The Electronic Intifada 10 November 2004

10:07PM US Central Time/6:07AM Palestine Time — Today, Yasser Arafat, Chairman of al-Fatah and the Palestine Liberation Organization and elected President of the Palestinian Authority, died in Paris from complications stemming from a blood disorder at the age of 75. Born Muhammad Abd al-Ra’uf al-Arafat al-Qudwa, Yasser Arafat was related to the Husayni family and had strong family ties to Gaza and Jerusalem. He first became active in Palestinian politics while an engineering student in Cairo in the early 1950s, where he headed the Union of Palestinian Students at Fu’ad I University (now Cairo University) from 1952-1957. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Arafat launched his own contracting firm in Kuwait and quickly prospered. He probably used his personal wealth to launch al-Fatah, the most prominent of a number of exile groups advancing armed struggle as a means of liberating Palestine.

For nearly five decades, Yasser Arafat was a larger-than-life figure for those who admired him as well as those who hated and feared him, or, to be more precise, for those who hated and feared the Palestinian view of history, justice, and politics. Since the late 1960s, Arafat was the icon of the Palestinian cause. Like Che Guevara, Arafat’s image on a poster, a T-shirt, or a television screen could convey rich and complex meanings and sentiments across wide and diverse social landscapes. With his trademark black-and-white checkered kuffiyah draped carefully over his shoulder so as to assume the proportions and shape of the map of Palestine, appearances by Arafat were almost always electrifying political events.

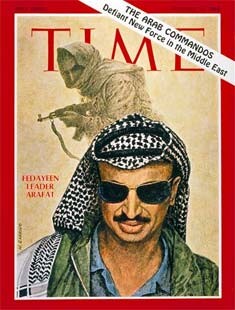

TIME magazine cover, 13 December 1968.

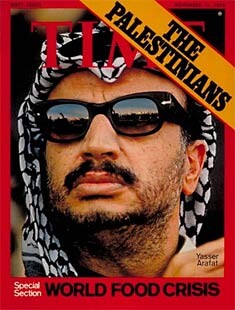

TIME magazine cover, 11 November 1974.

Many are the tales of Israeli, European, South African, and North American peace activists and journalists who waited hours to meet “Abu Ammar,” Arafat’s nom de guerre. After being whisked through the darkened streets of Beirut, Damascus, Cairo or Tunis in the wee hours of the morning, many foreigners had a chance to sip coffee in an office or parlor with the jovial, optimistic, and often emotionally explosive Arafat. Although having attained international status as a political leader of a major third world revolutionary movement, Arafat was a small man, somewhat shy, yet approachable in informal small group meetings and journalistic interviews. He could also be extremely funny and often demonstrated a self-deprecating form of humor. Although he stated for decades that he was married to the cause, he eventually wed in his 60s, taking Suha Tawil, a woman 34 years his junior, as his spouse in 1990. Later, she commented, she had “married a myth.” Since 2000, they had been living separately.

Though pro-Israeli commentators’ exaggerations of Arafat’s viciousness and bloodthirstiness, coupled with Arafat’s poor command of English and a pervasive 5 o’clock shadow, put off many Western interlocutors, no one who followed the man’s life, comments, transformations, and public appearances could deny he possessed charisma and an ability to connect with Palestinians of all classes, religions, and ideological currents, even after a series of miscalculations on his part that damaged his credibility among Arabs in general and Palestinians in particular. We send our condolences to his family and colleagues, and share the feelings of sadness of the thousands of Palestinians throughout the world.

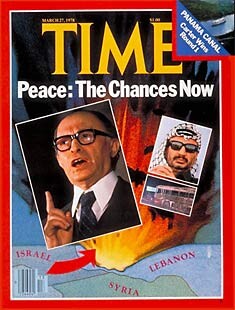

TIME magazine cover, 27 March 1978.

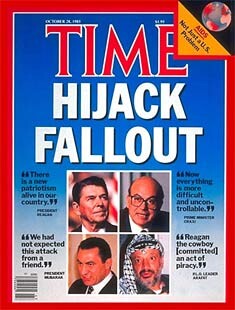

TIME magazine cover, 28 October 1985.

