The Electronic Intifada 13 June 2007

Residents of Budrus sit in front of a bulldozer surrounded by Israeli soldiers trying to prevent the Israeli Army from uprooting olive trees and confiscating more land from the village . (Peace and Love Center)

This year marks the 59th anniversary of the dismemberment of Palestine, otherwise known as the establishment of the state of Israel, and the 40th anniversary of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights. Israel and the western world have imposed sanctions on the Palestinians in the occupied territories, the majority of whom now live below the poverty level; and Israel in collaboration with willing Palestinian lackeys continues its savage assault ostensibly on members of Hamas but in reality on all Palestinians who reject the shabby future assigned to them in the Oslo agreement.

The people of Budrus, a village (population 1,300) about 12 kilometers northwest of Ramallah and no more than 3 kilometers from the green line, teach us that Palestinian fate is not carved in stone; the outcome to the Israel-Palestine struggle is not a foregone conclusion. After the 1948 war, Israel confiscated about 80 percent of the land area of Budrus, leaving less than 5,000 dunums, and later established a military training base. Despite the provocation of the base on village lands, not a single shot was ever fired by the villagers, and not a single suicide bomber ever emerged from the village. Then in 2004 Israeli bulldozers arrived to start work on a wall that, when completed, is expected to extend for about 650 kilometers; it had begun in the Jenin area in the northern West Bank in 2003, jutting well into the West Bank and encircling Qalqilya as it snaked along a southwesterly course. And Budrus brought the bulldozers to a standstill.

The story of Budrus is noteworthy because it reminds us that unarmed people are not powerless. Confronted with an Israeli plan to confiscate 1,000 dunums of village lands to erect a wall that would ultimately enclose area villages in a canton, Budrus residents put their bodies in front of the bulldozers that came to raze their farmlands. Unarmed, and abandoned to their fate by the increasingly useless and indifferent Palestinian Authority, the villagers quickly realized that the wall would stifle the area and make their lives unsustainable. They resisted the Israeli juggernaut with their bodies and temporarily stopped it in its tracks. The villagers paid a high price — the Israeli occupation forces conducted mass arrests and inflicted numerous injuries with live ammunition — and despite a legal victory in an Israeli court, ultimately they could not prevent the 3,500-meter wall from being built. But they did manage to change its course, and in so doing safeguarded some of their own and other village lands. This is an achievement that has eluded local and international activists in Bil’in, who have been holding well-attended and well-publicized (2.4 million hits on Google for “Bil’in” versus 51,600 for “Budrus”) demonstrations at the wall every Friday for at least two years now.

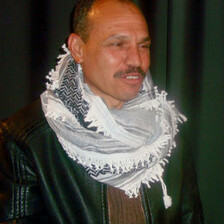

The following interview is a synthesis of two conversations with Abd al-Nasser Marrar, head of the Peace and Love Society and one of the coordinators of the popular resistance committee formed to confront the wall. The wall had not been completed when I met Marrar, then 34 years old, for the first time on 27 August 2005; when we met again less than two years later (24 April 2007), the wall was in place, but it has been the focus of school kids with shears who cut through the coiled wires every chance they get. And although Israel restores the wall that has helped it steal village lands, what has been established is that Palestinians in this small village have not resigned themselves to its presence.

As Marrar noted, “the Berlin Wall fell. The day will come when peace-loving people will wake up. I think there are many Israelis who are working against the wall. If Budrus resists on the eastern side of the wall, let the Israelis resist on the western side. If there really are peace-loving people, that wall will come down. But even without the wall, the occupation is intolerable and cannot be borne.”

A boy holds a bouquet of flowers in front of Israeli border policemen at a demonstration in Budrus. (Peace and Love Center)

The antiwall campaign in Budrus managed to mobilize almost everyone in the village. How would you describe your strategy, and how did it differ from antiwall activities in other areas?

We had been following Israeli plans for the wall from the very beginning, when it was being built in Zububa (in the Jenin district) and in Jayyous. We saw the published plans in the newspapers and saw the area that would be taken from Budrus. Budrus is the gateway to the area. From Budrus the wall would extend to al-Midya, Ni’lin, and Deir Qaddis. We believed that if the resistance to the wall succeeded here, it could set a precedent for the villages that come after Budrus.

We had some contacts with internationals and with the International Solidarity Movement; they had been complaining that popular participation was minimal. So we formed our own popular committee that included representation from all political parties and organizations. This, I believe, made our efforts successful.

