The Electronic Intifada 7 March 2019

Black Panther founder Reuven Abergel at his home in Jerusalem with the logo: “Enough with poverty!”

Gila learned about the Nakba long before she was ever introduced to her own history with Israel.

“I learned more about the Nakba from Israeli liberals than what they were willing to tell me about what Jews did to Jews, because they were all a part of it,” the 30-year-old Mizrahi Jew of Iranian descent said.

The Nakba – Arabic for catastrophe – refers to when Israel was established upon the expulsion of more than 750,000 Palestinians in 1948.

Gila lives in Jerusalem and asked to use a pseudonym to protect her identity. She said she only began understanding the history of the Ashkenazi (Central or Eastern European Jewry) oppression of the Mizrahim (Jews originating from the Middle East and North Africa) after being introduced to former members of a little known, albeit hugely influential, movement: the Mizrahi Black Panthers.

The story of the Mizrahi Black Panthers is rarely told but offers a fascinating insight into Israel’s intra-Jewish tensions and discrimination.

With general elections approaching in Israel, and many Mizrahim waiting to cast their ballots for right-wing politicians – the existence of a group of enlightened and politically engaged Mizrahi youth who attempted to radicalize their community and challenge the ethos of Zionism seems almost unimaginable now.

Formed in 1971 in the Musrara neighborhood in Jerusalem, the Panthers consisted of mostly second generation Mizrahi teenagers and youth demanding equal rights and an end to widespread racism and discrimination against their community in Israel.

For a few years, their movement spread throughout Israel and developed into a full-scale anti-Zionist movement that partnered and organized with Palestinians.

“It all started from the pain”

“In our schools we only learned about the Jewish European history,” Gila told The Electronic Intifada. “They [the Black Panthers] were the first ones to talk to us about the kidnapping of Mizrahi children and how Israel conducted medical experiments on them.”

In the 1950s, shortly after Israel’s creation, thousands of babies, largely from newly arrived Jewish Yemeni families, disappeared from hospitals, a mystery that has yet to be fully explained.

Some of them are believed to have died during medical experiments conducted in Israeli hospitals without the families’ consent. Others are believed to have been kidnapped and put up for adoption to Ashkenazi families.

“We were never allowed to open this Pandora’s box,” Gila said. “The information was strategically hidden from us.”

But the missing babies were just the tip of the iceberg for a community who long suffered systematic discrimination in Israel. At the time of the founding of the Black Panthers, Mizrahi communities in the country had faced decades of widespread poverty, discrimination and neglect.

“The movement came from the people who were suffering. It all started from the pain,” Reuven Abergel, a co-founder of the group, said, his legs crossed, leaning back on a chair in his modest home in Jerusalem.

“The reality was so hard. We didn’t have time to sit and plan. We protested because it was a response to the difficulties we faced in our everyday lives,” the now 76-year-old said.

“We filled up the prison cells”

Abergel was the oldest founder of the group, at 28. The other founders, Saadia Marciano, Charlie Biton and Kokhavi Shemesh, were in their early to mid 20s at the time.

Their community was seen by the mainstream Ashkenazim as “primitive” and an “ethnic problem” for the state of Israel, according to Sami Chetrit, a Hebrew poet and Mizrahi scholar who wrote a book on the Mizrahi experience in Israel titled Intra-Jewish Conflict in Israel: White Jews, Black Jews.

Chetrit told The Electronic Intifada that at least 55 percent of Mizrahi children dropped out of school in Israel at the time of the founding of the Black Panthers. Eighty percent of welfare-supported families were Mizrahi, while an Ashkenazi family earned 30 percent more than a Mizrahi family.

In neighborhoods like al-Musrara – which before the 1948 forced expulsion was an affluent, largely Christian Palestinian area that included Muslims and Jews – the numbers were even higher.

“Kids were just on the streets and no one really cared,” Chetrit said.

“From the first day we got to this country, we filled up the prison cells,” Abergel, a Moroccan-born Mizrahi who wound up in Musrara, said. “In our neighborhood, people were living in fear of the establishment. They were putting their heads down and not wanting to cause trouble in fear they would be beat up [by the police] or arrested.”

