The Electronic Intifada 19 December 2023

Refaat Alareer was adamant that stories are for sharing.

If there is someone whose story deserves to be told, it is none other than my teacher and friend Dr. Refaat Alareer. Refaat deserves to have his story reach every corner of the world.

Before I get to his story, let me tell you about how Israel’s supporters have tried to depict him as “controversial.”

As soon as I posted a tribute to Refaat on Facebook following his assassination, I faced insults directed against both him and me.

There had been a smear campaign against Refaat in the US before he was killed. The campaign has continued since then.

It was the first time in my life that such a campaign had also been directed at me. I was surprised at how some people could insult Refaat, a man of high morals, an excellent academic and an ambassador of the Palestinian cause to the outside world.

Refaat had an exceptional ability to convey the voice of Palestine in English to Western and global media. He used his ability brilliantly to refute the dishonest claims made by supporters of Israel and its state ideology Zionism.

How could some people in the US insult Refaat, someone who spoke and wrote in their language and taught their language to the youth of Gaza?

We know that Refaat was not only targeted on social media but that he also received threats from Israelis. He received a phone call from someone claiming to be part of Israeli intelligence shortly before he was assassinated.

The smear campaign against Refaat cannot be separated from the direct threats against him. Nor can it be separated from his assassination.

The Western media distorted the truth about Refaat. The BBC, for example, published two contradictory remarks on the website of its Arabic service.

The first one read, “His admirers describe him as the voice of Gaza and a moderate academic.”

Others argue, the second remark claimed, that his opinions “tend to be extreme, like someone putting poison in honey.”

Controversial?

Refaat was deemed “controversial” by the BBC because he refused to do what it demanded of Palestinians.

Like other media outlets, the BBC has been focused on urging Palestinians and other Arabs to condemn what it calls “the terrorist attack by Hamas” on 7 October.

Some people have answered in a vague or diplomatic way to such questions. Some have responded by pointing to Israel’s crimes over the years and stressing that the crimes are continuing.

Refaat was different.

In an interview with the BBC, he answered the question about condemning Hamas directly and briefly. Refaat described the 7 October operation as “legitimate and moral.”

Refaat compared the operation to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The 1943 revolt in German-occupied Poland saw Jews using smuggled weapons to resist Nazi efforts to transport them to an extermination camp.

In late October, Refaat shared a screenshot of threatening messages he had received online.

By that time, Refaat and his family were homeless. Israel had bombed the building where he lived in Gaza City and caused major damage to his apartment.The tragedy is that when Refaat informed the world that he was under threat, there was no response from powerful governments or institutions. None of them seemed to hear, see or care.

Words as a weapon

On 4 December, he posted about the “genocidal maniacs invading my neighborhood and my city.”

That was just two days before Israel killed him.After the 4 December post, we all awaited news from or about our beloved teacher. The news was about his martyrdom.

Refaat was killed in an Israeli airstrike on his sister’s home in the besieged al-Daraj neighborhood of Gaza City on 6 December. The only weapons he had at his disposal were his words and his pen.

Those who knew him wept. So did many people who did not know him personally but were shocked by the horrific nature of his assassination.

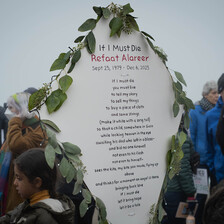

That does not mean Refaat represents some kind of trend. His final poem “If I must die” transcended Gaza and its siege and echoed all over the world.

Refaat wrote that in the event of his death, “you must live to tell my story.”Stories were vital to Refaat and to Palestine’s culture.

“I learned early in life that it’s both selfish and treacherous to keep a story to myself,” he wrote previously. “If I allowed a story to stop, I would be betraying my legacy, my mother, my grandmother and my homeland.”

In honor of Refaat, I would like to share some stories about him.

I first met Refaat in 2003. I had joined an English as a second language course that he was teaching at the Arab International Language Center next to al-Aqsa University in Gaza City.

