The Electronic Intifada 4 November 2004

“Memorial to 418 Palestinian Villages which were Destroyed, Depopulated and Occupied by Israel in 1948.” Refugee tent and embroidery thread, 2000.

What is it like for a Palestinian-American artist to make art when each day Palestinians are suffering at home because of the Israeli occupation and the current political situation? How can art help bridge borders and open peoples’ eyes to the realities of the Palestinians? These questions find answers in the work of Palestinian-American artist Emily Jacir, and she recently discussed her work to a sold out auditorium at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Living and working between Ramallah and New York, Jacir is best known for conceptually based photography, video and installation projects that do not hide her political sympathies or ignore the highly charged atmosphere in which she lives.

Jacir has lived a bit of an unsettled existence and her art reflects this. After growing up in Saudi Arabia, she went to high school in Rome, attended undergraduate and graduate school in the United States and has had artist’s residencies in Colorado, Paris, New York, and Linz. Her work explores themes that relate directly to her life such as exile, movement and normalcy, calling into question what it means to be free while putting a personal face to the Palestinian conflict. That night was a rare opportunity for Chicagoans interested in Jacir’s work, since the one and only time her work was exhibited here was in 2002 when her “Memorial to 418 Palestinian Villages that were Destroyed, Depopulated and Occupied by Israel in 1948” was shown at University of Illinois at Chicago’s Gallery 400. That night Jacir told the story of her powerful artistic development, her motivations, and at times the risks she has taken to document life as she knows it.

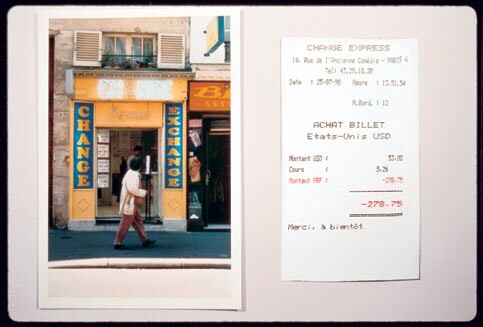

“Change/Exchange” (detail). 60 photographs and receipts, one shelf, $2.45 in coins.Photographs and receipts document the repeated exchange of $100 US into French Francs and back until only $2.45 remained in coins (coins are not exchangeable). This took sixty exchanges. 1998.

Jacir began her lecture with her first work that broke from her formal education of “pretty traditional painting and sculpture.” In 1998 while living in Paris Jacir documented her first performative work, “Change/Exchange,” which explored the “idea of translation and also what’s lost when you are transferring things back and forth.” The premise of the piece was simple: Jacir took a one hundred dollar bill and changed it into French francs. She then took the francs and changed them back into dollars and so on and so forth until, sixty exchanges later, the paper money was gone; only coins, which could not be exchanged, remained. And if you don’t believe her, Jacir has a snapshot of every currency exchange along with the receipt to prove it.

Tracing her projects chronologically, Jacir moved on to a work started that same year in Paris in which she re-enacted a cultural exchange of her own, “From Paris to Riyadh (Drawings for my Mother).” Reflecting upon a practice her mother did each time they entered Saudi Arabia, Jacir collected Vogue magazines from her childhood years there. Then on vellum paper, she traced the outlines of the models’ exposed flesh, creating abstract patterns of the negative space. You could simply interpret these drawings as criticizing a Saudi Arabian law, but for Jacir this practice reflected negatively on both countries. Whereas in one country, “the image of woman was banned” in the other “the image of woman is nothing but objectified and co modified,” which left Jacir feeling “equally repressed in both places.”

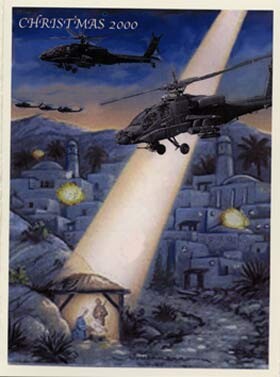

“Christmas 2000”: Political Christmas cards telling the real story about what is happening in the “Holy Land” covertly placed onto shelves of stores throughout New York City.