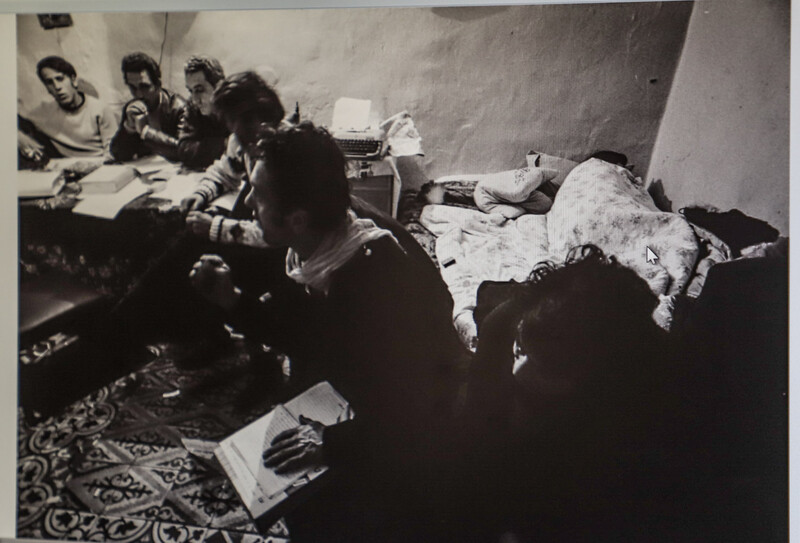

Young Panthers meet. The photo is part of Abergel’s personal collection. The group would often meet at Abergel’s house in Musrara, the area where Israel’s Black Panthers were founded.

The Mizrahi migration to Israel turned families and communities upside down, Chetrit said.

“It was not just quantitative poverty; they were also deprived of their families and structure. The family and community structure that was so strong in their countries of origin completely collapsed.”

“People [Mizrahim] who came from very stable communities for many years found themselves living in slums. It all happened in front of your eyes, within four or five years, hundreds of thousands of people suddenly had no community. Their whole lives collapsed,” Chetrit said.

Men who could no longer adequately provide for their families experienced widespread unemployment and depended on finding work at the “labor markets” where Mizrahim were chosen and hired often for just one day as laborers, according to Chetrit. The Mizrahi laborers called these markets the “slave markets.”

Women, who had typically not worked in their countries of origin, resorted to cleaning houses, cooking or doing menial housework for Ashkenazi families.

In Jerusalem, the inequalities between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi neighborhoods were even starker than in the rest of the country.

“You could literally just walk up the hill, cross the street, and there’s an affluent Ashkenazi neighborhood, or they [Mizrahi youth] were forced to watch them build new housing for Russian Jews who were preparing to migrate in the 1970s,” Chetrit explained to The Electronic Intifada.

“They had to live with these inequalities every day. They could see it and touch it. So for them [the Black Panther members] that was very upsetting and inciting. They could see no one actually cares about them, and they are forgotten.”

Preventing Palestinian return

The Mizrahim and Sephardim (Jews originating from Spain or the Iberian Peninsula who are often categorized with the Mizrahim owing to their shared histories) make up just over half of the Israeli Jewish population.

In the decades after Israel was established some 850,000 Mizrahim either fled or migrated to the newly established state from various Arab and Muslim countries, including Iran, Tunisia, Syria, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco and Yemen.

The Ashkenazi-controlled Israeli government housed many of these new immigrants in Palestinian homes that stood vacant after their owners were expelled by Zionist militias during Israel’s creation.

“In the eyes of the government, they wanted to literally occupy the houses and make sure no Palestinian came back,” Chetrit said.

Thus many Mizrahim found themselves in Palestinian homes in Ramla, Jaffa, Lydd and Haifa – now mixed cities. And inside confiscated Palestinian refugee homes, the Israeli government constructed walls to create more rooms in order to settle five or six families into one house.

The formerly affluent Palestinian neighborhood of Musrara, where the Black Panther movement was eventually founded, was thus transformed into a Mizrahi slum after its Palestinian residents were expelled.

According to Chetrit, in Wadi Salib, a pre-1948 Palestinian neighborhood in Haifa, the Mizrahim were “living everywhere, sometimes on the roof or the stairs.”

These conditions led to the Wadi Salib riots in 1959, considered to be a precursor to the Black Panther movement, when Mizrahi Jews participated in widespread street protests against discrimination and clashed with police.

It was during this same decade when thousands of Mizrahi children – mostly from Yemen – disappeared from their families. Several inquiry committees established by the Israeli government over the years have backed up accusations of medical experiments and negligence causing the deaths of hundreds of children – the scale of which, however, has still not been fully addressed.

Thus, by 1967, the conditions for widespread discontent were well established.

“Nothing to lose”

The 1967 war, when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip (as well as the Golan Heights and Sinai Desert), also played a major role in the Black Panthers’ formation. In part, this was due to the economic boom following the war, which exacerbated Ashkenazi-Mizrahi economic disparities.

