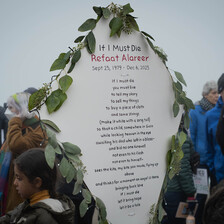

The Electronic Intifada 24 September 2024

In July, Al Jazeera released footage showing two men apparently being used as human shields in Gaza. The man on the right might be the author’s brother.

Hope is hard.

Hope is your elderly mother walking a half mile or more every few days to a café that sells Wi-Fi access cards to ask a store clerk to connect her phone to the internet.

She gets an hour of internet access for about 50 cents.

She calls me in Belgium, insisting on talking, no matter how poor the connection is. She’s desperate for news about her youngest son and my younger brother, Ahmed. She keeps asking about him, no matter what’s happening around us. She wants to know.

Sometimes the hour ends with the internet too weak for her to get any information.

Her only question is always: “Where is Ahmed?”

“He’s missing,” I tell her.

She replies, “People are fleeing constantly, moving from east to west, from one area to another. People are running like it’s the Day of Judgment. It’s terrifying. How has no one seen him yet?”

I try to comfort her, saying, “If he stood in front of you, you might not recognize him. He might have grown a beard or lost weight.”

She agrees, saying, “Yes, that’s true; war changes us all.”

But then she breaks down, crying, for her taxi driver son.

“I miss my little one. I miss the one I couldn’t sleep without knowing he was home. I cooked his favorite desserts every day. He’s the light of my life, my support, my baby.”

Holding out hope

It’s as if my mother’s mind is telling her the worst has happened.

But she clings to hope.

She asks, “How could he bear not to call me?”

I tell her, “He doesn’t have a phone; he can’t communicate.”

This soothes her, at least for a while.

A day or two passes, and then the doubts creep back in, and she cries again.

For me, it’s clear. My heart tells me that Ahmed is no longer alive.

My father and other brothers searched all the hospitals and asked all our friends and relatives. No one had seen him. It’s like he vanished into thin air.

What could keep a young man from contacting his mother unless something terrible has happened?

Could he have fled north?

But no one has seen him.

Why hasn’t he contacted anyone?

Searching for answers

The issue of the missing in Gaza is significant. There are many missing. Just log onto Facebook, and you’ll see countless posts pleading for information: “So-and-so has been missing for a while, last seen wearing a white T-shirt in such-and-such area.”

The texts are similar, but the stories are different. There are those who are mourning the loss of loved ones. Knowing they were killed at least brings an answer to the alive-or-dead question.

The missing persons are denied even the rituals of death. Their families can’t grieve or hold funerals. They’re left in a void, perhaps forgotten more than others. Even officially mourning their death will have to wait probably for four years until a court declares them dead.

My mother’s health is failing. Her blood sugar and blood pressure are high. Her kidneys will likely fail her, the doctors predict. She has already had to stay in the hospital for four days.

She tells me, “Tamer, you’re our hope. You’re outside Gaza, ask around; maybe [Ahmed’s] imprisoned by the occupation army.”

She believes that if Ahmed had known she was in the hospital, he would have come running.

Maybe my mother is right? Who could know better than a mother?

So, I hired a lawyer in Jerusalem, Khaled Zabarqa, the best I could find. He’s the lawyer who represented Ahmed Manasra who was convicted in 2016 when he was 14 of attempted murder and sentenced to 12 years in prison.

Manasra’s case has drawn international outcry with human rights experts saying it is “a stain on all of us as part of the international human rights community.”

I asked Zabarqa to check if my brother was listed among the prisoners held by the Israeli Prison Service. I didn’t hear from him for a good while, but I clung to hope.

My mother started going to the internet shop daily, asking me, “Has the lawyer replied?”

I tell her I will call her when there is news.

“Don’t worry; I will come every day,” she says. “I will sell my ring. I buy internet every day, and I won’t stop waiting. What’s new? I’m waiting.”

Days passed before Zabarqa finally told me that Ahmed’s name was not on the list of prisoners in Israel.

I told my mother that Ahmed isn’t imprisoned; he’s missing.

Maybe he’s in Rafah or Gaza, and the situation is difficult. I try to reassure her, saying he will call when he can.

Sometimes I succeed in calming her down. Other times I fail.

Hope returns

You might wonder what my father thinks about the situation.

He is a strong man, silent, accepting what fate brings.

At one point he told me: “Your mother is tired.” Without doing so, it was as if he was asking me not to take away her dream that her son is alive and will contact her.

As if my father can see her spirit fading.

People in Gaza die from heartbreak and sorrow. Hope gives the soul strength and puts light in the darkness.

I fear my mother’s tears, so I try to speak confidently, telling her Ahmed will return.

I even started an initiative, offering $200 to anyone who finds him and asked my mother to spread the word about the reward among friends.

I tell her, “Maybe he went south and didn’t want you to be sad about him leaving.”

Her hope rises, and she says, “I will tell his father to rebuke him when he comes back for making me go through this!”

I smile sadly and say, “First, let’s find him, then you can do whatever you want.”

Then, on 17 August, hope returned to all our hearts.

A picture was published with an article by Haaretz showing Palestinian prisoners used as human shields in front of a tank.

I felt Ahmed might be one of them. It makes sense. He left home heading south and may have encountered the army, which might be now using him as a human shield.

My mother was sure he was in the photograph we saw. My father seemed skeptical.

I felt joy, but then fear set in.

What happened after that?

Did the army force him into a tunnel that then exploded?

Did he refuse to cooperate, and they killed him?

Was he taken to a secret prison with no records?

I don’t know. But at least, hope has returned to my mother.

So, I sent a message via WhatsApp to Zabarqa, the lawyer, telling him, “This is my brother. The photo is not clear, but maybe you can find out what happened to the two prisoners in the photo.”

He asked, “Which one is your brother?” I told him, “The one on the right, wearing the gray T-shirt.”

And now, we wait, clinging to a glimmer of hope to ease an old woman’s heart and restore my father’s usual grace.

Tamer Ajrami is a student of political science living in Belgium.