At the time, I had just finished high school and I needed to enhance my English language skills so that I could fulfill my father’s wish. My father wanted me to study physical therapy and to later work with my uncle – a medical rehabilitation specialist – in the US.

On the first day of the course which Refaat gave, I sat at the back of the classroom, relaxed and observing the other students.

Among them were a medical doctor with a degree from a French university, engineers aspiring to work in international institutions and an administrative employee at the center, who happened to be the son of the center’s general manager.

I was the youngest among them and had not yet started university.

Reputation

I remember the moments before we met our new teacher.

We were told that he was a graduate of a British university. He had a good reputation and we all expected to benefit from the course.

When Refaat entered the room, we noticed that he was slim and young and had colorful eyes. He carried a black leather bag, a cassette player and a box of cassettes.

He introduced himself in English, telling us where he lived in the Shujaiya neighborhood, east of Gaza City. He began talking about the course’s objectives and its contents.

Then he turned his back and wrote the word “headway” on the board.

“This is the name of the book we will use during this course,” he said. “Can anyone tell me what this word means?”

A number of people responded by saying, “The way of the head.”

I raised my hand from the back row. He didn’t notice me at first but after a while asked me to answer.

“Progress,” I said.

He expressed surprise and asked me my name.

After six classes, he told me that my level was higher than everyone else doing the course. There was no need for me to continue with it, he said, as I was ready to start any university studies that required English.

It would be another four years before our paths crossed again.

Then – when I was working for the charity Medical Emergency Relief International (Merlin) in 2007 – I met Refaat at the Islamic University of Gaza. I had enrolled in a professional English for business course that he was teaching.

The course took place in the evenings. After work, I would rush to the university, sometimes coming from field visits.

For two hours every week, I got to know Refaat up close. His classes on pronunciation were especially valuable.

Once again our paths diverged after that year-long course was completed. Yet I had the good fortune to meet up with Refaat in 2011, when both of us were studying in Malaysia.

I was a master’s student in Johor, southern Malaysia, and Refaat was doing a PhD in Kuala Lumpur. Although we were in different cities, I was determined to meet up with Refaat as soon as I learned he was in Malaysia.

Humble

In Gaza, I felt that Refaat was a talented teacher. But when we met in Malaysia, I felt he was a friend.

I felt he was a friend because he was humble and lovable. He had a social intelligence.

The fact we were both Palestinian expatriates also meant there was a bond between us.

We managed to see each other regularly. While in Malaysia, we participated in many Palestine solidarity activities.

I cherish the photographs of our time together in Malaysia and am committed to preserving those memories.

I will always remember the time when I was in Kuala Lumpur and called him.

“Come on over,” he said. “I have prepared a special dish for you. You will be astonished.”

Tamer Ajrami (left) with Refaat Alareer in Malaysia. (Photo courtesy of Tamer Ajrami)

When I arrived at his place, the special treat was none other than lentil soup, a beloved traditional meal for Gazans.

We parted ways again.

In 2017, I was working with the Basma Society for Culture and Arts. I met Refaat along with a colleague who asked for his help in teaching her English.

Refaat gave us books on English grammar and phonetics.

I did not expect that the meeting would be the last time I would see Refaat. Sadly, that is how it turned out.

If I had known that it would be, I would have made the meeting longer and captured it with a photo.

The following year I traveled to the US and then in 2019, I moved to Iceland.

Since then, I haven’t visited Gaza. But I am committed to telling Refaat’s story.

Refaat felt that every moment in his life was important. Every moment should be utilized for the benefit of the Palestinian cause on the international stage.

Refaat epitomized sacrifice.

I have lost many loved ones, relatives and friends. I have been deprived of seeing others due to the arrogance of the Israeli occupation.

Losing a wonderfully creative friend like Refaat has impacted me greatly. I am not alone in feeling this way.

Everyone who knew Refaat – as a student, colleague, friend or neighbor – says the same thing.

Paying tribute to him – in the knowledge that he has been assassinated – is painful.

Tamer Ajrami is a student of political science living in Belgium.