Gush Shalom 9 November 2002

WHERE WE WERE WHEN THE GOVERNMENT FELL: A REPORT OF THREE HECTIC DAYS

People gather at the Rabin Memorial on November 2nd. Rabin was assasinated in November 1995 by right wing student, Yigal Amir.

At least, attending this year’s rally — unlike those of the past two years — did not involve the emotional wrench of having to listen to a keynote speaker directly involved in the war against the Palestinians such as PM Ehud Barak in the rally of November 2000 or Dalia Rabin-Pelosof, Deputy Defence Minister in 2001.

In retrospect she herself, the daughter of Yitzchak Rabin, may have felt uncomfortable with it; she resigned from the government a few months later, a step which marked a beginning of internal pressures and grassroots resurgence in the Labor Party, and which finally led to the party ministers’ long-overdue resignation from the Sharon Government.

So, this year’s Rabin Rally, seven years after the murder, however officially touted as “non-partisan”, was in a way the first manifestation of a new political reality. In other times, the enormous sign “We Believe in Peace” over the podium may have been only a cliche or pious wish; in the Israel of November 2002 it was just a bit more: a crowd of about 100,000 mostly young people defying the trend of ‘peace is dead’.

The organizers, meanwhile, had gone to considerable trouble to obscure the identity of Israel’s partner for peace - featuring filmed addresses from King Abdullah of Jordan, President Mubarak of Egypt and Former US President Clinton, while pointedly neglecting to let any Palestinian speak; and the historic handshake between Rabin and Arafat featured only in the stickers distributed in big quantity by Gush Shalom, not in any of the organizers’ posters and ballers.

But there were quite a few moments of dissidence - some on the podium, some in the crowd, quite a few in the interaction between the two: the explicit anti-occupation signs conspicious among the medley of banners and placards visible in the square, “Hashomer Hatzair Youth Movement fights the occupation” and “Get out of the Territories!” and “Refusal to serve the occupation is the true Zionism”; and the swelling applause to actress Anat Gov’s words “The right- wingers try to criminalize us, to put all blame for the country’s woes on the ‘criminals of Oslo’; well, better to be a peace criminal than a war criminal”; Singer Aviv Gefen calling upon “everybody who has had enough of the occupation” to raise their arms and getting a resounding response.

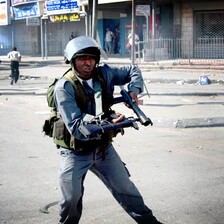

Armed Israeli guard protect a Caterpillar bulldozer clearing Palestinian land. Photo by Sune Segal.

While being enclosed within an enormous wall would make the West Bank even more of a prison camp than it already is, it does not at all automatically lead to Israeli withdrawal. It didn’t in the Gaza Strip, already for years enclosed by a similar construction.

Throughout the rally there were activists circulating among the crowd — the largest gathering of peace camp grassroots supporters anywhere in the year — distributing leaflets on the iniquities and dangers of the Separation Wall. Dozens of others held aloft large banners on which the bricks of a wall were painted with the slogan “The Evil Fence - Ghetto for Palestinians, Disaster for Israelis”. With more than twenty of them held side by side, a quite realistic image of a wall was created in the center of the Square.

Defending the olive trees

Israeli Caterpillar excavator works Falamiya land, with the nearby village of Ta’ayush in the background. Photo by Sune Segal.

So it was, on that early Monday morning, that four representatives of Bat Shalom and Gush Shalom found themselves in a small van, en route to a completely different world lying just half an hour’s drive from Tel Aviv. First crossing the unmarked, but somehow very obvious Green Line; a drive along a main West Bank highway, nowadays reserved for settler use and lined with signs promising “The house of your dreams” at various settlements; then stopping at the entrance to a side-road, closed off from the highway by huge concrete blocks, to prevent Palestinian cars from using it; then a drive in a Palestinian taxi along a winding hilly track from one village to another; then Falami, our destination, a neat village of some 600 inhabitants. A man with a traditional headdress, who turns out to be the mayor, insists on letting us have breakfast in his home.

On a cursory glance, Falami seems a bit better off than many other places in the West Bank. That is because up to now they had enough land - and an irrigation project to make good use of these lands - to live mainly from agriculture. All that is now under immediate threat. We go into a car, and travel through a pastoral landscape. Suddenly, we could here shouts ahead.

A destroyed olive tree. Photo by Sune Segal.

The man with the chainsaw was deft and efficient. First the side branches were lopped off one by one, then the central trunk, and then off to the next tree. It did not take him more than two of three minutes to destroy a tree. He was guarded by eight armed men - four “Border Guards” in khaki; four private security guards in dark blue. With each tree he tackled they speard all around, their rifles pointing outwards. Gradually, we started getting off the road and coming closer.

Verbal admonitions were clearly utterly useless towards this crew. They either ignored them or answered with obscenities. Some of us started running ahead of them, getting to still undamaged trees and holding on to them. The man with the chain-saw was quite angry: “Get off, fucking bastard leftists! I am going to cut off the tree. If you get in the way, that’s your lookout!” He did lop off the outer branches.

A scuffle between the peace activists and the guards. Photo by Sune Segal.

Still, the trunk of an olive tree is exactly the right size to be hugged and held on to with all one’s might… There were some moments of a dialogue of some kind. If he is to be believed, the man with the saw was especially angry because he felt we were trying to deprive him of the first job he got after a long time of unemployment. “And anyway, if I don’t do it, somebody else will”. (An old argument, as was the Border Guards’ “I am just obeying orders”.) After a time, they just seemed to decide to leave us where we were and go on to other trees - which seemed an effective tactic, since there were more trees than activists.

