The Electronic Intifada 12 June 2017

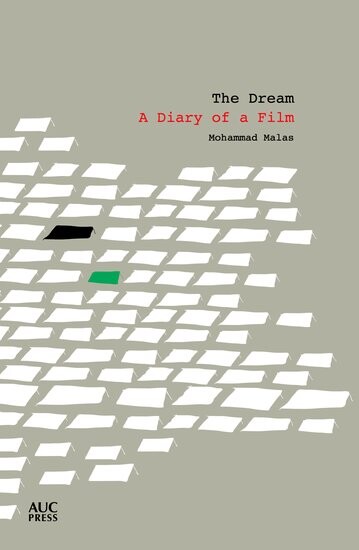

The Dream: A Diary of a Film, Mohammad Malas, The American University in Cairo Press (2016)

Mohammad Malas’ book, The Dream: A Diary of a Film, was not, when it was written, meant to be a time capsule, documenting the Palestinian refugee camps of Lebanon at a disastrous turning point.

Malas, a Syrian filmmaker, traveled to Lebanon in the early 1980s to film a documentary about Palestinians in refugee camps. It was on location that he decided to devote a film to dreams.

Malas spent more than a year interviewing hundreds of Palestinian refugees about their dreams for use in his film. But then – after he had returned to Syria for editing – came the massacres at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in 1982. Many of his subjects resided in Shatila.

Malas halted work on the film, and it was was not fully completed until 1987. Titled The Dream, it went on to win first prize at the Cannes International Audiovisual Festival. The first people to see it, Malas explains in his book, were residents of Shatila who saw a reel of the film that had been smuggled into the camp.

While on location, Malas kept a diary in which he recorded the interviews, his thoughts about the interviewees, and musings on creating the film itself. The diary was first published in Arabic in 1991; The Dream: A Diary of a Film is its first English translation.

The context in which these writings were made give Malas’ book a resonance beyond the making of a film. It is a recollection of a community that would suffer the most infamous mass murder of Lebanon’s civil war.

The film is a window into its subjects’ minds. They recall their dreams, where they live, work or do chores. The scenes, however, are somewhat staged. All those who appear on camera had already described their dreams to Malas during the scouting stage and were instructed on their actions in the film.

Since the book is a diary that encompasses Malas’ entire filmmaking process, including scouting, the reader is thus presented with a less-staged portrayal of the interviewees, many of whose stories did not make it into the film.

Otherworldly sadness

At the time Malas was filming, Lebanon was steeped in a critical period of its civil war and the Palestine Liberation Organization was at its peak in the country, a situation that would quickly and dramatically reverse.

A number of interviewees either worked for the Palestine Martyrs Works Society, known as Samed – an industrial group affiliated with the Fatah faction that provided jobs and training in Palestinian refugee camps – or had family who worked for Samed or joined the resistance against Israel.

Many of the dreams in the book recall family who had died in fighting or offer an otherworldly sadness regarding the slaughter witnessed by the dreamers. One young woman explains a dream she had of her deceased brother:

“I was standing. Someone told me, ‘Nizar at the American University – he’s sick, there’s no hope.’ They brought him. He was wrapped in a cloth. They put him on this bed, the bed where I sleep. I looked and saw that he wasn’t dead. I hugged him and kissed him. He was laughing without making a sound.”

Another woman, who commented that she sees “nothing except graves and corpses” at night, says: “Sometimes when I’m eating [in my dreams] I feel that the meat I’m eating comes from a corpse. I see myself crying. I cry because I’m crying. When I wake up from the dream and remember the crying, I start to cry.”

Sometimes the dreams point to the desperation of living in the confines of the camps. One woman’s dream entails being told by a relative that “the visa was issued.” She goes to the airport with her children only to discover that she did not have a visa under her name. She returns home and slams her bag on the floor out of frustration.

The book sheds light on Malas’ artistic process, providing great insight for those interested in his work or filmmaking in general.

Early in the filming stage, he describes a scene in which he films an interviewee named Abu Shaker preparing to sleep. When Abu Shaker crawls into bed and covers himself with a white sheet, he almost appears dead – to the point that his wife, who was observing the filming, begins weeping and screaming at the “omen.”

Malas notes in the book that he wants this to be the final scene in the film.

Richness in text

The behind-the-scenes commentary paired with Malas’ insights – and, in some cases, encounters that can’t be seen in the film – are what breathe richness into the book.

One of the interviewees named Gladys who worked in the Samed workshop recounts a dream in which her father beat her mother. She begins to weep as she describes the dream – right as all of the sewing machines in the workshop where she was being interviewed turn off in unison. The power in the factory fails just as Gladys starts crying.

In another part of the book Malas describes shooting film in a darkroom while the interviewee develops film. The dream being told relates to the death of Gamal Abdel Nasser. The photos being developed would eventually reveal – as Malas had already determined, and while the subject describes Nasser’s death – Arab leaders who had gained power after the Egyptian president’s departure.

The stories capture a particularly disquieting historical moment that ended in harrowing violence. Unexpectedly, the interviews in this book became a memorial, the lives, dreams and frustrations of a people devastated permeating its pages.

Few things are more personal than dreams. In Malas’ book, they form the greatest tribute to those who perished and a trove for those who don’t want to forget.

Marguerite Dabaie is a Palestinian American illustrator and cartoonist based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work can be found at www.mdabaie.com.