to visit. The wealth of the area shined like polished counterfeit coins on a losing bet. You had to wonder who would want to live here now.

On the night before Ramadan, Mohammed and I had found ourselves stranded on the wrong side of a the closed checkpoint unable to return to Rafah after translating and transcribing four-hours of long-winded men discussing what they could and could not accept in a popular peace initiative. We let the sun set and the night go by partially on purpose, sick from the monotony of Rafah’s sandy roads and the demolition that seemed to come on slowly enough sometimes that you didn’t even have to know about it if you didn’t go. If you didn’t make it a point to call your friends at the border every time you heard gunfire, you didn’t have to know whether there was an incursion that night or not.

If you didn’t make it a point to visit the sites a day later, you didn’t have to know about the devestation of families other than your own. If you didn’t try too hard to witness, the worst part of your life would be your inability to move and see new things, a restaurant with anything but felafel and kebab, a cinema, a neon sign. In the days that I let my work lose its vigor, and let an incursion pass by without notice (after months in Rafah, incursions were too common to shock anyone), and living in Rafah would begin to feel like living in Pittsburgh had before I left, sitting in the same coffee shop day after day with the same people and the same conversations, all dreaming to run, feeling I might live and die in one narrow street. Nothing more. Nothing more than monotony.

Even the incursions began to feel monotonous. The same stories. The same devastated large families with nowhere to go. The same phrases to express the anger and helplessness they felt. “We are not terrorists” and “What can we do?” and people who had worked for a decade and more to build their just destroyed homes failed to shock anymore, but rather each story felt like a shadow of fatigue on the waves of an ocean. In the first months, my heart had broken daily and with every story, fresh catharsis bleeding onto paper, revelations in bright red. Now, eight months after my first steps in Rafah, the pain is a gray weight on my stomach, always there, always there…

We left Rafah for Gaza’s wide streets hoping to climb out of the pits of sand to sit by the beach for a while and breathe. After transcribing a discussion for a popular peace initiative, a favor for a journalist friend of ours, we sauntered out of the terra cotta walls of the beachside restaurant into the nighttime streets, which full as the night before Christmas of energy, entire families taking up stretches of sidewalk on their way to to their relatives’ homes, men stopping into stores to make last-minute purchaces. The night was alive. We ate a pineapple pizza in the park outside of Pizza Inn, which sat in our stomachs like sticky cement and probably did not prepare our bodies for the fast.

Al-Zahara, in the south of Gaza City, was under invasion that night. Soldiers were searching house to house and the area was under curfew. But we were in the west.

And we sauntered down the streets to Mohammed’s aunt’s house where we were hoping to stay, but no one answered the door, and what could we expect having not called in advance, so we went back to the expanse of hotels along the beach where we might find an overpriced room to stay in. Not so lucky. The first hotel wanted passport and ID, which we had left stupidly in Rafah, so they could report our presence to Palestinian intellegence. More importantly, they wanted to know if we were married and if not, what was a Palestinian man doing with a foreign woman at night. They let us sit in the veranda outside between multicolored lights and a fountain in the middle which was switched off.

But we are people who learn from our mistakes. In the next hotel we were a married couple three months pregnant with our first child, but the staff wanted our marriage certificate and proof that the child was legitimate, and so we moved on to the al-Deira, which is somehow where we always find ourselves in Gaza. After we insisted ourselves married and from Khan Younis, and ungracefully turning down their offers to put us in their friends’ home who was also from Khan Younis; after being unable to pay $44 dollars each for a room, they consented to let us stay in their lobby, where we drifted in and out of sleep and read from their expensive selection of English books, everything from The Poisonwood Bible to Hizbolla: A History.

At 3:00 am, barely sleeping in al-Deira’s straw basket chairs, an explosion jarred me awake, something in Al-Zahara exploding. We wouldn’t find out until the morning when the army pulled out that a three 12-story apartment buildings had been blown up, a family on every floor.

On the dawn before Ramadan we ate our prefast meal on the deck of al-Deira, cheese and jam and tea on the gentle waves of the ocean. The call of the addan took us gently into the day. The winter’s wind was passing quietly through town, wrapping around our legs, taking us into the holy month. As we passed through the streets looking for a cab to take us back to Rafah, we passed long crowds of men walking the dawn’s fog into the mosques to pray.

We left al-Zahara’s destroyed buildings in the afternoon’s high sun, carefully avoiding the reaches of Netzareem’s sniper tower. As the hours of the fast neared to maghreb’s close, we left one site destruction for another, breaking fast with the family of Mahmood al-Qaed, 13-year-old martyr, shot dead with 17 bullets at one meter’s distance before being brutally beaten by soldiers on foot, while catching birds to support his family, whose father had been shot in the back in the first Intifada and left with mental problems that left him unable to work.

We left the men’s brown faces determined to find some use in the wreckage, another story forgotten already in the swiftness of the news, in the callussed weight of the hearts of people living here. The landscape had absorbed the disaster, again, as sand into sand under the indistinguishing bright sun.

Laura Gordon is a 20-year-old American Jew who came to Israel in December 2002 with the Birthright Israel program and proceeded, three months later, to begin work with the International Solidarity Movement in Rafah.