All that remains of Netzarim settlement.

After 38 years and 67 days, they were finally gone. They being the Israeli soldiers and settlers of course, that for so long made our lives miserable here in Gaza.

I went to tour the vacated colonies-as a journalist, but also as an ordinary Palestinian. Like thousands of other Palestinians, I was simply curious, and, in the end, giddy, awe-struck, and in absolute disbelief. I got up early, wasting no time after the last of the soldiers left to take a peak at what lay beyond the once fortified colonies, that although only metres away, for Palestinians, may as well have been on a different planet.

It was, simply put, a journey into the surreal. Katrina meets Disney World.

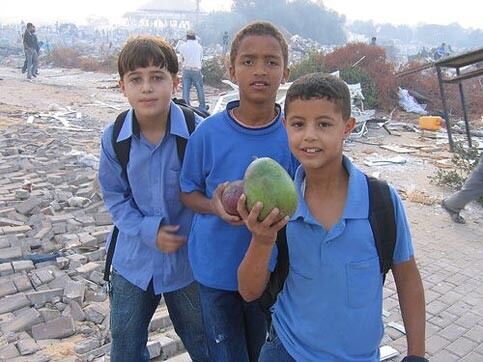

Palestinian boys hold a mango picked off of a tree in the colony of Netzarim, uprooted by Israeli soldiers before they left Gaza.

Some children picked large mangoes off a razed tree, while others took to scavenging for leftover toys and books; some found Jewish skullcaps and wore them while posing, oblivious to the irony, next to Hamas flags. Others tied orange anti-disengagement ribbons to their heads. All were at once elated and dumbfounded, relieved and overwhelmed. And just about everybody wanted a souvenir.

Amidst the curious crowds, a Palestinian photojournalist walked around in a vest stapled with pictures he took of Palestinians killed by Israelis forces not far from Netzarim in years past, including the youngest victim-4-month-old Iman Hijju of Khan Yunis.

“I want them to witness this historic moment with me. I want to also make sure that people never forget them and what they died for,” he said.

A Palestinian photojournalist wears a vest plastered with pictures of Palestinain martyrs killed by Israeli forces throughout the four years of the Intifada so they too could “witness” the momentous occasion, and so people and media touring the settlements would not forget their suffering.

Nearby, a twenty-something Palestinian who lost his leg to Israeli gunfire 4 years ago hobbled around in disbelief, pausing a moment to stare at the now demolished sniper tower from which he was shot.

Inside the former synagogue of Neve Dekalim, built in the shape of a Star of David that was built to purposefully overlook the impoverished and battered Khan Yunis Refugee camp, charred anti-disengagement literature and flyers advertising “tours” to Gush Qatif as “New Zionism plus Torah True Living in Action” were strewn about. “Let us help you to sense the magic being felt daily in this beautiful part of our homeland,” read the flyer.

Young Palestinians refugee boys from Khan Younis take a peak inside the walled in former settlement of Neve Dekalim which overlooks the refugee camp.

Many Palestinian boys, backpacks still on shoulder, skipped school in favor of the exploratory visits to the abandoned colonies that for so long were a source of their grief and misery.

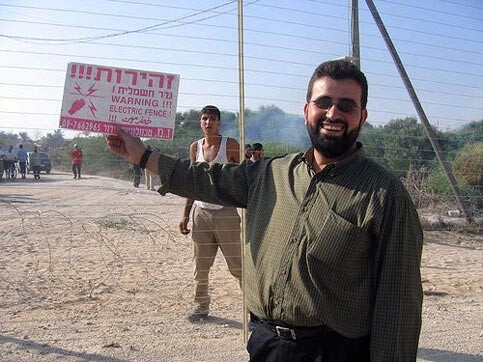

A Palestinian man holds up a sign warning Palestinains to keep away from the electric fence surrounding Kfar Darom.

In the former colony of Kfar Darom, young refugee children from the camp of Dair al-Balah played in an abandoned playground. Palestinian security officers who had been up since 3am for the handover of the settlement lands dozed off under the shade of a large mulberry tree, while young children clamored for a photo opportunity in an abandoned but not yet demolished sniper tower that overlooked a pockmarked UN school.

Palestinians reclaim a former Israeli sniper tower in Kfar Darom.

Further south, Palestinians drove past the Abo Holi checkpoint for the first time in 6 years without having to stop and wait for orders to pass, though a traffic jam ensued as Palestinian forces took down a watchtower that Israeli forces had abandoned but not dismantled.

And in Rafah, I joined thousands of Palestinians who streamed across the once impermeable and deadly wall that divided this border town into two, visiting family and friends they had not seen in decades, standing in the very location where Israeli tanks once nested awaiting orders to pound this battered refugee camp, their tracks still freshly imprinted in the sand. Overhead, a white Israeli drone whirred menacingly, serving as an eerie reminder that Israeli occupation forces were never far behind.

But many Palestinians, while living the historic moment, expressed concerns for the future. Dermatologist Muna al-Farra, who was finally been able to access land her family owns in the Abo Holi junction, said she was worried about the longer-term implications of Gaza being turned into like a large prison.

“It makes me think-what was the struggle for? Just to be able to drive from Gaza city to Rafah?”

Musa al-Ghul, a local community leader of the northern Gaza village of al-Siyafa, which was fenced in and sandwiched between the former colonies of Dugit and Eli Sinai, had similar words of caution. Even a golden palace is still a prison if its occupants can’t get out freely, he said, and, having living as prisoner inside al-Siyafa for 6 years, no one knows that better than him.

“Nothing equals freedom…nothing. Even if you are in a golden palace, and somebody said ‘you can leave at this time, eat at this time’, then you will not enjoy everything. You will feel humiliated and trapped. But even if you are in a tent with freedom of access, it means everything. Freedom is life. Without freedom of movement there is no life.”

Still, Palestinians celebrated. Thousands swarmed the Khan Younis seashore, which for over 6 years had been off limits to them.

Laila’s son Yousuf is absolutely giddy on Gaza’s beach, with a beautiful sunset backdrop.

Young boys surfed on broken refrigerator doors; children ran boisterously around abandoned sea shacks and flew kites; and families took the day off to picnic.

A Palestinian boy fishes on the Khan Younis seashore, formerly inaccsible for over 6 years.

But in the end, al-Farra and al-Ghul’s words of warning reverberated in my head, and I couldn’t help but feel like a small hamster, who was released from the confines of a small, decrepit cage with a vexing obstacle course to maneuver around, to a more spacious, less restrictive one; basking in the elation of its new-found freedom, forgetting, for just a moment, that it was still walled in from all sides.

Laila M. El-Haddad is a journalist based in the Gaza Strip.

Laila and her son Yousuf