The Electronic Intifada 10 December 2008

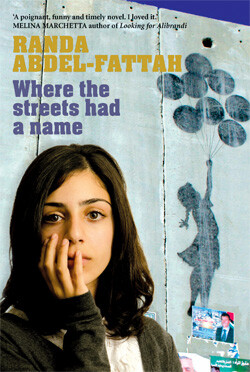

Abdel-Fattah’s third book — she’s an “Australian-born-Palestinian-Egyptian-choc-a-holic,” a lawyer, and a mom of two, all somewhat miraculously before the age of 30 — absorbs a reader immediately. This engaging family story deftly weaves together every iconic element of Palestinian disenfranchisement — land titles, checkpoints, curfews, the general frustrations of daily life — along with jokes, arguments and repeated stories which keep people going. Lost olive trees and the profound and irrevocable sense of time and haunted belonging, are in place by page 20. And they all ring very very true.

Young Hayaat of Bethlehem has a scarred face and an ebullient spirit. Written in first person, the narrative feels genuine without stretching our belief. Her older sister Jihan diets and exercises obsessively (including lifting cans of chickpeas, as weights) to prepare for her wedding. The girls have two little brothers, minor characters. Their father, Baba, carries the profound weight of the endlessly frustrated, depressed Palestinian man: “We have no way of seeing Baba’s demolition — the rubble and ruins are inside him.” Their mother grits her teeth and channels her own frustration into cleaning and cooking and bossing her children around.

Sitti Zeynab, Hayaat’s grandmother, hovers in the departure zone of endlessly repeated stories and wisdom nuggets; everyone loves her and she drives them crazy. There’s one in every family. It’s not a shy book — by page seven we have boobs and farts. The scenes are frank, stinky, funny and wistful all at once. If you’ve lived in this world, you’ll be shocked how familiar it seems. And if it’s your first entry, you’ll be welcomed.

Having witnessed the random murder of her best friend, Maysaa — a bloody tragedy suggested by the first half of the novel and revealed in flashback in the second — Hayaat has developed a numb recklessness which she now uses to steer her other best friend Samy, (a Christian boy with a dead mom and a father in prison) into the journey-quest of the book. They will travel (without telling anyone) to ailing Sitti’s old village region to bring back a hummus jar of native soil, which will somehow help Sitti survive. If one’s eyebrows are raised by this conceit, remember, they’re kids. They believe in potions and some kind of magic might still be embraced, if they could only find it.

The difficulties of their runaway journey dominate the central section of the book. Tedium and insult mark all Palestinian attempts to get anywhere in the West Bank and these kids don’t even have the proper papers. Still, they manage to make it to Jerusalem — not very far by land miles, but a gigantic leap of the imagination for “contained” Palestinians.

Their encounter with a lonely refugee Palestinian boy who pretends to be part of an international soccer team and a compassionate Israeli “peacenik” couple whom Samy distrusts, are unforgettable. You know these people exist, and you want to believe in them more than the young soldiers with guns and uniforms. But Hayaat and Samy respond to them differently.

Sitti has spoken to her grandchildren of the Jewish people, “That is the saddest part of it all. That woman who stole my home must also have kissed and played with her children. She must have also dreamed and loved.” If the central section drags a bit, we should only imagine how it feels to live such extended tiny journeys on a regular basis. The ugly wall Israel has built in the West Bank becomes its own character as it complicates what would have been normal movement between towns for citizens who knew the way inside their sleep and their bones.

The story of Hayaat and Samy, who return with soil from Jerusalem, at least, if not Sitti’s own village, and the rest of the unfurling family saga, is a story of human belonging complicated by false interferences and governmental disconnection. Encapsulated brilliantly, without too much didactic exposition, but plenty of development, the book reveals what happens when money and power and weapons distort the simple but irrevocable connections of people and land. Chosen people? Unchosen people? Righteous cause? Seizing of trees and demolition of homes? Weigh this behavior against a simple family’s dignity and longing and memory. And do the numbers, please, on the security side — Maysaa, in her absence, and the scars on Hayaat’s face which no one will let her forget, signify in a profound way Palestinians’ eclipsed losses which go on and on and on.

It is magnificent to know that the body of literature for young readers has increased so significantly with Where the Streets Had a Name. This is a story many American teachers keep looking for, to help their students grasp the seemingly endless turmoil of the occupied West Bank and Israel. Hopefully an American edition will follow shortly. Lines such as “nobody has realized that laughter sounds the same, whether it shakes its way out of a Jew or a Palestinian” could do great service for the thinking of the empathetic young.

Those of us who have long felt the Wall of Israel should come down and be shipped to New Orleans to fortify the levee will only feel that more so after reading this story. Randa Abdel-Fattah deserves our gratitude and our admiration for writing such a humane and generous book.

Naomi Shihab Nye is the author of the novels Habibi and Going Going, as well as many collections of poetry, including 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East.

Related Links