International activists in Budrus insisted that no factional flags be allowed, only Palestinian flags. We told them, look, we appreciate your presence, but you have to accept Hamas flags too, because we consider it an accomplishment to get them to participate in a peaceful act. When they saw that Hamas conformed to the agreement, they relaxed. If we had insisted on Palestinian flags only, it would have meant marginalizing people who are part of the resistance, people we can’t do without.

We started our efforts in November 2003. Our first action occurred when the surveyors came; the second one was a women’s march. Then they marked up the olive trees for uprooting, which prompted another action. From the very beginning, we established that our purpose was to stop the bulldozers and not to clash with the soldiers. And in many of our actions, we managed to stop the bulldozers.

In December 2003, the marches were in the northern part of town, the town’s entrance. If the wall had continued in the original course, it would have destroyed Budrus’s economy, because it would have put an end to the olive trees. The actions started there, and they were fierce. The army was determined to take the land, and the families were desperate to save it. The first march was at 4:30 am. The families got to the property and found the army there. People sat under their trees, even though they were beaten with sticks. The bulldozers couldn’t move that day. This went on for a week. The courts stopped activity on the wall for 2 weeks. These two weeks changed the course of the wall, [bringing it closer] to the 1948 line. They started to work on the western side. So the same thing happened; the lands they were threatening to take were all olive tree groves, like the northern side. About 300 people were injured with rubber bullets or tear gas inhalation in the protests; about 30 were jailed. Often the soldiers got out of our way during the marches; they saw that force was not necessary when they face 100 kids who have neither sticks nor stones.

Our goal was primarily to stop the wall and to prevent it from being built on village lands, and in every action we took, we reached the bulldozers and made them stop. It does no good to clash with soldiers, who remain about 100 meters in front of the wall’s path, because the bulldozers can continue to uproot trees unhindered. In my view, the biggest mistake made by Bi’lin was that they clash with the soldiers, who stop them from reaching the wall. The wall remains intact, and its course has never changed.

Unlike other villages that resisted the wall, in Budrus our local committee set the parameters and assumed responsibility for resistance activities. In every march in Budrus, about 99 percent of the residents participate. Moreover, we did not have a specific day of the week for our actions. It was a daily thing. Any day the bulldozers appeared, we had some type of action to oppose them. This meant that people’s lives came to a standstill; employees lost work time, housework didn’t get done. This was an unusual characteristic, the daily activities. Now we see [in other places] that activities take place on Fridays only. Yet Fridays and Saturdays, Israelis are off, so no actual work on the wall takes places on those days. So even if you make it to the wall on those days, you don’t accomplish anything.

In Budrus, female participation was several times more than men’s. People describe rural and peasant women as being conservative and unwilling to leave their homes, but what I saw was exactly the opposite. All they need is someone to encourage their participation. In the first march that was called for, I went to the mosque loudspeaker and announced a march of women and asked that women join, and I didn’t notice a single woman who was absent. No one objected to my call; on the contrary, the women who participated were convinced that they were doing the right thing. We have photos of the first demos here, and it was the women who were stopping the bulldozers. And this happened more than once in Budrus, and they succeeded in getting to the bulldozers before the men did. They were lying down in front of the bulldozers. I haven’t seen similar participation by women in any other location.

We agreed in advance that no one who got arrested would post the 5,000 shekels (roughly $1,200) required for bail. We decided that if we opened the door to this, there would be no end in sight. We insisted on this even though the international activists were prepared to handle this. I was imprisoned for five months as a result of my activities, and about 30 others from here have been jailed. To post bail, you have to go to court, which gives legal sanction to the whole thing, and we didn’t accept that. When I went to court, the charges against me included things like receiving foreigners and inciting people with a loudspeaker. I can’t deny this; whoever comes to town, I am going to bring them to my home.

At every march, more than 50 people were injured, hit by rubber bullets, or tear gas, or beaten with clubs. This was daily, the number of injuries was unreal. We managed to stop the bulldozers more than once. Every march we’ve ever had in Budrus has managed to reach the bulldozers; we didn’t interact with the soldiers.

So you consider your resistance to be successful, even though you weren’t able to stop the wall from being built?

We were very successful. We were able to prevent [the confiscation of] 95 percent of the land that had been slated for expropriation. All of this came with a price that was not trivial — many villagers were arrested and wounded, but in the end we managed to safeguard no less than 1,000 dunums of village lands, and they are planted with olive trees. Changing the route in Budrus may have spared Ni’lin about 2,000 dunums; al-Midya also benefited.

