The Electronic Intifada 1 July 2016

Popular resistance committee leader Murad Shtaiwi’s son was injured in the leg by a rubber-coated bullet fired by Israeli soldiers during a weekly demonstration in Kafr Qaddum.

“We love our land and we will fight.”

So reads a mural painted on a wall in Kafr Qaddum, a Palestinian village in the northern occupied West Bank.

The slogan, adorned with butterflies in the color of the Palestinian flag flying over a barbed wire fence, is the backdrop to the regular demonstrations against the Israeli occupation held in the village since July 2011.

For five years now, villagers have protested every week, demanding access to the main road leading to the city of Nablus and other nearby towns.

Closure

The Israeli military closed that road in 2003 during the height of the second intifada under the pretext of providing security to the approximately 4,000 settlers living in nearby Kedumim.

Kedumim, like all settlements in the West Bank, is illegal under international law, which forbids a power like Israel from transferring its civilian population into the territory it occupies.

The closure forces village residents to take long detours – what was once a short journey of less than four miles to Nablus has tripled in length. This means both lost time and money.

Villagers have died when Israeli forces wouldn’t let ambulances use the main road.

In addition to closing the road, Israel has confiscated more than 10 percent of Kafr Qaddum’s lands for the benefit of its settlements.

More than half of the village’s land is situated in an area designated as under full Israeli control. Residents must obtain Israeli permission to access their farmland, preventing them from tending to their orchards – olives are the main crop in the village – and they are given only a few days to harvest each year.

This is devastating for a village of farmers.

On Fridays, villagers leave the mosque after midday prayer and march towards the roadblock, chanting slogans, throwing stones and burning tires.

There they confront Israeli soldiers, fortified by tanks and militarized bulldozers.

Injuries

More than 80 protesters have been injured by live fire, according to Kafr Qaddum Popular Resistance Committee leader Murad Shtaiwi.

Wael Abdallah, 16, was shot in the thigh by soldiers in early June. The previous day, two brothers, aged 19 and 20, were also injured by live ammunition in a special protest commemorating the Naksa, the Israeli military’s conquest of the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967, Shtaiwi said.

The army also fires bullets made of a metal core and coated with rubber or plastic, as well as tear gas canisters.

Shtaiwi added that soldiers “are starting to throw new kinds of tear gas, much stronger and more powerful, directly towards the protesters and houses.”

Also in the Israeli military’s arsenal against protesters is skunk water, the smell of which was described by The Economist as “raw sewage mixed with putrefying cow’s carcass.” The foul-smelling liquid is sprayed from truck-mounted water cannons during the demonstrations.

A person hit with skunk water must shower and wash their clothes repeatedly to get rid of the stench. Sometimes the liquid is sprayed into houses and yards, where the smell persists for a long time.

“Collective punishment”

The skunk crowd-control weapon, developed in Israel, has been used nearly exclusively on Palestinians, and not Israeli protesters.

The Israeli human rights group B’Tselem has “serious suspicions that the Skunk is used as a collective punitive measure against residents of villages where regular weekly demonstrations are held near the village’s built-up areas.”

But these measures don’t deter the protesters.

“We defend our right to peacefully use the same road our grandparents used. Israel stole that right from us and gave it to the settlers. This road was here before Israel existed and it’s our only connection to major cities,” explained a teacher who participated in a recent demonstration.

“For that reason, we’ll never give up.”

Patricia de Blas is a freelance journalist and photographer from Spain whose work focuses on human rights and development issues. She can be followed on Twitter and Flickr.

Youths prepare to throw stones at Israeli soldiers while journalists look on during a weekly protest in Kafr Qaddum.

A youth wears a mask to protect himself from the tear gas and smoke from burning tires.

Youths try to ignite an unexploded tear gas canister and throw it back towards the Israeli soldiers.

Inside an ambulance that is present at every demonstration, a medic with the Palestine Red Crescent Society treats a man who has been injured in a tear gas canister explosion.

A villager shows a wound caused by a rubber-coated bullet during a previous protest. He needed stitches.

Journalists film Israeli soldiers as they spray skunk water during a demonstration.

Men carry tires to burn them at the beginning of a road closed by the military.

Popular resistance committee coordinator Murad Shtaiwi holds an unexploded tear gas canister fired by Israeli soldiers at protesters.

An iron gate prevents vehicles from entering the settlement of Kedumim, seen in the background, from the main Kafr Qaddum road, which Palestinians are not able to access.

A sculpture next to the checkpoint at the entrance to the Israeli settlement of Kedumim. A young woman in the settlement, who refused to give her name, said that residents of Kedumim are aware of the protests in Kafr Qaddum. ”We can see the black smoke and smell the burning tires. They do it every week. It’s annoying,” she complained. “But the army controls them. We feel safe.”

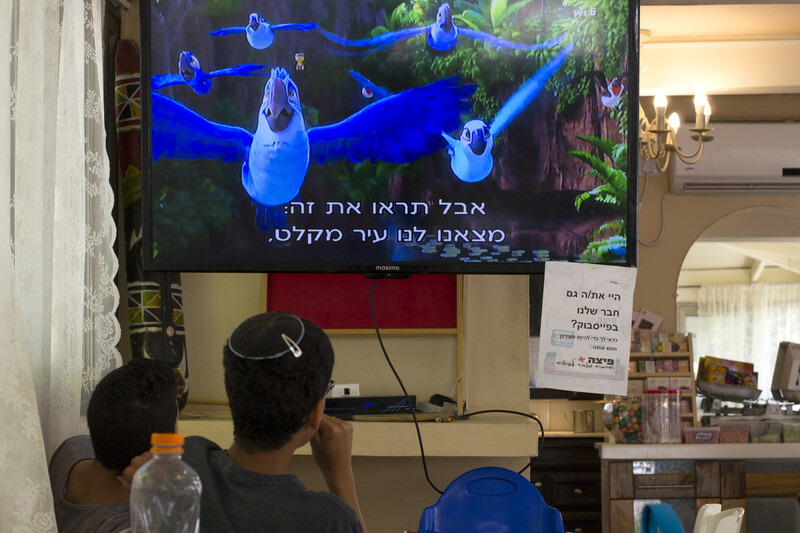

Children watch TV in a café in Kedumim settlement. A waiter at the café alerted soldiers to the presence of this journalist and a colleague. The soldiers took our passports, questioned us and ordered us to leave the settlement.

Looking towards the settlement of Kedumim after one of the demonstrations, a protester takes off his mask and stands next to a pile of burning tires at the beginning of the road that is forbidden for Palestinians.