Few modern figures were as controversial as Yasser Arafat. Lionized by some and vilified by others, Arafat was a complicated figure. He was the leader of the PLO since before most Palestinians alive today were born. Even among his most vocal Palestinian critics, Arafat could inspire affection and loyalty in a way no other living Palestinian could. Palestinians, though, were also always his first and most vocal critics, a reality rarely conveyed by the mainstream press. And in the last decade of his life, Arafat received considerable and consistent criticism from Palestinians frustrated by the inevitable disappointments and injustices of the Oslo Accords, particularly the accelerated settlement building of this period and the lack of movement on key social justice and political issues. Arafat also received stinging rebukes from former friends and supporters in the Arab world as well as in the West for administrative corruption, mismanagement, favoritism, and a politics of patronage that made a mockery of democratic practice in the Palestinian Authority.

Arafat’s backing of Saddam Hussein following the Iraqi Army’s occupation of Kuwait in 1990 was arguably the worst of several major blunders, costing him, his people, and their cause dearly. Gulf states cut off financial and political aid to Arafat and the PLO following this decision, and with the concomitant collapse of the USSR and the emergence of the United States as the sole arbiter of Middle Eastern politics, Arafat had little leverage to resist the humiliating requirements of the Oslo peace process. Though his return to Palestine was met with joy, parades, wildly ecstatic crowds, and high hopes, the honeymoon was short-lived, largely because of the relentless and continuing Israeli colonisation, but partly because of the culture the exiled symbol brought back with him. Arafat did not return alone, but rather was accompanied by security forces, politicians, wheelers and dealers, and other hangers-on whose political styles and personal values frequently clashed with those of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza who had just waged a momentous and largely non-violent intifada from 1987-1993. The end of Arafat’s exile marked the beginning of new political and social class tensions in Palestine and the entrenchment of a political elite that, like Arafat, did not like to share power and cared little for transparency and accountability in administrative matters.

TIME magazine cover, 26 December 1988.

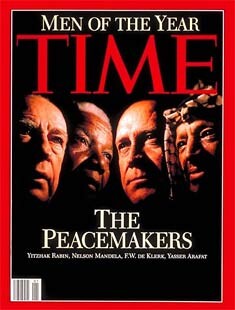

TIME magazine cover, 13 September 1993.

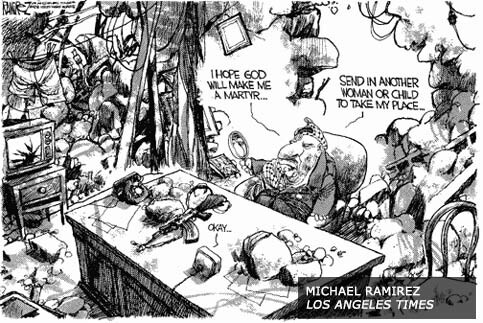

Despite his actual and figurative weakness over the last two years, Arafat was still a potent symbol of evil for Palestinians’ enemies. Even in the recent US election campaign, candidates pandering to Zionist interests routinely flaunted their pro-Israel credentials by attacking and vilifying Arafat, as President Bush did in his second debate with Senator John Kerry. The Arafat who was routinely scorned by American politicians, talk show hosts, and in thousands of American newspaper editorials for years was not a real human being, but a crude and simplistic caricature that often relied for its power on racist stereotypes about Arabs pervasive in American popular culture. The meme had been entirely conceived to distract from the real issues.

When Arafat appeared to be doing Israel’s bidding, he was elevated to the status of heroic figure and Nobel peace prize winner. When he refused to obey Israeli and American diktats, he was demonized as a bloodthirsty terrorist. As Frank Luntz, a Republican pollster, wrote in a secret report for pro-Israeli US lobbyists in April 2003, Arafat had been a great asset to Israel because “he looks the part” of a “terrorist.”

TIME magazine cover, 3 January 1994.

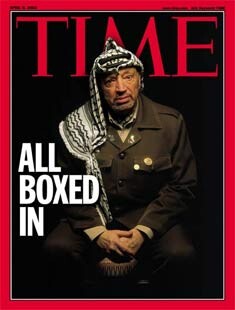

TIME magazine cover, 8 April 2002.