We involved all sectors in the village resistance to the wall — women played an active role, and so did the children, young people and old, everyone participated. The factions were involved too.

How do you get people not to resign themselves to the fact of the wall, since it is in place, a done deal?

People still oppose the wall; that hasn’t changed. Activity levels differ, of course. On Land Day, March 30, the entire village turned out, and we marched to the wall gate. The occupation forces interact with Budrus differently; they want to stop our activities any way they can. They shoot at us with live fire and dumdum bullets, and recently five people were injured. The Israelis distribute leaflets threatening death and imprisonment, things like that. Nevertheless the resistance to the wall remains. In fact, it is impossible to stop it. No one can control it because the occupation refuses to budge. I can’t stop a child or anyone else from opposing the occupation.

The wall here consists of three segments. The kids brought down a main segment, consisting of a coiled wire. The Israelis come and fix it; within a week it is back in place. With every action we take, part of the wall is brought down. On Fridays, you find 90 percent of the children are assembled. Everyone is doing something, some have shears and they are cutting away at the wires. A child was injured here beyond the wall; he cut the wire and crossed beyond the barrier. He was hit with five bullets.

So the wall is just one more symbol of the occupation. It would be hard to convince people that this is a fact they should accept. We are provoked daily, the army is always around and comes to our homes daily, even when no one goes to the wall.

How has the wall affected the people of Budrus?

In any house you go to in Budrus, you will find at least one person who has been injured, one imprisoned. And if you want to compare Budrus to other Palestinian villages, you will find higher percentages in Budrus than elsewhere in Palestine. In 2007, 75 people were arrested in one day [and were given sentences or detention orders] for periods of time ranging from 6 months to 10 years — 75 from a village with a population of 1,300 … arrested in a single day. Thirty were arrested in activities related to the wall, most of them children under age 18. About 30 have been injured with live ammunition. Probably about 1,000 injuries with rubber bullets and tear gas. So every person in Budrus has been injured by the occupation. Maybe that’s part of the reason that residents have so much solidarity with one another.

In my estimation, the wall has created psychological turbulence among Budrus residents, although the actual land area expropriated for it is smaller than in other areas. Here the wall is a coiled wire, but it feels like a structure that denies us air to breathe. With time all people will revolt against it. But we have to know how to aim our compass correctly.

The wall is adjacent to the elementary school. How is it affecting the students?

In school, the kids are afraid and worried. The guards at the wall use tear gas even at a distance. If a kid yells in the direction of the wall, the response is immediate. They try to create an unnatural psychological state. This has been constant, ever since they began the wall here. The policy of the occupation forces hasn’t changed.

The children’s school is no longer a school. The window panes are broken, the classrooms are decrepit. The wall harms the kids’ psyches, it hurts our agriculture, it is bad in every way.

How do you think actions in Budrus affected other areas? You say that the wall moved to Deir Qaddis after Budrus. Was there any coordination between people in these towns?

Yes, there was coordination. In the Ramallah area, Budrus was the first town affected by the wall, and it changed things 180 degrees. A popular committee was formed in Budrus, and then a more regional committee was also formed, and it adopted the Budrus approach. The entire area participated with Budrus and everyone learned from that experience. I have already mentioned that the change in the wall’s path brought about by resistance in Budrus saved some of the land of Ni’lin and al-Midya. Deir Qaddis followed exactly the Budrus model. The only difference is that Deir Qaddis has an Israeli settlement on village lands. So it is impossible to place the wall behind the settlement. Now there are two lawsuits related to the wall. One was filed by the settlement, and the other by the people of Deir Qaddis. The settlers are claiming that the wall is too close to its lands; they want it moved. And the villagers want the wall off village lands. Thus far, work on the wall has come to a stop.

How do you view the Palestinian Authority’s role in this?

The PA has lapsed in its responsibilities toward all the villages west of Ramallah generally and in fact, in the entire West Bank. Its failure has been abnormal and unnatural. Right now, whatever efforts the PA makes are focused on Bi’lin. I don’t see the PA’s media outlets mentioning anything other than Bi’lin. There have been some very difficult humanitarian cases, worse than Bi’lin, that are not mentioned in the media. With all due respect to Bi’lin and the example they set, it is not right to marginalize all other areas and limit the wall to a single focus area.

