The Electronic Intifada London 29 December 2012

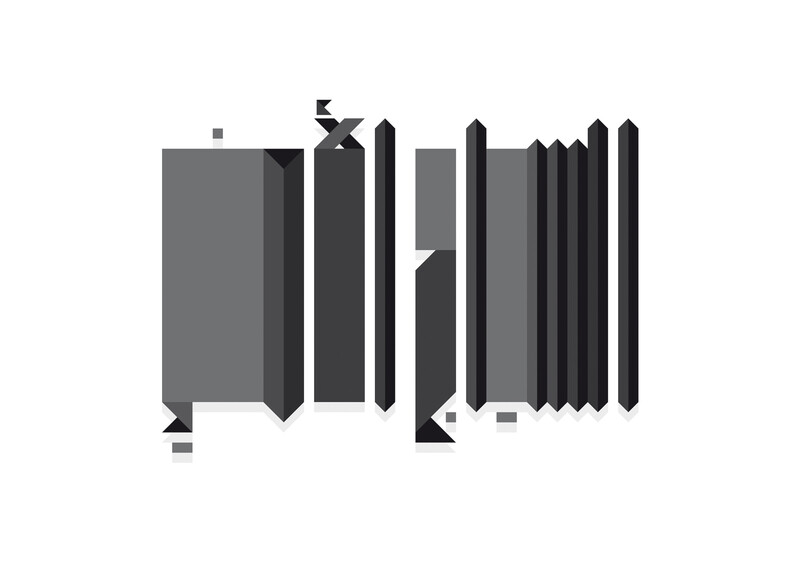

“Palestine” by Muiz (image courtesy of the artist)

“The creative Palestinian must create his flexible margin between the patriotic, the political, the daily, the cultural and the literary. But what am I to do? … Will I be able to write a book of love when color falls on the ground in autumn?”

The Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish asked this question in his 1988 essay “Before I Write My Resignation.” It is a question which has struck artists the world over, but one which came especially to the fore in London’s recent Nour Festival, a celebration of North African and Middle Eastern culture. The theme was played out by its selection of Palestinian artists, performing across a rich literary, artistic and musical program.

The festival’s writer-in-resident, the British-Palestinian Selma Dabbagh, tackled the issue head-on in her series of lectures and workshops entitled “Who Are You To Write That?” which focused on the relationship between politics and literary aesthetics. She explored the expectations placed upon writers to work within certain fields, challenging notions of the writer’s “role” and literature’s function in a political context.

Recurring doubt

Using her own work as a blueprint for analysis, she raised issues of place, identity and the role of perspective in writing, in which doubt was a recurring motif. “The voices told me that I would not be able to communicate a complex political situation in a fictional work, that it was impossible to … create a sense of pace and speed when the atmosphere and history were extraordinarily dense” she said of her most recent novel Out of It, a narrative which connects Gaza, London and the Gulf. Yet this persistent questioning is surely what allowed her to carve out such a raw and honest novel.

Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan, who gave a reading from his new collection Like a Straw Bird It Follows Me, reiterated the necessity of questioning through literature. His work, haunting and compelling, is testimony to the power of literary abstraction.

Speaking about the series of metamorphosing figures which slip silently in and out of his poems, he said: “These ghostly hesitations stem from the idea that it is not the duty of the poet to provide answers; it’s his role to produce questions. And I think that the question, on one level, is an answer, but absolute answers are not the duty of the poet.”

If the role of an artist is to produce questions, then the very representation of Palestine across time and place should itself be questioned and is crucial to understanding the political realities which it in turn shapes. The Nour Festival brought this to light with artistic representations swaying from the “objective reality” discussed in William Holman-Hunt: A Pre-Raphaelite in Jerusalem (a talk focused on a nineteenth century painter); to the contemporary, explored in The Original Arab Spring – Palestine Rising, an exhibition showcasing works inspired by the current political landscape.

”Al-Siaaj al-Amani” (The Security Fence) by Muiz (image courtesy of the artist)

“All art is political”

The group Febrik’s innovative exhibition The Watchtower of Happiness and Other Landscapes of Occupation transformed the gallery in London’s Mosaic Rooms into a reconstruction of the West Bank, exploring issues of the right to public space in the highly polarized context of the Israeli occupation, enabling London’s public to bear witness to the methods of occupation through its interactive installations.

