United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 28 September 2006

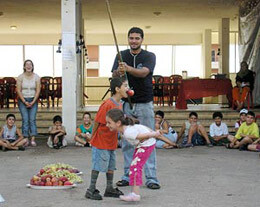

Children still displaced by the war take part in a Beirut summer school sponsored by UNHCR. (UNHCR/A.Rehrl)

Before the five-week war, the southern suburb’s 275,000 permanent residents - mostly Shia Muslims and poor - lived cheek by jowl with migrants and Iraqi refugees and asylum seekers. They have since been joined by hundreds of displaced Lebanese, whose houses in neighbouring districts were destroyed by Israeli fire or who fled from the south to stay with families in the capital until it is safe to return. Uncertainty among the internally displaced people (IDPs) is high.

UNHCR is reaching out to these folk - and other IDPs around Lebanon - with the help of social development centres. The displaced were a bit wary at first, but they have come to trust the refugee agency and appreciate the distribution of UNHCR relief items. Local social workers now come regularly to discuss needs and issues of concern with UNHCR staff.

“Whenever UNHCR comes, we are well received,” said Tiziana Clerico, community services officer for UNHCR in the southern city of Sidon. “People in the villages really appreciate what we have done for them.”

Ali Bazzi, director of the social development centre in Hai Al Sullam, noted that most people whose houses had been destroyed had received money from Lebanese groups. “But they don’t spend it for rent, they live on it now,” Bazzi said, adding: “They will probably spend the winter here in Beirut, until they know what happens next.”

Aside from accommodation, money is a big concern for most IDPs - many farmers, for instance, lost their harvests because of the war and face continued danger from unexploded ordnance littering their fields. This will affect their livelihood.

In Hai Al Sullam, Bazzi is also worried about indiscipline among children who have missed their summer vacation and lack order in their lives. Young boys playing on the district’s narrow streets, fight and shout instead of playing their once habitual game of football. Children have become much more aggressive.

“We have to do something about it,” Bazzi said. “These children not only deserve some recreation or entertainment, they also need to be educated in discipline. Right now we have 10 to 15 children living in a house - this creates tensions. And if they are left on the street, they may turn into criminals.”

With help from UNHCR, he organised a 10-day summer school for 100 children aged between nine and 14. The refugee agency provided tents, mattresses, blankets, lanterns and kitchen sets for the camp, which was held in the playground of a nearby school and ended last Sunday.

The children, picked from the poorest and neediest families, were kept busy with a host of activities. There was even a psychologist on hand to help those with emotional problems. “Many of our children need psycho-social care and their parents need some relief,” Bazzi explained.

But while Bazzi’s social development centre is providing an invaluable service, the demands for help are straining its resources. “We have around 175 people coming every day to our centre to ask for some kind of assistance,” he said. “Some come for health assistance, others are interested in vocational training, others need support for their children. We have limits and I cannot take care of everybody.”

With the spotlight now elsewhere in the world, some groups are starting to feel they have been forgotten. This is especially true of the vulnerable, of older people, those with handicaps, and widows, who find it more difficult to get the assistance they need.

But without the social development centres in places like Hai Ul Sallam, Lebanon’s remaining displaced would have an even harder time and UNHCR, other UN agencies and non-governmental organisations would find it more difficult to distribute relief items and conduct needs assessments.

And Lebanon’s displaced will clearly need help and continued support from overseas for some time to come.

Related Links