The war “had a central role in speeding the process of disappointment among Mizrahim, and marked the beginning of a growing class and culture consciousness, until finally leading to a crisis in confidence, manifest in a growing population of second generation Mizrahim who had been gradually pushed to the political margins,” Chetrit writes in his book, Intra-Jewish Conflict in Israel.

A Mizrahi Black Panther poster from the 1970s reads: “Until when will 10 people have to live in one room? / The Panthers”

The boundary areas – near the 1949 armistice line with Jordan where many Mizrahim had originally been settled in camps that eventually became towns or suburbs – were opened following the war. For the Mizrahim it meant that “our day-to-day experiences were not with the privileged Ashkenazi Jews who lived in nice neighborhoods,” Abergel said, “but with the Palestinians who lived all around us.”

The 1967 war also changed the social order in Israel, Chetrit said. The Mizrahim were “artificially pushed up the social scale by an introduction of a new status [Palestinians in the newly occupied territory], lower even than that of the Israeli Arabs [Palestinian citizens of Israel].”

Despite the emergence of this new social order many Mizrahim still developed their political thinking.

According to Chetrit, the young Panther members, who spent most of their time on the streets, were influenced by members of the Matzpen movement, a revolutionary socialist and anti-Zionist movement in Israel, founded in 1962 and consisting of mainly young Ashkenazi Jews.

The Matzpen members would come to Musrara where the young activists listened to rock music, read revolutionary texts and smoked hashish together at the Ta’amoun coffee shop. The soon-to-be founders of the Panther movement, having dropped out of school at very young ages, sat and listened to the activists sharing stories about Che Guevara and revolutionaries around the world, “absorbing everything like a sponge,” Chetrit said.

But it was in the Black Panthers and the struggles of Black Americans in the United States that the young Mizrahim could see their own reality reflected back at them.

It was a “nothing to lose” situation, Chetrit said. “There was very deep poverty, dropouts, children on the streets. Fathers are not around. The community is collapsing. Then they hear all of these stories about movements around the world. The Black Panthers appealed to them,” he said.

Operation Milk

Their first planned demonstration in March 1971 resulted in a wave of preventive arrests, with police detaining 17 activists after denying them a permit to hold the protests. A counterprotest, however, led by Abergel who was not arrested at the time and families of the arrestees succeeded in securing their release.

“It was the first time since leaving Morocco that we felt a little triumph,” Abergel told The Electronic Intifada.

The Panthers then organized a hunger strike at the Western Wall, Chetrit said, leading to a well-publicized meeting in April between the Panther members, including Abergel, with then Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, who famously described the young activists as “not nice people” following the meeting.

The movement and its aims quickly spread throughout Mizrahi neighborhoods in Israel, with numerous chapters established throughout the country. The protests continued in Jerusalem, attracting thousands and sometimes triggering violent clashes with police.

In June 1971, the group published the first issue of its magazine Dvar HaPanterim HaSh’horim (Words of the Black Panthers).

“Our organization was formed on a backdrop of accumulated bitterness since the first European settlers arrived in the country,” an editorial states. “Our organization is the first manifestation of the Jews of the Middle East’s resistance.”

The first time the Panthers took a clear stand against Zionism, Chetrit noted, was in 1972 while protesting a World Zionist Congress meeting in Jerusalem. The Zionist movement was the cause of their socioeconomic conditions in Israel, the Panthers said ahead of protests that saw renewed clashes with police and several preventive arrests targeting the movement’s leaders.

In a flier passed out to protesters the organizers stated: “If you are attacked by the police, use all means at your disposal!” Others disrupted the World Zionist Congress meeting by placing anonymous phone calls claiming that a bomb was planted in the building.

In March that year, the Panthers carried out an action called Operation Milk in which activists, led by Charlie Biton, took milk bottles from the doorsteps of homes in the affluent Rehavia neighborhood and distributed them to poor Mizrahi families.

Attached to the bottles were fliers reading: “Operation Milk for the children of poor neighborhoods. These children do not find every morning, next to the door, the milk they need. On the other hand, some dogs and cats in the rich neighborhoods have milk every day, and in plenty.”

The members would also steal oil from warehouses and distribute it to poor Mizrahi families.

“Supporting each other”

For all their activity, what evoked the most fear in Israeli leaders was the connection to Palestinians, according to Chetrit. That, he said, was one of the chief reasons the movement was targeted and eventually eliminated by Israeli authorities.

According to Chetrit, David Ben-Gurion, the first Israeli prime minister, had been apprehensive about the possible relationships that could form between the Mizrahim and Palestinians in Israel, many of whom lived in the same neighborhoods, since the early years of the state.