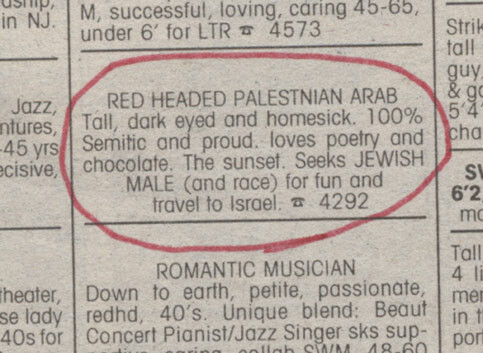

An even wider audience was broached when she had Palestinian women and men place ads for Jewish mates in the Village Voice’s personals. “Sexy Semite,” as this project became known, took place on three separate occasions from 2000-2002, but it was the last time, when it ran on Valentines’ Day, that the press took notice. Jacir’s intentions with placing such ads as “Do you love milk and honey? I’m ready to start a big family in Israel. Still have the house keys. Waiting for you,” were to “pollute the space of the personals” and to “discuss the right of return.” However, the post 9/11 press did not see it that way. Articles in the New York Post and the US News and Washington Report speculated that these were actually terrorist plots and tried to contact the Palestinian ad-placers.

Revealing the true history of the Palestinian people is another theme of Jacir’s work and can be readily discerned in one of her most well-known projects, “Memorial to 418 Palestinian Villages that were Destroyed, Depopulated and Occupied by Israel in 1948.” While living in New York in 2001, Jacir opened her studio day and night and invited people to commemorate these villages by sewing their names in English on a refugee tent. At the end of three months over 120 people from various backgrounds came. “Some were Palestinians from those villages, some of them were Israelis who grew up on the remains of these villages, some of them were just people from New York and not just artists, there were bankers that came in there after work.” And the reason for the long title, Jacir explained, “was because if they ever wrote about it in a magazine or newspaper, which they did, they would have to put what it is because otherwise, with my experience with speaking about this issue, they always try to obscure what happened or change the history.” Jacir added, “These names are not in history books,” but because of this powerful memorial, anyone who sees it will have to confront the history of these villages, all 418 of them.

“Sexy Semite” (detail). Personal ads placed in the Village Voice, of Palestinians seeking Jewish mates in order to be able to return home. 2000-2002.

One of Jacir’s most compelling projects, 2001-2003’s “Where We Come From,” centers on a variety of simple requests. She posed the question, “If I could do anything for you anywhere in Palestine what would it be?” to Palestinians living in Palestine and to those exiled in Lebanon, Syria, Europe, and America, rich and poor alike. Then with the help of her American passport, Jacir set out to fulfill their wishes. Photographs depicting what she did for them are accompanied by a text in English and Arabic explaining what the request was and what restricted the person from performing it him or herself. Most limitations had to do with the person’s identification card and the physical borders they could not cross, while others had psychological barriers which were just as restricting. Requests ranged from the everyday to more drawn out visits. One girl asked Jacir to go to Haifa and play soccer with the first Palestinian boy she saw on the street. Another man asked her to visit his mother’s grave in Jerusalem on the anniversary of her birthday. It really brings a deeper reality to the Palestinian situation when such simple actions are impossible.

When asked the next day in an interview who her audience was, Jacir replied, “Palestinians. Palestinians everywhere.” She furthered, “What I was trying to say in that piece was that the Palestinians in Lebanon are Palestinian and also living the Palestinian experience, that it’s a totally valid experience. Just like the Palestinians in the Gulf, just like the Palestinians here, just like the Palestinians in the West Bank, we’re all - they are all - all of those are Palestinian stories. They are all our story, and no one has more priority than someone else.” Unfortunately, it would be impossible for Jacir to attempt to make this piece today because of the escalating immobility forced upon the Palestinians, the Apartheid Wall, closures, and the checkpoints.

As the night wound down, Jacir shared more incredible stories of her life and work as an artist. An exile without a country, Jacir melds life with her art, and typifies what is means to be a political artist. Internationally exhibited, Jacir is a courageous young artist who creates from her heart and whose work stands strongly on its own. However, Jacir’s stories are inevitably a part of her art and consequently a part of the Palestinian experience everywhere.

Jenny Gheith is currently pursuing her master’s degree in Art History, Theory, and Criticism from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Related links: