The Electronic Intifada Nuseirat refugee camp 30 May 2013

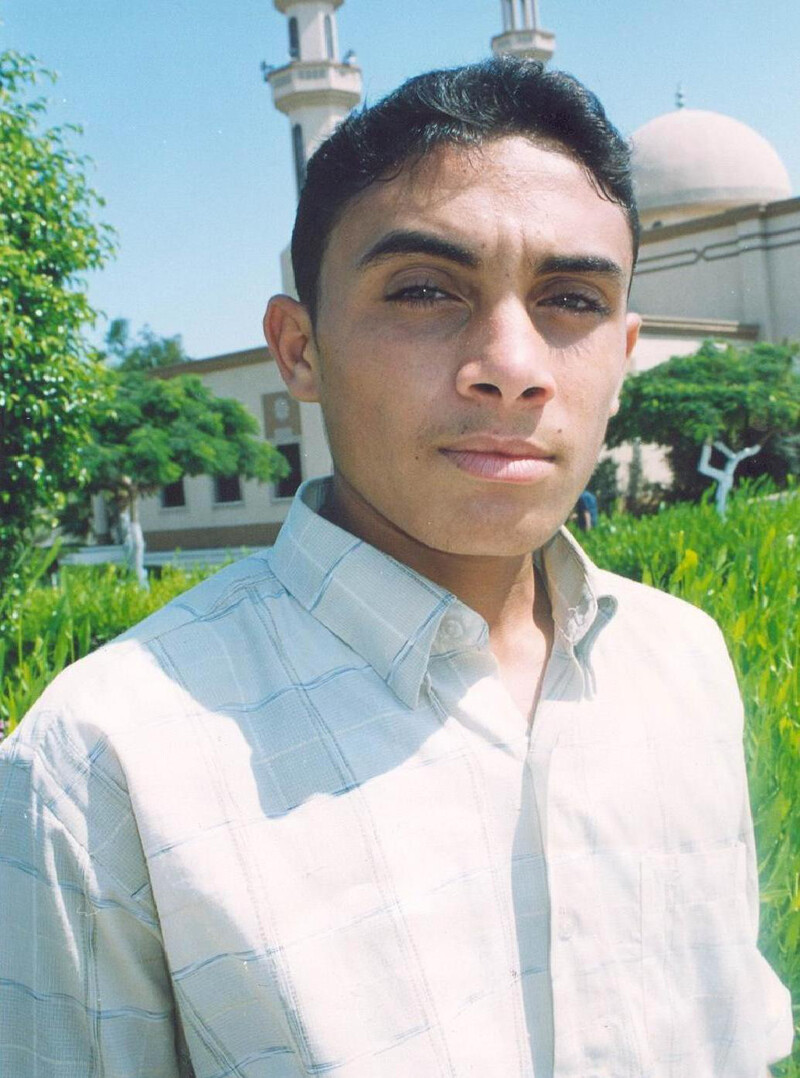

Omar Aljamal was killed by Israeli forces in 2004.

When Israel kills a Palestinian, it not only abruptly ends his or her life, it leaves deep wounds with the family that time cannot heal. And it pushes the family to threaten Israel demographically by having one more child — perhaps even more.

The years of the first and second Palestinian intifadas — not to mention the preceding years of Naksa (setback) in 1967 and Nakba (catastrophe) in 1948 — witnessed the birth of thousands of children who were named after Palestinians shot dead by Israel.

Israel’s attempts to reduce Palestinians’ numbers have never proven successful. The possibility that the “demographic time-bomb” will explode only becomes increasingly likely as Israel kills more Palestinians.

Palestinian women, such as my mother who gave birth to 13 children (excluding two who died before birth), have kept on delivering more children and naming them after those who died. My brother Omar is no exception.

The year 1986 saw the birth of my eldest brother, Omar M. Aljamal. It was a year before the outbreak of the first intifada. Omar grew up under occupation in an area called Block A, also known as al-Kalaboush, (Arabic slang for “chains” or “shackles”) in Gaza’s crowded Nuseirat refugee camp.

The Block A area, where my family still lives, was used by the British Mandate as a prison. The gate of the prison is the only exit that the neighborhood has today.

One day, during the years of the first intifada, a group of Israeli soldiers stormed Omar’s room, looking for stone-throwers under his bed. This incident stayed in Omar’s memory for years.

When he was 17, my brother joined the Qassam Brigades, the armed wing of Hamas. He joined because of the killings and the home demolitions he had seen growing up.

