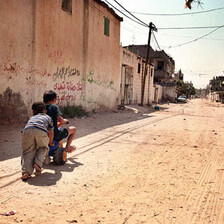

Rafah, Gaza Strip 1 December 2003

Destruction in Block O.

A few days ago I was walking down the street with a friend, going to visit his sister. We had just come from his family’s house where we ate a delicious meal, breaking our Ramadan fasts. As we turned a corner and entered another neighbourhood the illusion of normalcy disappeared. The buildings beside us were punctuated with several bullet holes. A normal sight in Rafah, bullet ridden buildings are a constant reminder that life here is not normal, as you and I who make our homes in the West, who have never seen conflict, define normal.

Along with the bullet-ridden buildings comes the reality of how they are created. Starting in the early evening and continuing until dawn there is regular gunfire — coming from any number of sources. Sniper towers surround Rafah, thereby controlling it almost completely. At almost any point in the city you could be shot and killed by a sniper. Bullets fired from the towers can kill for up to 5 kilometres.

One of my most surreal experiences is sitting on the “patio” outside one of the houses that I stay in. The house in the last line before the sandy nothingness that separates Rafah from the Egyptian border. It was once several blocks from the border however time and a great deal of bulldozing has left it next in line to suffer the same fate as its neighbours. Sitting on this patio I have shared many great moments with the wonderful family that call this home. Around five hundred meters from the house is the wall that marks the border. Along the wall is a sniper tower. Between the house and the tower is only a wasteland of sand. As we sit and drink our tea, soaking in the remaining light of the day the soldiers watch us. At any moment any of us could be shot dead. However, this is the new reality, and we continue to drink our tea.

Umm Hisham on her patio.

Yesterday I sat on the roof of a friend’s home making Ramadan sweets that we would enjoy later in the day. The invasion was going on only a few blocks from her house. A few doors away a Shaheed Tent has been erected to commemorate the death of a martyr- a man killed by a heart attack while under fire from an Apache Helicopter. My friend’s house is surrounded by shooting. We make our sweets. Eventually it is time to move inside as the shooting begins to move in our direction and it is deemed to dangerous to continue sitting on the roof. Random bullets know no targets. A young boy was shot in the head while standing on his porch by a miscellaneous bullet.

This is life in Rafah. On the surface it appears normal, but at any second this facade can be wiped away with the opening of a new round of fire from the sniper towers. Maybe this is normal and just must redefine my experience of the word. Maybe I already have. Shooting, tanks, martyrs — they have all become a part of daily life, like taking out the garbage or taking the dog for a walk. As my eyes sift through the crumbled remnants of yet another demolished home, yet another demolished life I know it is a scene that will be repeated again and again.

And yet I there is part of me that cannot fully accept this new reality, this new normalcy, for no one should experience normalcy in this way. Talking on the phone with people outside of Rafah causes my two experiences of normalcy to confront each other. As we talk about every day situations the sound of gun shots ring through the air and I am reminded that to the person on the other end of the line this is not normal, this is a completely foreign occurrence. Normal means not being afraid to walk down your street at night. Normal means not being awaken by loud, earth rattling explosions. I can only hope that life in Rafah resumes some aspects of my idea of normalcy, especially before the people here forget about what it is like completely. Forget how their old photographs tell them life is supposed to be.

Normal.

Melissa is a 23 year old Canadian who has been working with Project Hope and the International Solidarity Movement in the West Bank and Gaza for the past two months. This is her second stint in Palestine with I.S.M. Melissa has graduated with a B.A. in History and Humanities and instead of growing up and finding a real job she is living in Rafah.