The PA has to aim its compass correctly, decide how to act; our people have to know how to act. We are an unarmed population. If we want to work correctly, we should think, how many are we, 3 or 4 million? And how many are armed, 4-5,000? You have 3.5 million that you can enlist in nonviolent resistance, popular work, and see what they can accomplish.

Entire villages here are marginalized. None of the PA’s money goes to the areas damaged by the wall.

Not a single PA official came to Budrus when the wall was being constructed. It wasn’t until Budrus started a march to the Council of Ministers that we were able to talk to an official. And he acted as though he was doing us a favor by talking to us or holding a press conference. Frankly, the PA just doesn’t have the interest. The PA didn’t help at all, not a single official did the simplest thing, like donate some banners. At the same time, they come to you and say, we will bring you projects. We don’t want their projects, and anyway, these projects aren’t coming from them. They get international grants, so they aren’t giving me charity. And anyway, the land is gone, so where are they going to put the project?

[Before the elections, we] went to a huge rally in Bi’lin, and there were many members there from the Legislative Council holding signs for candidates; they knew there would be cameras. Even in Friday prayers they were smirking at each other. I am sure that had there been no legislative council and local elections approaching, we wouldn’t have seen a single one of them. For two years, we haven’t seen one of them assume responsibility for the treatment of a single injured person. A ministry for the wall was created, but it has no presence and has done nothing at all. Ask the wall minister about Budrus or Zububa, he doesn’t know them, he’s never been there. The best thing the PA can do if it really wants to work is to use the popular struggle.

I was arrested with a member of the Swedish parliament. The next day, a parliamentary representative was here and so was the Swedish consul. We had many foreign embassies and ambassadors visiting us here. The Swede who was arrested with me is now forbidden to come here for the next 14 years.

Has the wall affected mobility between villages? Are people leaving this area as a result?

Our mobility has been affected by the settlements, not so much the wall; this is part of the plan for the eastern part of the area. The whole area is going to be in a canton. This is an Israeli plan that has not yet been implemented. It will connect Rantis, pass through Shuqba, Ni’lin, and Kiryat Shevar settlement. That will mean that Shuqba, Shibteen, Budrus, and Ni’lin, and al-Midya will be within a canton. There will be a tunnel from Ni’lin to Deir Qaddis. We don’t know when they will start this, but they are ready to begin. There has been some discussion about forming a committee to oppose this plan. We are working on this.

For people who do construction work in Ramallah, about 7-10 families moved there, just because of the lengthy commute. About 90 percent of those who had worked in Israel are not permitted to work there any more, but some work in Israel illegally, and they stay away for a week or two at a time.

The situation in Ramallah seems abnormally normal to me, because the city is isolated from what is happening elsewhere.

Of course it is abnormal. When villages are cut off from the city, what becomes of it? What creates life in the cities other than the surrounding villages and towns? Cities are nourished by the life in the surrounding villages. The economy and jobs in cities are spurred by the villages. The movement of people from the villages to the cities is what creates life in the cities. When the villages are cut off from Ramallah, what happens to it? It diminishes.

How do you keep your spirits up? What keeps you going?

Our affection for and solidarity with one another. When we turn out for an action, we feel that we are accomplishing something. We might be able to move the wall 5 or 10 meters or so, but you feel that something can be done about it. If Ramallah were to march on to Budrus, I am sure that not a segment of the wall would remain between Rantis and al-Midya. If we work seriously, I am sure that nothing would remain. The occupation can’t line up soldiers between Rantis and al-Midya. We had a march that gathered at one gate (western side), covered by al-Jazeera and al-Arabiya and other agencies, and people were taking down the wall from the southern end. Nothing is impossible.

The Berlin Wall fell. The day will come when peace-loving people will wake up. I think there are many Israelis who are working against the wall. If Budrus resists on the eastern side of the wall, let the Israelis resist on the western side. If there really are peace-loving people, that wall will come down. It just needs some planning and some determination.

Ida Audeh is a Palestinian from the West Bank who works as a technical editor in Boulder, CO. She is the author of the five-part series, “Living in the Shadow of the Wall,” published by Electronic Intifada on 16 November 2003; “Picking Olives and Removing Roadblocks as Acts of Resistance: An Interview with Ghassan Andoni,” Counterpunch, 28 October 2002; and “Narratives of Siege: Eyewitness Testimonies from Jenin, Bethlehem, and Nablus,” Journal of Palestine Studies, no. 124 (Summer 2002). She can be reached at idaaudeh AT yahoo DOT com.

Related Links