The Electronic Intifada 28 August 2013

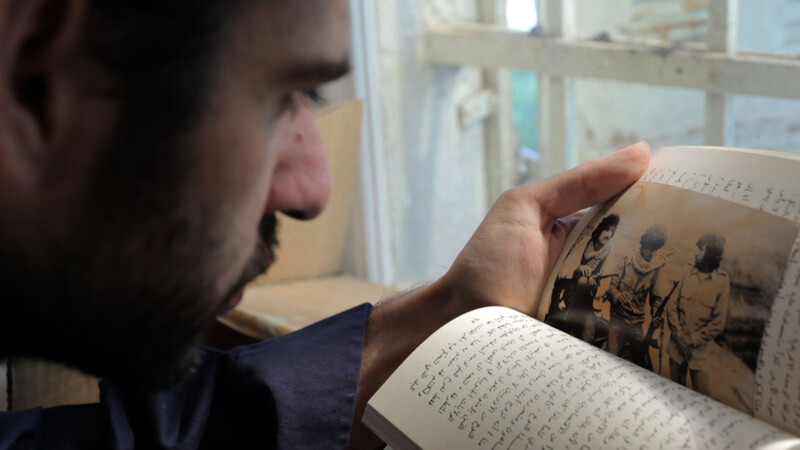

Kais Nashif in Though I Know the River is Dry.

Though I Know The River Is Dry is a short (just shy of twenty minutes), atmospheric and elegant work by British/Egyptian filmmaker Omar Robert Hamilton. That much is easy to to say.

To say more with any degree of certainty is trickier. It is certainly a film about Palestine. It is probably a film about choices, and the heartache that making them entails, and the way that one person’s choices affect those around them, the impact spreading outwards like the waves from a stone thrown into a pond.

But Hamilton’s spare script and stripped-down direction, full of hints and references, are more a series of clues than a continuous narrative. We can probably be sure that the central character played by Kais Nashif — nameless like all the other figures in the story — is a young man who has managed to obtain visas to the US for himself and his pregnant wife.

His mother, though, is furious, berating him for betraying — what? His family? The memory of his (probably politically active, probably in the armed resistance) father? His country? His brother, also apparently politically active and who has, we seem to learn from references to the source of his cigarette lighter, been jailed in the past (by the Israeli authorities?) is more forgiving. But even he presses the urgency of return.

And, it seems, Nashif’s character has returned — but to a home full of dusty, packed boxes and half-wrecked furniture. We don’t know his mother’s fate. His brother has, perhaps, again been jailed or even killed by occupation forces — his shadowy figure finally emerges from a haze to show cuts and bruises, his hands tied behind the back of his chair.

Sparse

The script is as sparse as the information on the characters. For much of the film we simply see Nashif in various telling scenarios: caressing the pregnant stomach of his wife; holding her as they fight and she weeps; walking through the streets of Ramallah and gazing at the skyscrapers and settlements as they compete to scramble into the blue sky; sorting through dust-covered boxes and finding old books and photos.

When there are spoken lines, they are often monosyllables or clipped sentences, occasionally brief snatches of argument or introspection. Through them, we grasp Nashif’s internal battle over his choices and their effects, his personal dislocation and exile, and his sense of guilt.

Why exactly the hinted-at terrible outcomes are his fault isn’t totally clear — perhaps they aren’t, really, but he is still overcome by the shame of the survivor or the one perceived as having made the individual choice.

Ambiguous

There are political overtones too. There is the obvious condemnation of the occupation and the mere fact that people are forced to make the kind of choice depicted, between a decent life and opportunities for one’s child, or struggle for one’s country. It is, of course, a dilemma familiar to anyone with Palestinian friends and acquaintances.

There are also, perhaps, other suggestions: Nashif’s ambiguous “how could I have known … help me now” is superimposed not only on images of him in modern-day settings, but also over what appears to be footage of Jewish immigrants to Palestine before the Nakba (the forced expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland) and of Palestinian refugees fleeing.

Is his uncertainty and culpability intended to represent a larger field of failure and blame, against Palestinian factions, their infighting, and the disastrous “choices” of the Oslo accords?

It’s a lot to pack into twenty minutes, but the risks that Hamilton takes in presenting us with the skeletal framework of a film and demanding that we flesh out the image pay off. Much of the imagery used — West Bank landscapes, the metal bars of Qalandiya checkpoint, old books and photos, is not new.

But its familiarity is almost necessary in this stripped-down setting; the resonances of the images and symbols help us to fill in the blanks. As such, this film may mean many other things to other people — its moods will suggest other tales, evoke other memories and emotions in other viewers. At the core is sadness, dislocation and guilt, but the details of the story may vary radically.

In a larger context, it is also worth noting that this film is another contribution to the increasing list of sure, confident, high-quality work by Arab filmmakers engaging with the subject of Palestine. It is also testimony to the enthusiasm of the Palestine solidarity community, in that — like other recent films such as Habibi and Two Meters of this Land — it owes its existence and high production values to crowdfunding.

There is, these films amply demonstrate, a growing appetite for creative filmmaking about Palestine and with Palestinian casts, crews and settings.

Sarah Irving is a freelance writer. She worked with the International Solidarity Movement in the occupied West Bank in 2001-02 and with Olive Co-op, promoting fair trade Palestinian products and solidarity visits, in 2004-06. She is the author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-author, with Sharyn Lock, of Gaza: Beneath the Bombs.

Comments

Though I Know The River Is Dry at TPFF

Permalink Dania replied on

The film is playing at the Toronto Palestine Film Festival on Oct 1 9pm with Khaled Jarrar's Infiltrators. I think Omar Robert Hamilton will be in attendance. http://tpff.ca/tpff-program-2013/

Upcoming screenings

Permalink LL replied on

All upcoming screenings are listed on the film's website here: http://www.riverdryfilm.com