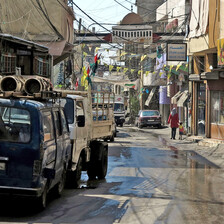

Nahr al-Bared refugee camp 22 October 2008

A view of a large portion of the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp that was destroyed in 2007 and still remains off limits to its residents, October 2008. (Ray Smith)

One year has passed since the first Palestinians were allowed to return to the outskirts of the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp, destroyed by the Lebanese army during three months of fighting in the summer of 2007 with Fatah al-Islam, a small Islamist militant group. Meanwhile, up to 15,000 people have resettled in the camp. Many of them are still waiting to freely access their destroyed homes, as the Lebanese army still exclusively controls the “old camp” in the core of Nahr al-Bared, as well as parts of the “new camp” on the outskirts.

Abu Khalil, owner of a small bookstore at the former main street of the camp, says that he spent $3,000 on infrastructure and $10,000 on merchandise to reopen his shop after the war. However, he’s struggling with low numbers of customers. He explains that before the war, not only Palestinians from the camp came to his bookstore, but also Palestinian refugees from nearby Beddawi camp and Lebanese from the northern region of Akkar, “I used to sell to 100,000 people, these days I only sell to the 13,000 who are present in Nahr al-Bared. Now, I’m essentially besieged. The Lebanese army should allow people to freely enter and leave the camp!”

Nahr al-Bared refugee camp was a thriving economic center in northern Lebanon, nestled between the city of Tripoli and the Syrian border along the coastal highway that joins the north to Beirut. Nidal, a political leader in the camp, explains that “It was well-known that in Nahr al-Bared you could buy goods on credit. Lebanese shops don’t work this way. Also, things here were cheaper and people imported directly from foreign countries.” Unlike other Palestinian camps in Lebanon, Nahr al-Bared was for many years accessible without restrictions. Only a few months before the Lebanese army launched its devastating attack against the camp, checkpoints were erected on the camp’s perimeter. While these checkpoints inflicted damage on the local economy, they were apparently unable to stop massive amounts of weapons and ammunition from entering the camp and reaching the militants of Fatah al-Islam.

A widely held belief among Palestinians from Nahr al-Bared is that the camp’s success was the real reason it was destroyed by the Lebanese army. However, Nidal warns that one should not overestimate economic factors, stating, “Maybe they were partly motivating the destruction, but surely there were other reasons — political ones. These are related to the Palestinian right of return to their homeland and to its opposite, to their resettlement in Lebanon.” He recalls Lebanese Prime Minister Fouad Siniora’s statement at the time that he intended to make Nahr al-Bared a “model camp” for all Palestinians in Lebanon.

In spite of the promises by Lebanese leaders to rebuild the camp, many refugees from the old camp of Nahr al-Bared are skeptical that this will actually happen. Abu Khalil complains that they were told many empty promises: “They said they’d start in the beginning of September. Then on 15 September, then on 20 September. Now they say they’ll start after the Eid [holiday at the end of Ramadan]. God knows how long it will take again after the Eid.”

The initial reconstruction plan by the Lebanese government and the UN agency for Palestine refugees, UNRWA, set the 15 August 2008 as the date for the beginning of the staged reconstruction process. However, until now nothing has been done and the reasons for this are unclear. Recently, camp residents were told that the bulldozers, trucks and other machines weren’t ready. On 6 October they were told that the army needed time to train the construction workers regarding unexploded ammunition. On 10 October, some bulldozers finally appeared in the old camp and appeared to be widening and preparing the streets for more construction machines and trucks to enter.

Those families currently living in temporary housing, known as “the barracks,” are losing their patience. A resident of the barracks on the camp’s northern end complains about the miserable housing conditions and says, “They just brought us here in order to silence us. That’s what the barracks and the aid packages are for. But we insist on returning to the old camp as soon as possible.” Although, there is hardly any visible political activism inside Nahr al-Bared regarding return to the old camp, on 1 October, the first day of the Eid, residents successfully broke through the soldiers lines to visit the graves of their relatives. The army had intended to allow visitors to enter the severely damaged old graveyard at the old camp’s southern entrance in small groups and only after security checks. However, residents started shouting at the soldiers and eventually broke through the checkpoint to reach the cemetery.

While Nidal is convinced that the camp will be rebuilt, instead he asks, “Who’s going to administer the camp? The Popular Committee of Nahr al-Bared or the Lebanese authorities through the Internal Security Forces?” He fears the implementation of Siniora’s plan will be detrimental to Palestinian self-governance and keep the camp under Lebanese control.

Residents have already started to avoid discussing political topics and issues regarding developments inside the camp for fear of an increased number of spies and collaborators working for the Lebanese secret services. The suspected recruitment of collaborators also seems to have a negative impact on the unity of the refugees in Nahr al-Bared who appear to be losing trust for other residents in the camp. Such developments indicate — in contrast to the promises made by the Lebanese government and UNRWA — a cloudy future for Nahr al-Bared.

Ray Smith is an activist with the anarchist video collective a-films. In a workshop in Nahr al-Bared camp in October 2008, the collective produced their latest short movie on the economy of the camp and about its reconstruction.

Related Links