For this writer, the most aesthetically compelling contribution to the festival was visual communicator Muiz’s photo-textual-graphic exhibition, Nuclear Nuqta. His work explores the structuring of our reality through visual language, at the semantic and semiotic level. Building on the principles of Arabic calligraphy, and Islamic geometry and philosophy, the pieces reflect the geo-political structuring of the modern Middle East.

“Palestine,” an arrangement of geometric shapes which individually correspond to the letters of the Arabic and English words, reflects Palestine’s disjointed identity and fractured landscape. The patterns simultaneously spell out poignant motifs in Palestine’s narrative, with symbols reminiscent of traditional Palestinian embroidery and images of mountains, olives and cypress trees identifiable throughout the text.

In “Al-Siaaj al-Amani” (The Security Fence) Muiz spells out the Arabic words with black and grey blocks compressed and stretched across the page, the lettering of the definite article suggesting a stretch of barbed wire and the letter alif dominating the page in the guise of a watch-tower. The piece highlights the abuse of language by the Israeli occupation.

“Nakba” (Catastrophe) commemorates the 64th anniversary of the expulsion of Palestinians from their land. A single line of white tally marks — perhaps a fence, a field of graves, or the stumps of vandalized olive trees — stretches across a plain black background, exposing the devastation of the natural landscape. The unfinished tally marks of the last four years leave a stark ellipses-like reminder of the ongoing nature of this brutal narrative.

Perhaps it is such nuanced abstractions which provide this “flexible margin” Darwish spoke of, “between the patriotic, the political and the cultural.” After all, as Muiz puts it in the festival program, “all art is political – because those that create art are governed by it.”

Brutal influences

Alhmad al-Khatib (image courtesy of Nour Festival)

The Nour Festival’s musical program further illuminated this link between art and politics.

Oud player Ahmad al-Khatib and percussionist Youssef Hbeisch performed material from their acclaimed album Sabil, before being joined by world famous classical guitarist John Williams. Their repertoire included “‘Urs” (Wedding), an exhilarating adaption of a traditional Palestinian folk melody; “Flotilla” in commemoration of the symbolic attempt to break the siege of Gaza in 2009; and “Maqam for Gaza,” a reworking of the classical melodic form inspired by the effects of Operation Cast Lead, Israel’s attack on Gaza in late 2008 and early 2009.

“Sada’” (Echo) has equally brutal influences. Written in 2002 during Israel’s Operation Defensive Shield, it was described by al-Khatib as the “grey spring” when West Bank “Palestinians were kept under curfew for thirty-three days,” turning it into a “ghost city.”

The duo composed this haunting piece while holed up in a flat throughout the siege: the swirl of Hbeisch’s bendir (traditional wide drum) imitating the helicopter’s wail, and the dense knocks on its skin echoing like endless bomb blasts. At times mournfully, at others with stoic rejuvenation, a melody emerges from al-Khatib’s oud, overwhelming the beat of the blasting drum. It is a composition of humanity’s creative triumph over such harrowing hardship.

Music and culture do not simply transport such narratives, they also help nurture a vital sense of hope. As al-Khatib said, “I hope one day this hall will be full of children from Gaza playing their music to us all.”

Lauren Pyott is a freelance writer and translator of Arabic, specializing in Arabic literary translation. She has spent a number of years living in Palestine and is now based in Edinburgh. Her website is laurenpyott.wordpress.com.

Comments

Nuclear Nuqta

Permalink Uri Horesh replied on

I visited the Nuclear Nuqta exhibit twice during its run in London and had lengthy conversations with its creator, Muiz. I myself am a linguist by training, specializing in the study of sociolinguistic variation in Arabic dialects.

I found Muiz's creations extremely inspiring and intelligent, and while he confessed to me that he had no formal linguistic education, the "fonts" he had formed for the exhibition followed meticulous patterns of linguistic logic, which would bring pride to many professional language planners worldwide.

My gut reaction to one of his more abstract works was to call it a "Rosetta Stone," because similar to the Rosetta Stone that led to the decipherment of the hieroglyphics of ancient Egypt, Muiz's equivalent could serve as a roadmap to deciphering several others of his original works of contemporary Arabic calligraphy.

This show really had it all: a great deal of respect for the deep tradition of Arabic calligraphy, a daring collaboration with modern Western photography and other forms of art, bold (and subtle) political statements, and an innovative edge, rendering calligraphy anything but obsolete.

I am extremely glad to have met Muiz at his exhibit and to have befriended him while doing so.