Burj al-Barajne Refugee Camp 22 July 2007

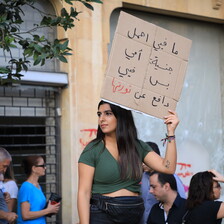

Burj al-Barajne refugee camp, Lebanon. (Dr. Marcy Newman)

Fadia greets me with a warm smile of welcome lighting up her face and takes me to her home in Burj al-Barajne camp, Beirut, where I am to stay for three weeks, trying to help with a summer activity program for some of the children, and to improve the English of her kindergarten teachers. She has an infectious laugh and seems to find much to smile about. As I stay in the camp and learn more of what it means to be a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon I marvel at her strength of character, a common feature of the Palestinian women I have met. One would not guess from her smiles at the pain that lies beneath. Samoud, her daughter, tells me, “We have a story of two women, one of whom has known nothing but bad things in her life but is always smiling and one who has known nothing but good but is permanently unhappy. They are asked for the reason. The one who smiles has learned how to cherish every possible scrap of joy, the other takes the good for granted but fears its loss.”

Pain is a feature of the lives of all the Palestinian refugees here. It comes in many forms. There is the memory of their brutal driving out from their homes and country of Palestine by the Israeli forces in 1948, a memory vivid and personal for a few, like the feisty 90-year-old who regularly calls on Fadia of an afternoon, or passed down through the generations born in exile since then. That pain has been followed by many, many more scenes of shelling, bombing, home demolition, killings and injuries here at the hands of Lebanese factions. I knew of the massacres in Sabra and Chatila committed by Phalangist forces with the connivance of Israeli troops under Ariel Sharon’s command but Fadia reeled off no less than nine years of attacks she has known. She has had her home bombed into rubble six times, four members of her family killed, including her husband and one sister, and has been displaced from camp to camp. It seems to be happening again in 2007 with Nahr al-Bared camp under attack by the Lebanese army since 2 May, and all the half-buried memories of past atrocities resurface.

Fadia well recalls the journey from the south to Nahr al-Bared, which became their home for a while, when she was eight. At that time Lebanese factions were manning roadblocks at which travelers were made to say the Arabic word for tomato, a give-away for Palestinians whose pronunciation differs from the Lebanese. Fadia’s mother is Lebanese and had warned the children to stay silent and let her do the talking so they passed, but it was a death sentence for others. One of Fadia’s aunts witnessed a man identified as Palestinian in this way literally torn apart, his legs tied to two jeeps which drove in opposite directions. Images like that remain seared into the memory.

There are also the day-to-day pains of life in the terribly crowded conditions of the camp amidst poverty and dust from which there seems no escape. Burj al-Barajne has a population of some 20,000 in a space about one kilometer across, the houses rising story above story skywards as they are not allowed to build in any other direction. One day Fadia fears they will no longer see the sky. The tangles of two-core flex with makeshift junctions wrapped in insulating tape that carry electricity from home to home periodically explode with short circuits and fires that kill every year. It is a danger present in the kindergarten too where leaks in the roof cause water to seep into light fittings. Fadia wants to put a new roof over classrooms but is out of funds. Any health and safety inspector would have a breakdown here! There are, of course, no such officials.

At least half of the population must be children. There is no space for them to play nor can they have anything like what we might call a normal childhood. In Fadia’s kindergarten is a small garden, the only one in the camp, and there is an area about the size of a small basketball court under a tin roof to shield it from the worst of the sun’s heat. Here, during our activity time, the boys try to kick a football about. Neither I nor the young female kindergarten teachers know much about the rules of the game and left to themselves the boys usually end up in arguments. Football is a craze but opportunities do not exist.

The little oasis of Fadia’s kindergarten has Disney characters painted on the walls as well as some flowering trees and is Fadia’s attempt to create “something beautiful for the children.” That beauty is sorely needed. The walls of the neighboring buildings are pock-marked with bullet holes from one of the invasions of the past and there still are piles of rubble from houses that once existed near Fadia’s home. The TV news programs which are watched in most homes give endless coverage of well-fed and well-dressed leaders meeting in air conditioned surroundings and talking, mixed with more pictures of dead and dying in attacks in Iraq, Gaza, West Bank, Lebanon, with tanks and soldiers and destruction and weeping relatives. Nothing gets better here and the temperature has reached 40 C. I am assured it will get hotter still.

I learn of another pain as the results of the exam 13-year-olds must sit at the UNRWA schools they attend after kindergarten come out. One of the teachers and her son, Abed, go home in tears. He has failed and that means the end of his schooling. Employment is almost unobtainable even for those well qualified, but holding a Palestinian ID. For 13-year-old drop-outs there is just the street with all the possibilities of bad company, drugs and crime. Fadia says at least 100 boys are in Abed’s position. It is one reason for her wish to give the little children English teaching so they are not at such a disadvantage when they move up to UNRWA schools. Her teachers are so glad of any help at all and come daily unpaid after a tiring school year to meet me and then lead the activity times. I can do so little but my presence is so warmly appreciated. Staff and children tell me they love me and I feel deeply humbled by their warmth, generosity and courage.

Alison Phillips is a 67-year-old retired Scottish school teacher committed to nonviolence who in 2002 and 2003 traveled to Israel/Palestine where she met various representatives of peace groups in Israel and the West Bank and volunteered with ISM for six weeks in Rafah. Denied entry in 2004 by Israel for reasons of “security” she worked with Palestinian refugees in Lebanon including in a kindergarten in Burj al-Barajne Camp from which she recently returned.

Related Links