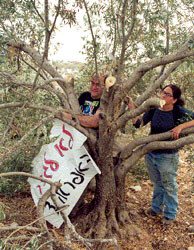

Israeli activists attempt to prevent the destruction of an olive tree. Photo by Sune Segal.

As we learned via cellphone, an official of the special governmental agency charged with creating the wall had arrived, and negotiations were going on. It turned out that the contractor was supposed to cease work pending the arrival of the French Consul on the following day, to discuss the fate of the irrigation project which the French government had built in this village. Anyway, the result of the negotiations was an all-clear. It was possible to come out of the trees. We had saved them, at least for one or two days.

The next day

On the following morning, the village looked quite different. When we arrived (seven Israelis this time) the Falami school children were strung out on parade along the street, having just greeted the village’s important guest on his arrival. The Consul was already inside — one of the East Jerusalem consuls, who are de-facto ambassadors to Palestine. When we got in, the mayor was extolling the French-installed irrigation system: “Our land has become a paradise. We grow everything: apricots and cucumbers and citrus, anything you want. We have good land and the water. Now our people see them taking it all away”.

After the meeting, the consul was taken to see for himself. A procession was formed. The Consul, a good-looking tall man in a neat blue suit asking attentive questions in fluent Arabic, was accompanied by village notables and represantives of Palestinian NGO’s arrived from Nablus and Ramallah, and followed through the main street by a crowd of villagers mixed with internationals and Israelis.

Two young men brought up the rear, one holding aloft the French Tricolor and the other, the Palestinian Black-White-Red-and- Green. From the top of a blockhouse, the Palestinians pointed out the details of the impending destruction: “The wall will pass through that green field, cutting it in half. All the further fields will be lost to us. The hothouses, over there, will be destroyed. The well will remain on the other side. We will have no control over what comes through the pipes.”

The government claims that Palestinian farmers will be allowed to work their fields on the other side. From experience (as when Palestinian farmland was enclosed within a settlement’s perimeter fence, and a similar promise given) the Palestinians are right to be highly sceptical. A representative of the Agricultural Relief Committees spreads a map of the Separation Wall’s entire planned course: “Everywhere, they try to grab the ground water. That is the main consideration, not security. It is an old plan, but now they are actually implementing it”.

From there the procession moves to another sector: the scene of yesterday’s clash at the olive grove, which is inspected by the visiting diplomat. Everything is as it was left on the previous day, the destroyed trees and the undamaged ones - even the strewn pieces of our placards, torn to pieces by the security guards. Then he got into his car and drove off. There was some confusion as to what comes next. The consul was going to have a crucial meeting with the government officials in charge of building the Wall, and take up the issue of the Falami lands. The officials had refused to meet him in the village itself, judging the place “too dangerous” and the meeting was to be held somewhere in the open fields.

While still standing there a movement became visible among the trees of the ravaged olive grove. Soldiers appeared, moving purposefully in a skirmish line, their guns at the ready. We linked arms, preparing to offer passive resistance to an eviction order - but the soldiers moved past, studiously ignoring our presence. We continued standing and waiting - when suddenly the elements intervened, a cloud moved across what had been a scorching sun, and the first thunderstorm and heavy rain of the year found us standing in the open field.

Fortunately, the Palestinians pointed out a nearby cave with a low-ceiling — apparently being used as a sheepfold. For an hour, Palestinians, Israelis and internationals sat huddled together, some dozing, a few turning on squeaking radios. It was there that we heard of the Sharon Government’s fall and the scheduling of new elections. The Italians, who seemed to predominate among the international contingent, started singing an old partisan song; soon the others joined the catchy tune and the clapping.

Gradually, people started drifting out, though the rain had by no means fully abated. The news filtered around: the meeting for which we had waited was taking place a few hundred metres up the track. We moved in that direction, determined to make our presence felt, and encountered the soldiers. “No, no, forbidden. It is security, the French Parliament is here. Security!” shouted a young sergeant.

There we were, blocked in the drenching rain. A short way ahead of us we could make out a square, heavy car, light gray in colour, with a winking yellow strobe light on top. Not far from it, another grey car with the initials T.V. marked largely with white tape. (The reporter of a French network has shown a remarkable devotion to duty, going on to take his footage in the heaviest of rain.) An army jeep pulled up - and got promptly stuck in the mud. All further efforts merely stuck it deeper and deeper. And suddenly everybody — peace protesters, villagers and blocking soldiers alike — burst out laughing, there in the drenching rain.

Epilogue

The consul’s meeting with the officials, on which the Falami vilagers pinned so much hope, ended in failure. The officials’ mandate was limited — or so they said — to discussing “the laying of irrigation pipes under the fence, once it is completed”. For any deviation from the track defined for “the Fence” itself, they refered him to the political echelon, to Sharon personally or the newly-appointed acting Defence Minister Mofaz.

Meanwhile, the army declared the respite over and allowed the contractors to move back in. So, by the time you read this, the olive grove over which we struggled may have been already completely devastated, and the bulldozers may be cutting a swathe of destruction through the beautiful green fields where we walked yesterday.

Veteran Israeli activist Adam Keller is spokesman of Gush Shalom.