Al Jazeera 15 May 2005

From the cemetry of Rashidieh refugee camp, refugees can see the mountains of Palestine. (Arjan El Fassed)

Hidden away in a squalid Palestinian refugee camp is a historical treasure trove that keeps the dreams of many alive. In a corner of the Palestinian refugee camp of Mashook in southern Lebanon, 68-year-old Muhammad Dakwar shows the way into a dusky two-room gallery that he guards with his life.

Inside, ragged pieces of traditional Palestinian garments hang on thin metal racks; decades-old clay pottery and copper plates are neatly arranged on shelves amid a melange of traditional Palestinian household items.

Rustically preserved samples of Palestinian earth - soil, rocks, and olive tree branches - are displayed on poster boards, crudely taped and labelled according to city or village of origin. All are part of what Dakwar says is the only Palestinian museum in exile, and by some estimates, the only Palestinian heritage museum in the world.

Personal sacrifice

Dakwar, a retired UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) school teacher, founded the museum 15 years ago and has run it at his own expense ever since, refusing to charge any entry fee to visitors. It is a cause that has driven him near to the point of financial ruin.

Most of the items in the museum have been generous gifts from Palestinians and philanthropists the world over, but many are purchased out of Dakwar’s own pocket.

“I’ve spent my entire retirement bonus to keep the museum running. I am almost broke, but I am prepared to beg in order to keep this museum open to the public,” he says, admitting he has had to shut down the museum’s website due to the lack of funds.

The museum was established in 1989, but not officially recognised by the Lebanese government until eight years later Dakwar was not given a legal permit to construct the museum until 1997.

Instead, it was listed as the Palestine Committee for Culture and Heritage - a committee, because Palestinians are not allowed to legally establish institutions in Lebanon, according to Dakwar.

Treasure trove

Although small, the museum houses an impressive collection of about 2500 artefacts, including the lock to the infamous Akka (Acre) prison, where the then ruling British detained and executed, some of the first Palestinian fidayin (those who sacrifice themselves) during the 1936 revolt.

It is also a treasure trove of Palestinian currency used during the British mandate, and coins from as far back as the Roman period. The gallery also includes a library with more than 10,000 books and journals, many of them rare editions.

The museum also has on display household items used in Palestine, but imported from Europe or the Americas, such as a Swedish coffee-bean grinder, an empty jar of Old Spice bath salts, and a uniquely designed glass baby’s bottle of English origin.

The mishmash of items persevered in time is eerie testimony to the sudden and urgent departures of the thousands of Palestinian refugees, and all they left behind in the mass exodus of 1948, in unfulfilled hopes of returning within a few days.

Dakwar insists on using the year 1948 - the date of the Palestinian Nakba, or catastrophe, as a benchmark for dating items on display.

“This is no coincidence, to centre the museum around 1948,” he explains eruditely. “I want to make sure people forever remember this date and what it means for Palestinians. This is part of the museum’s purpose.”

Palestine partitioned

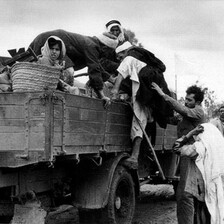

In 1948, Jews declared their state in Palestine after the United Nations voted to partition Palestine, and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were made homeless and forced to flee in the process, their villages subsequently destroyed or depopulated.

Dakwar was one such refugee, hailing from the Palestinian village of Qadeetha near the city of Safad. He sought refuge in Lebanon with his family at the tender age of 11. His village was depopulated by Israel in the aftermath of the 1948 war.

The museum, and Dakwar’s refugee camp, are only 15km away from the border of his Palestine. On clear mornings from high rooftops in the camp, one can see the Palestinian town of al-Naqura, not far from his own village. But the distance may as well be 50,000km away. As a refugee, Dakwar is denied the right to return to his home.

And so he has made it his mission in life to preserve Palestine in his refuge away from home, something he regards as his personal contribution to the Palestinian struggle. He hopes one day to gift the museum to Palestine - when there is a Palestinian government he trusts enough to take care of it, he says.

For now, it will remain an exhibit in exile for Lebanon’s some 400,000 Palestinian refugees, “so they will never forget where they came from, and to where they hope to one day return”.

Laila El-Haddad is a journalist based in the occupied Gaza Strip. This article was originally published by aljazeera.net and reprinted on EI with permission.

Related Links