New Orleans, United States 10 August 2006

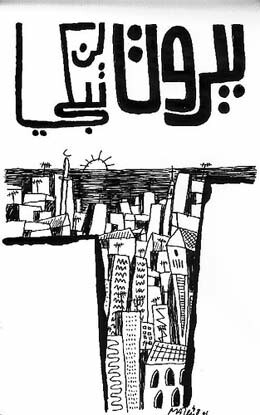

“Beirut won’t cry” by Mazen Kerbaj. View more of his work.

“How?” I asked.

“I’m from Beirut,” she said. In those three words, she summed up an understanding of survival, of resilience, of allegiance to place.

I heard from Rim just a few days ago. She writes that she is without hope, that “when this is over” she will leave that “part of the world” with her husband and child.

More recently I made another friend through my work with Meena, a bilingual Arabic/English literary magazine I co-edit with Egyptian poet Khaled Hegazzi. Rasha was in New Orleans to visit friends. She visited with us, drinking hibiscus tea and chatting. She had just been on the “destruction tour” that locals give to visitors, showing them all the places that were destroyed and, nearly a year on, have not been rebuilt.

“You know, we do the same thing?” she said. “In Beirut, we take people around to look at the destruction.” She said it is a mixture of evoking pity from the visitor, of taking pride in surviving, of needing others to witness it, to see first-hand what has happened. Knowing that there was another place that did the same thing, that this macabre ritual was enacted by another city that had been doing it longer than we had, somehow comforted me. We also talked about the politics of rebuilding the city, of trying to preserve its cultural integrity and how the citizens sometimes become the living memory for their demolished history.

Rasha and I agreed to begin a dialogue about our two cities, of their proud attempts to rise from their respective destructions. I wrote the first installation and sent it to her not even one month ago. She was to reply after she moved back to Beirut from New York on July 11th. Needless to say, our dialogue has changed, and those conversations and comparisons which took place so recently now seem quaint and distant.

Now, each morning, I wait to see if there is a “siege note” from Rasha, dispatches she sends about her experiences in “Ras Beirut” as she watches her country destroyed, as she tries to understand the “consensus that agrees to watch Lebanon burn.” I am filled with dread each morning when I open my email, the dread of not hearing from her and fearing the worst, and the dread of getting her notes and reading what she and her countrymen and women must endure. In the last few days, she reports of her obsession with the bodies left under the rubble.

The most difficult part of hearing what is happening is the fact that I am a citizen of a country that is part of the consensus, that it seems the United States is the only voice that objected to the cease fire called during the original meeting in Rome, and that it supports the war to the extent of supplying the actual missiles. I read a quote by an Israeli official the other day: “Between God and us is the U.S.,” and I once again recoiled from the power my country has usurped from its people and the power it exerts over the world.

I am also disgusted by the way in which western media portray this conflict, by their ignorance of the culture and history of the entire Middle East, of the way they conflate all resistance to power with “terror,” of their complicity in continuing the belief that the quality of Arab blood and brown skin is somehow inferior. I am sickened by the way they spin the chronology of the conflict, the way they ignore the bombings on the beach in Gaza last month, which contributed to this escalation, and of the way they have made the deaths of hundreds of civilians somehow equivalent to the capture of two Israeli soldiers. I search for alternative news sources, for blog postings from Lebanon, and, of course, the news from Rasha.

As I always do when my heart is anguished and when I feel helpless against the power structures that uphold oppression, I also turn to poetry. As William Carlos Williams famously put it, “It is difficult to get the news from poetry, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.” What I find there sustains me because it is essentially human. One reason we began Meena was to try, on some small level, to restore humanity to our respective languages and cultures. When English words such as “freedom” and “democracy” have somehow been twisted to resonate with occupation and torture, when Arabic script somehow conjures associations with “terror” and extremism, we’ve lost track of the sanctity and beauty of language and, indeed, our humanity.

My work with Meena continues to guide me into gaining a deeper understanding of a world that has been hidden from me my entire life. My friendships and my encounters with the rich world of art and history of Arabic culture are making me more fully human. While this makes the tragedy unfolding that much more clear and painful, it also makes me more determined to seek truth and to attempt to utter it through my work. As I continue to hear news with my mouth agape, I also try to sort through it for the human truth beneath the rhetoric and, indeed, beneath the rubble. I try to write and speak about Rim, about Rasha, to put a face on the suffering so that, perhaps, my fellow citizens can begin to realize their humanity and, thus, the tragedy unfolding in our name. When all else fails, I try to send my spirit and solidarity to them through my poems and through my prayers, and hope for a time when we can begin a new dialogue about our cities, about dignity, about rising again from the dust.

Related Links

Andy Young is the co-editor of Meena Magazine, a bilingual Arabic-English literary journal. A creative writing instructor at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, her poems, essays and translations have appeared in literary publications throughout the US, as well as in Mexico, Ireland and Egypt. She was recently designated a Universal Ambassador for Peace.