The Electronic Intifada 23 June 2003

(UNRWA)

Suppose I live in a slave-owning society. As a member of that society, I would have the right to own slaves. If I did own slaves, I would also have a host of subsidiary ownership rights, such as the right to sell them and the right to set them free. But this right has no moral justification. Indeed, it is a pernicious right, one based on the immoral permission to use other human beings as one chooses. Thus, while it is in that society a legal right, it is not a moral right.

Consider now the example of the right to national self-determination, a right that both Palestinians and Israelis claim. This is a political right, certainly. Yet whether it is also a moral right is a controversial issue. Because this right depends on a specifically political concept, namely, that of a nation, whether it has moral justification depends on whether the notion of a nation is a morally good one or not. And the philosophical jury is still out on this question. The point is that legal and political rights, for them to retain their importance and legitimacy, must be ultimately morally justified. This does not mean that all legal and political rights are also moral rights, though some are. But it does mean moral issues are supreme. That is why moral rights are more important than political and legal ones.

Moral rights are supposed to be ultimately neither political nor legal rights. They might be enshrined in legal and political documents and so come to be called “legal rights” or “political rights,” but they would ultimately admit of moral justification. Thus, moral rights are rights that exist prior to or independently of legal, institutional, and political arrangements. In other words, when someone has a moral right, he has a claim that is recognized and justified by moral principles, not legal or political ones. Though, for example, my right not to be enslaved may be recognized by the legal and political institutions of my country, it is ultimately justified by more basic facts, such as human beings’ autonomy and ability to self-determine their lives.

But notice also that to say that moral rights are basic is not the same thing as saying that they are absolute. To say that a right is absolute is to say that nothing and no one can morally prevent the holder of the right from exercising it. Whether any or all moral rights are absolute is another controversial issue, but the consensus among most philosophers seems to be that very few, if any, rights are absolute. That is because in the case of any right one can think of, one can imagine situations in which overriding that right is more morally important than preserving it. Thus, my right not to be killed is overridden when someone kills me in self-defense as I attack him.

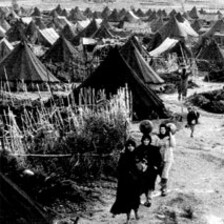

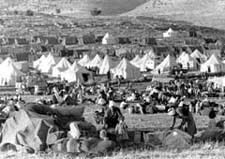

The right of return of Palestinian refugees is a legal and a political right. But it is also a moral one. Notice that when Palestinian refugees claim their right to return, they do not mean by this that they have a right to return to a specifically Palestinian state. Rather, they mean by it that they have a right to return to their homes and villages. Nor do they mean by it the right to return as a national people. Rather, they mean by it a right to return as individuals. Absent from these descriptions, and rightly so, is any specific reference to particular political arrangements.

Palestinian refugees are fully aware that were they to return, they might have to become Israeli citizens. My point is that the language of the right of return indicates, because it is devoid of any mention of specific political arrangements, that the right in question is a moral, and not just a political, one. This is not to say that political claims and arrangements do not factor in. They do. But they are not, as such, part of the idea of the right of return. They are, logically, secondary ones, to be discussed and managed once the right of return is recognized and steps for its implementation are taken.

But how can the right of return be justified as a moral one? Two compatible justifications can be offered. The first is simple: a refugee is someone who is either directly or indirectly forced to leave his or her home. Morally speaking, and everything else being equal, when I am forced to alter the course of my life by an external power, then I have the moral right to be given the option, if feasible, to return to that course of life. Because being uprooted from one’s home and village is a stark example of being forced to alter one’s life, then one has the moral right to be given the option to return to one’s earlier life, and this implies the option to return to one’s home and village. Since there is no conceptual requirement that one has to live under a particular political arrangement or constitution for justifying this option, the right of return is a moral right.

The other way of morally justifying the right of return is that without rights to secure our basic physical and psychological needs, our ability to lead well lived and autonomous lives could be severely hampered by leaving it hostage to the contingencies of life, including human and non-human contingencies. Because a sense of an intact identity is necessary for psychological well being, and because being a refugee violates this sense of identity by forcing an alien way of life on the refugee, a refugee’s ability to lead a well lived and autonomous life is seriously hampered.

The reason why refugees’ sense of identity is endangered is because the connection between their life, on the one hand, and their home, land, and history, on the other, is severed. Thus, the right of return is a moral right: it allows for the restoration of a refugee’s sense of identity, a sense needed for one to lead a good life. I consider the first type of justification as more plausible and so more powerful. Nonetheless, I mention the second type so as to alert the reader to its existence. Since the historical record clearly shows that the Palestinians who left Palestine in 1948, 1949, and 1967 were indeed either directly or indirectly forcibly removed by the nascent Israeli army, then they are refugees and so have a moral right of return.

It is important to emphasize the fact that the right of return is a moral, and not just a political, right because moral rights are bedrock. They are more fundamental than political and legal rights. In other words, they often trump such rights. For example, I may have a legal right to own slaves, but because I do not have a moral right to do this, then the legal right ought to be done away with. Consider another example. The national right to self-determination, a political right, cannot always have the upper hand.

If a nation exercises its right to self-determination and in doing so displaces a whole other people, then these latter people would have a right to return. The reason is that exercising a political right cannot come at the expense of others’ moral rights, unless not exercising the political right would endanger even more serious moral rights. So unless there are good reasons to override someone’s moral rights, these rights cannot morally be tampered with or compromised.

Granted that the right of return of the Palestinian refugees is a moral right, should it be implemented? Given that it is one thing to recognize a right and another to implement it, are there any good reasons why this particular right should be overridden? There have been a number of positive answers given to this last question. I believe that none of them succeeds. But this is a territory that requires separate treatment. The least that can be said for now is that given that the right of return is a moral right, whatever reasons one gives for not implementing it would have to be weighty indeed.

Raja Halwani is associate professor of philosophy at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He has published numerous articles in the area of moral philosophy.

Related Links