Human Rights Watch 1 October 2003

The United States should deduct the cost of the West Bank separation barrier from U.S. loan guarantees for Israel, Human Rights Watch said today.

In a letter to U.S. President George W. Bush, Human Rights Watch said the barrier’s path and operating arrangements violate the freedom of movement of Palestinians, endangering their access to food, water, education, and medical services. With every mile the barrier cuts into the West Bank, towns, villages, and residents become separated from their lands, crops, services, water, and jobs.

According to the World Bank, some 150,000 Palestinians will be harmed by the first phase of the barrier, which has already been completed. Other phases were likely to affect at least 150,000 more.

“Even in its first phase, the barrier is taking a terrible toll on tens of thousands of people,” said Joe Stork, acting executive director of the Middle East and North Africa division of Human Rights Watch. “President Bush should ensure that the U.S. government does its utmost to prevent these serious violations of international law. Deducting the barrier’s cost from the loan guarantees is an obvious place to start.”

Human Rights Watch recognizes that the Israeli government has a duty to protect its civilians, but notes that Israel is obliged to make sure that its security measures do not violate international human rights and humanitarian law.

Under Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), freedom of movement can be restricted for security reasons - but the restrictions should be limited to what is necessary and proportionate. As defined by the U.N. Human Rights Committee, the authoritative human rights body interpreting the ICCPR, the restrictions should not make movement the exception rather than the norm. The barrier, however, is creating walled-in enclaves confining tens of thousands of people. It will institutionalize a system in which all movement is sharply curtailed except to a handful of permit-holders, and endanger Palestinians’ access to basic services like education and medical care.

The Israeli government has failed to respond publicly to charges that it could adopt less intrusive and less restrictive alternatives to address the security of civilians. In fact, the Israeli State Comptroller published a report in July 2002 strongly criticizing the inadequacy of checkpoint procedures and the lack of army deployment in border areas.

Even if a wall is the least intrusive method available to Israel, as planned the barrier is by definition intrusive because it is being constructed around illegal government sponsored settlements in the West Bank. These intrusions into the West Bank deprive Palestinians of land and are cutting many of them off from services such as education and health care. The Israeli government cannot use security concerns for Israelis living in illegal settlements to justify further illegal changes to occupied territory. Despite the illegality of such changes beyond the Green Line, not one of the competing proposals for the barrier’s route is contiguous with the this line which is the post-1948 demarcation line between Israel and the West Bank.

“Israel has a long history of severe and arbitrary restrictions on movement,” Stork said. “The barrier will institutionalize these restrictions and reinforce the long-term harm done by illegal settlements. That’s why we need strong U.S. intervention, now.”

Background

Human Rights Watch takes no position on the territorial dispute that lies at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, including any changes in land status that might accompany an eventual peace agreement. However, it seeks to ensure that the treatment of people living under Israeli occupation conforms to international legal standards. With this in mind, the organization has impartially and carefully monitored abuses of international human rights and humanitarian law by all parties in the Occupied Territories since 1989.

On April 14, 2002, the Israeli cabinet announced that “fences and other physical obstacles” were to be constructed to prevent Palestinians crossing into Israel. The government announcement, made during Israel’s “Defensive Shield” campaign launched after a spate of suicide attacks against Israeli civilians, said the “buffer zones” were to be created in three areas along the Green Line, the post-1948 demarcation line between Israel and the West Bank.

The “fences” mentioned in that announcement have since become known as the separation barrier, made up of multiple obstacles that will wind through the northern and southern West Bank as well as East Jerusalem. Israeli officials refer to the barrier as the “seam zone.”

Although many public commentators liken the barrier to the fence surrounding the Gaza Strip, the two are not alike. Most important, the separation barrier does not follow the Green Line that divides Israel from the occupied West Bank. The barrier’s division of Palestinian land is what contributes to its harmful humanitarian impact on the Palestinian population.

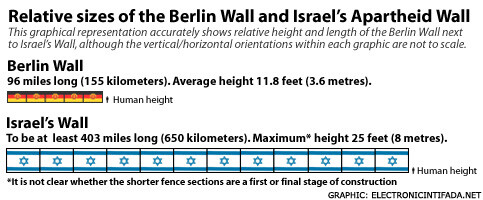

The first phase of the separation barrier was completed at the end of July 2003. It winds approximately 108 miles through the northwestern West Bank. It has resulted in the confiscation of some 2,850 acres of land and carved off some 2 percent of the total area of the West Bank. Two more phases are under construction: one in the northeast of the West Bank, and another in the region of East Jerusalem and Bethlehem. The route of a fourth phase is still under negotiation. Depending on the barrier’s final route, the cost of construction is estimated at up to $1.3 billion.

Although the barrier’s exact elements differ according to location and topography, its core is an electrified fence, 10 feet high, equipped with surveillance cameras and other sensors. It is flanked on either side by six-foot-tall barbed-wire pyramids. Other obstacles include a trench six to eight feet in depth, a military patrol road, and a dirt path to record footprints. The barrier’s total width ranges from 60 to 100 yards.

In at least two locations, Qalqilya and Tulkarem, the barrier takes the shape of a 26-foot-high concrete wall with embedded guard and surveillance towers.

As is common in other locations throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Israeli officials have informed local residents that all movement in the area 50-80 yards adjacent to the barrier will be forbidden. Passage through the barrier will be arranged via gates and larger terminals, although the Israeli authorities have yet to specify the basis on which people will be allowed to cross.

In addition to the separation barrier, Israeli planning maps specify the creation of three “depth barriers”- presumably deep trenches to prevent vehicular traffic-in Jenin and Tulkarem governorates. These are to be built significantly further into the West Bank than the separation barrier’s first phase.

Under customary international humanitarian law, Israel has a positive obligation to ensure the welfare of residents of the West Bank (1907 Hague Regulations on Land Warfare, Article 43). It is also obliged to ensure the passage of emergency medical services, to respect the sick, to allow the passage of foodstuffs and medical goods, and to facilitate education (Fourth Geneva Convention, Articles 16, 20, 25, 50, 55 and 59). Israel is prohibited under customary international law from making permanent changes to the West Bank that do not benefit the local inhabitants (1907 Hague Regulations, Article 55), and from transferring members of its own population into the Occupied Territories (Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 49 (6)).

Israel has also ratified numerous human rights treaties that oblige it to uphold rights to freedom of movement, and access to education, healthcare, work, and water. These include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In August the U.N. Human Rights Committee said that “in the current circumstances, the provisions of the [ICCPR] apply to the benefit of the population of the Occupied Territories, for all conduct by [Israeli] authorities or agents in those territories that affect the enjoyment of rights enshrined in the Covenant and fall within the ambit of State responsibility of Israel under the principles of public international law.”