Before then, he had — like many of his peers — thrown stones at the Israeli army. On one occasion — when he was 15 or 16 — he was shot in the leg with a rubber-coated steel bullet. Omar did not tell our parents about his injury; they learned about it from a relative who was shot the same day and saw Omar at the hospital.

Potatoes with sugar

On 6 March 2004, I prepared some potatoes to kill my hunger. Omar rushed to the house and asked me to give him some of my delicious fried slices of potatoes. I refused.

He persisted, reminding me of the old days when he shared many dishes with me. Under pressure from my mother who almost made me feel guilty, I accepted.

That day, Omar put sugar instead of salt on the potatoes. We tried to cover up the taste of the sugar with extra salt but it was pointless. We ate the fried potatoes together.

I didn’t know that this dinner would be Omar’s last.

Shot “in front of my eyes”

The next day dozens of Israeli military vehicles invaded al-Nuseirat, which Ariel Sharon, Israel’s prime minister at the time, called the “den of wasps” for the leading role its residents had played in the first and second intifadas. Omar was shot. Six bullets hit the front right side of his body.

Saber, one of his friends who witnessed the shooting, described it later with tears: “Omar, Khaled and I entered the orange orchard to the east of the refugee camp. We wanted to make it to al-Bureij refugee camp as some people reported the presence of Israeli military vehicles there. As we walked in the orchard, snipers who were hiding in a building that was under construction in the middle of the orchard started shooting at us. Omar fell first, grabbing his AK-47.”

Saber, a father of three, still visits the shared grave of Omar and Khaled.

“Khaled tried to comfort Omar by placing his head on his grenade pouch. He was shot next to him in front of my eyes,” Saber told us on several occasions.

“Surrounded by snipers”

“I tried to grovel to get medics to evacuate them,” Saber told us. “I was shot at, but I managed to leave the orchard eventually. I begged medics to get in to rescue them, but none of them was willing to do so. The area was surrounded by snipers and tanks.”

The news of “two young men” being shot to death spread like wildfire in the alleys of the refugee camp. Saber, feeling helpless, decided to go to the orchard to get them out. He knew what the consequences could be, but he feared nothing as the image of his two close friends bleeding next to a tank stationed beside a house with snipers inside kept jumping in front of his eyes.

“As I tried to move towards them, I was shot at. I got closer to them, but I was shot near them,” Saber recalled.

Medics finally managed to get the three of them out of the orchard. Omar and Khaled were dead, Saber critically injured. The resilient refugee camp, once a home for Omar and Khaled, received the news of their death with shock.

That day witnessed the killings of 14 Palestinians from the adjacent Nuseirat and al-Bureij camps.

The way my parents were told of Omar’s death was no different to the way the families of all 14 victims were told.

One of Omar’s friends told my father that Omar had been wounded in the leg but was in the hospital and doing OK.

My father did not speak a word. We drove to al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital. As we entered the main gate, we were received by some relatives and friends. They hugged my dad, with tears falling from their eyes. My father was regarded as the “father of a martyr.”

Saber later recalled: “When I woke up two weeks later at the hospital, I asked about Omar and Khaled. I was told that they are ok, recovering from injuries, the same as me. But when I left the hospital, I was told the shocking truth.”

How will we explain?

The younger Omar.

Two years later, my mother delivered another boy and, as expected, named him after my eldest brother. So I ended up with two brothers named Omar. One is dead, the other is not.

One is my eldest brother; the other is my youngest brother. One used to take care of me when I was younger; the other one is being looked after by me now.

I am officially the eldest brother now. But I am not really. Omar, my youngest brother, regards me as his eldest brother. I regard the “real” Omar as my eldest brother.

“My friends are going to visit us,” Omar, the youngest in our family says, when he learns that some of my elder brother’s friends are going to visit.

Had he lived, my elder brother Omar would have turned 27 this week. His birthday is 30 May.

At some point in his life, my younger brother will start asking questions: Why was I named after my brother? Why do both of us have the same name? Why did I think for a long time that his friends were mine? Why did Israel invade the “den of wasps” and kill 14 Palestinians, including Omar, in March 2004?

How will we answer these questions?

Images courtesy of the author.

Yousef M. Aljamal is a Gaza-based blogger and co-translator of The Prisoner Diaries. His website is www.yeljamal.wordpress.com and he can be followed on Twitter: @YousefAljamal.