Ben-Gurion had gone so far as to write letters to Israeli school teachers warning them of the “Mizrahi youngsters,” and encouraged teachers to “divide them [from Palestinians], and always remind them of their Jewishness, and remind them that this makes them different,” Chetrit said.

A Mizrahi Black Panther protest poster from the early 1970s addresses Israel’s prime minister at the time, Golda Meir: “Golda, Golda / Fly away / We’ve had enough of you.”

The Panthers saw their struggle as being intricately linked to Palestinians. “It wasn’t like we were fighting for Palestinian rights – not in the way the privileged [Israeli] left-wing does now,” Abergel told The Electronic Intifada. “But we understood that when we’re fighting for Palestinian rights, we’re also fighting for our own rights.”

The Panthers developed connections with the Palestine Liberation Organization as early as 1972 and recognized it as the “legitimate leaders of the Palestinian people.”

“We had talks, and we understood their need for independence and to eliminate the occupation, and we agreed that the problems with the Mizrahim and of the Arabs are intertwined,” Kokhavi Shemesh, one of the founders of the movement, is quoted in Chetrit’s book as saying.

“There will be no equality and no chance for the Mizrahim as long as there’s occupation and a national struggle, and on the other hand, the national struggle will not be over so long as the Mizrahim are at the bottom of the ladder, and are practically an anti-Arab lever,” he adds.

Charlie Biton and Kokhavi Shemesh were the first Israelis to ever meet Yasser Arafat, then head of the PLO, according to Chetrit, and the Panthers developed relationships with various members of the Fatah movement in the occupied West Bank.

“If the police were after them, they would run from them and hide in Palestinian homes,” Chetrit told The Electronic Intifada. “They were really supporting each other. This was a very radical movement.”

“The less Arab you are, the more Israeli you are”

If the 1967 war created them, the 1973 war “put an end to the Panthers as we know it,” Chetrit said. “There were no more mass demonstrations in Jerusalem. There were no more solidarity demonstrations. It was the end of a radical period.”

According to Abergel, Israeli authorities flooded the movement with informants, and even friends of Panther members were targeted for arrest.

“People were scared to hang out with us or speak to us because they could be arrested by the police,” Abergel said. “They [Israeli authorities] worked on isolating us from the rest of our community.”

Despite the crackdown and their ostracization, after the Panthers’ meeting with Golda Meir a government committee was established to investigate poverty. As a result, Israel’s 1972 state budget – nicknamed the “Black Panther budget” by Israel’s parliament – was tripled in all areas dealing with education, welfare and healthcare.

The Panthers dispersed. Some joined left-wing parties in Israel’s parliament. Charlie Biton joined Hadash, a Palestinian-led communist party in Israel. Abergel, meanwhile, continues his work in social justice, providing tours around Jerusalem to explain the historical realities of both the Mizrahim and Palestinians.

Despite the Panthers’ efforts, the Mizrahim did not become radicalized. Abergel said that ultimately Israel was successful in using Palestinians as a tool to force the Mizrahim into identifying with their Jewish over Arab identities.

“They [Israel] would just shut up the Mizrahi struggle because the Palestinians were painted as a bigger threat, manipulating Mizrahi people into joining with the Ashkenazim,” he said.

“That’s why the Zionists will never stop their policies and operations on the Palestinian people because they know that if they ever become quiet on the Palestinian issue, that’s when internal [Israeli] problems will arise.”

Certainly, educational disparities between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi communities persist. In 2015, just under 29 percent of second-generation Mizrahi immigrants had a university or college degree, compared to about 50 percent of Ashkenazim. The wage gap between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi workers in Israel also remains stark.

There is a clear formula in Israel, Chetrit added: “The less Arab you are, the more Israeli you are.”

“So you have to erase that image in the mirror every morning,” he said. “And you start to hate yourself. Women start dying their hair blond to get rid of any signs of Arabness. They wear a Star of David pendant around their neck, and when you see an Arab, insult them. So you can really feel like you’re Jewish.”

Nevertheless, Chetrit said Israel did not succeed entirely. There is a new wave of young Mizrahim, he told The Electronic Intifada, who are returning to the Arabic language and their Arab identities as poets, artists, filmmakers, musicians and even academics.

Gila said she would not have the same identity or knowledge she has were it not for the Black Panthers.

“For us [left-wing Mizrahim], the Panthers were the ones who paid the highest price,” she said. “They gave us the voice, the vocabulary and infrastructure. They gave us everything we do and write today. They are heroes for us.”

Jaclynn Ashly is a journalist based in the West Bank.