The Electronic Intifada 1 May 2005

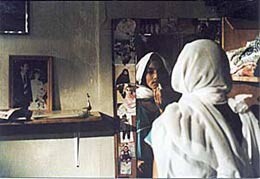

A film still from “Curfew”

For the remainder of the film, we too are confined as we observe twenty four hours in the life of the Abu Raji family, only seeing and experiencing what they do within the limits of their home. But Curfew’s focus on the everyday is far from ordinary, as this home becomes a microcosm of Palestinian society, family, and life under the occupation. Curfew’s startlingly detailed glimpse into the Palestinian reality grew out of Masharawi’s own experience of a curfew that lasted for 40 days while visiting his family in Shati, the refugee camp in Gaza where he was raised.

The first introduction to the Abu Raji household occurs because of a letter from one of the four sons, studying in Germany. With everyone gathered around, the youngest, Radar recounts how his brother has passed his exams and is leaving for a vacation in the Alps. Immediately, this freedom is contrasted with the contracted lives of the rest of his family (not even the letter can be finished). When the curfew is announced, no one appears surprised. The father actually reflects, “what does it matter, we’re sitting around anyway,” and life continues as “normal.”

Slowly the audience is introduced to the alternative ways that this family and community survive despite the curfew. Since they can’t hang their laundry outside they have a special “curfew clothesline” which they set up in the courtyard. There is also a well-structured system of trade that goes on between neighbors. When a neighbor needs milk they simply let the family know and Radar passes money through another window to his neighbor friend, who quickly passes on the milk. This complicated system of neighborly support works to symbolize not only the ongoing resilience of the Palestinian people, but the tremendous outpouring of support and communication which lies at its core.

A film still from “Curfew”

Capturing this drama is Masharawi’s cool and unobtrusive camera. Keenly recording the action, at times our viewpoint feels detached, almost as if Curfew is a documentary. Through the well-drawn characters’ eyes one only sees what they can by peering over the wall of their house — a house being demolished, a neighbor taken away by Israeli soldiers, and the birth of a child. Life goes on, even under such constricting circumstances.

Rashid Masharawi has been a well-known name in Palestinian film for almost two decades. Besides working in the film industry since the age of eighteen, Masharawi was also a founding member of the Cinema Production & Distribution Center in 1996 and has won international acclaim for numerous feature films and documentaries. Curfew was Rashid Masharawi’s first feature film and an impressive first attempt. Since its release it has won several awards, including the UNESCO prize in Cannes in 1994. While Masharawi has been quoted as saying “I am willing to leave filming the intifada to CNN,” his cinematic narrative provides a more accurate portrayal of the occupation than the news media ever could.

Jenny Gheith is a film critic for the Electronic Intifada

Related links: