The Electronic Intifada 8 December 2023

A Palestinian woman waves a Palestinian flag ahead of a protest in a tent city along Gaza’s boundary with Israel, demanding to return to their homeland, east of Gaza City, 29 March 2018.

APA imagesWeeks before Palestinian writer and revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani was assassinated by Israel in 1972, a journalist asked what death meant to him.

He answered: “Of course, death means a lot. The important thing is to know why. Self-sacrifice, within the context of revolutionary action, is an expression of the very highest understanding of life, and of the struggle to make life worthy of a human being.”

Kanafani’s tragic end – and those words of his in particular – came to my mind almost immediately when, on the evening of 7 December, I received the painful news that Refaat Alareer, like Kanafani before him, had been murdered by Israel along with members of his family. In Refaat’s case, his brother and sister and four of her children. In Ghassan’s, his sister’s daughter, his beloved niece, Lamis.

The two men shared a resolute commitment to the Palestinian people and their cause. Both believed in and spoke about Palestine as a universal human issue. They had an urgent desire to record and propagate Palestinian culture and stories, and a fundamental belief in the righteousness of Palestinian resistance in all its forms.

Both men studied literature. They were generous and passionate educators and writers. They also both spoke English with sardonic humor and eloquence and did not suffer fools or opportunists gladly. This combination – an unshakable commitment to their cause and the means to powerfully express that position in English to a global audience – is exactly why they were such a threat to the Zionist settler-colonial project.

Neither man was involved in fighting militarily, but both wrote about and understood the central role of literature, both in the Zionist colonization of Palestine and, crucially, in resistance to it.

“Palestine was first and foremost occupied in Zionist literature”

As Refaat explained in a 2019 lecture, when discussing Palestinian poet Fadwa Tuqan and the role of cultural resistance:

Of course, we always fall into this trap of saying, “She [Fadwa Tuqan] was arrested for just writing poetry!” We do this a lot, even us believers in literature … [we say], “Why would Israel arrest somebody or put someone under house arrest, she only wrote a poem?” So, we contradict ourselves sometimes; we believe in the power of literature changing lives as a means of resistance, as a means of fighting back, and then at the end of the day, we say, “She just wrote a poem!” We shouldn’t be saying that.

Moshe Dayan, an Israeli general, said that “the poems of Fadwa Tuqan were like facing 20 enemy fighters.” … And the same thing happened to Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour. She wrote poetry celebrating Palestinian struggle, encouraging Palestinians to resist, not to give up, to fight back. She was put under house arrest, she was sent to prison for years.

And therefore, I end here, with a very significant point: Don’t forget that Palestine was first and foremost occupied in Zionist literature and Zionist poetry … It took them years, over 50 years of thinking, of planning, all the politics, money and everything else. But literature played one of the most crucial roles here … Palestine in Zionist Jewish literature was presented to the Jewish people around the world … [as] a land without a people to a people without a land. Palestine flows with milk and honey. There’s no one there, so let’s go. … And there were people — there have always been people in Palestine. These are examples of how poetry can be a very significant part of life.

The thing that perhaps connects Refaat and Ghassan above all in my mind is the fundamental choice they both made. The choice to stay in situations in which the likelihood of them being killed was high.

Refaat was a highly educated academic, a specialist in English literature. If his primary objective had been to secure a life outside Gaza for himself and his immediate family, it could have been achieved. Likewise, by the 1960s, Kanafani was a celebrated novelist, a cultural figure of regional renown with a Danish wife, Anni.

An escape route – and therefore a more comfortable, safer trajectory for both of their lives – was clear and within their grasp. Yet, like the unnamed author of the letter in Kanafani’s moving 1956 epistolary short story, “Letter from Gaza,” both men chose to stay amid “the ugly debris of defeat … to learn … what life is and what existence is worth.”

People are generally divided into combatants and spectators, Kanafani once explained in a letter to his niece Lamis. He had “chosen not to be a spectator, and this means that I have chosen to live the decisive moments of our history, no matter how short they are.”

Just like Ghassan, Refaat was no spectator. Until the end of his life, with humor, with passion and with dignity he fought as a combatant in his own way against the monstrosities and lies of Zionism.

The act of resistance, John Berger once wrote, is “not only refusing to accept the absurdity of the world-picture offered us, but denouncing it. And when hell is denounced from within, it ceases to be hell.”

In this spirit, how both Refaat and Ghassan chose to live their short lives should be seen as an unyielding denunciation of the hell that Zionism has imposed on not only the Palestinians, but also on countless Lebanese, Syrians, Egyptians and others in the region into which it has temporarily implanted itself.

All of us who had the privilege to come to know Refaat – whether from afar thanks to the internet and social media, or more intimately than that – must honor that legacy. We cry and we mourn, but we do not despair or give in.

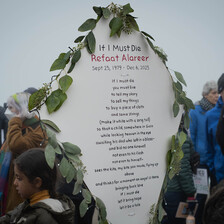

“If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story …

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale.”

Refaat’s poetic directions to us were clear.

I have a dream, one that I have never said out loud or written until this moment, to visit a liberated Gaza and look out at the Mediterranean Sea from a seaside café.

A sea in which Israeli warships, those harbingers of death, no longer lurk menacingly on the horizon. They would instead be a memory from a dark time that has now ended. If that dream comes true, looking out at the sea, I will think of Refaat, the teacher of Gaza, and thank him for all that he has done and taught us, for the profound legacy that his martyrdom left behind.

Louis Allday is a writer, editor and historian.