Arafat was routinely portrayed as a cunning puppet-master who manipulated all Palestinians, a sly political operator — a Dr. Evil-type super villain who could single-handedly stymie the peaceful intentions of the world’s greatest powers. In recent years, President Bush, following Ariel Sharon’s cue, ostentatiously sidelined Arafat, and attempted to install a new and more pliable Palestinian leadership. We have no doubt that those who worked hardest to demonize Arafat will be the quickest to celebrate his death. But we also have no doubt that they will be the most disappointed by Arafat’s demise in the long run. No longer will Israel have a convenient scapegoat on which to pin all the blame for the suffering it has caused to its own people and others through its relentless colonization of Palestinian lands and destruction of Palestinian lives and homes.

Arafat’s death will not change any of the essential underpinnings of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. There are still 3.5 million Palestinians living under a brutal Israeli military dictatorship in east Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Israel still keeps tens of thousands of heavily armed troops and hundreds of thousands of settlers in these territories, in violation of international law and UN resolutions. Millions of Palestinians still live in enforced exile, deprived of their fundamental human right, encoded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and UN General Assembly Resolution 194, to return to their own country. These stark facts ensure that suffering will continue, and possibly even escalate, until the root causes of a conflict that has taken tens of thousands of Palestinian, Lebanese, and Israeli lives are directly addressed and resolved.

Because caricatures of Arafat have dominated public and policy discourse in the United States and Israel, few Americans and Israelis can truly grasp the lengths to which Arafat and his officials went to try to work for peace in the Oslo era and also end the current Intifada, if for no other reason than to preserve their own roles and statuses in the post-Oslo Middle East. Israel may now find that, with Arafat gone, a restraining factor on the ground has departed with the deceased Palestinian leader. This may even suit Ariel Sharon and provide a pretext for ever greater Israeli violence, but it will certainly not bring peace.

For the Israeli “peace camp,” the progenitors of the discredited and disastrous Oslo regime, Arafat’s death will likely represent the disappearance of what they see as a credible partner to try to revive an Oslo-style deal in which Palestinians are given nominal or quasi-statehood within a Greater Israel, in exchange for accepting most of the settlements and relinquishing the refugees’ right of return. All these schemes were meant to secure a Palestinian signature to a status quo that is entirely to Israel’s benefit while resolving none of the basic causes of the conflict. Arafat’s death will be a setback to this discredited “peace camp,” and to such initiatives as the recent “Geneva Accord” because the Palestinian participants in this unworkable plan drew the little authority they had solely from their association with Arafat.

Although the last two years of Arafat’s life were profoundly bleak and lonely, spent under house-arrest in the company of loyal courtiers in his bombed-out and isolated muqata`a headquarters in Ramallah, he had known many moments of triumph and glory in his long and varied political career. His rise to prominence in the PLO, particularly during its period of greatest power in Lebanon (1971-1982), his speech before the UN General Assembly in New York City in 1974, as well as his important speech before the UN in Geneva in 1988 in which he formally recognized, as the head of the PLO, Israel’s right to exist and the principle of peace in exchange for territorial withdrawal, stand out not only as high points in one man’s life, but also as key landmarks in modern Middle Eastern history.

Although his political obituary was written again and again, Arafat displayed a legendary tenacity and an amazing ability to pull through at the eleventh hour, usually thanks to his remarkable skill in cobbling together coalitions and allies from very disparate backgrounds. Trapped by Sharon in the rubble of his Ramallah headquarters, though, Yasser Arafat was marginalized politically and virtually powerless militarily since the murderous Israeli attack on Palestinian cities in March-April 2002 that killed over 500 people and destroyed most of the infrastructure of the Palestinian Authority. Yet his steadfastness in maintaining dignity and decorum as the Palestinian president in the rubble of al-Muqata’a (tr. “[Ramallah] District Headquarters”) showed much of his true nature: tough, patient, cheerful, and uninterested in comfort, luxuries, and ostentation. Arafat departs the Palestinian and Middle Eastern political stage as a wraith of his former self, with no political heir apparent.

Yasser Arafat is survived by his wife, Suha Tawil, and their daughter, Zahwa.

Ma`a salaameh, yaa Abu `Ammar.

The Electronic Intifada Team

Related Links