The Electronic Intifada Edinburgh 31 August 2012

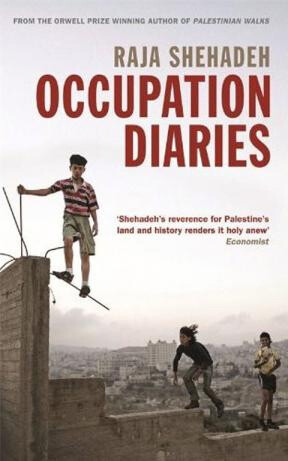

Fans of Raja Shehadeh’s previous work — books such as Strangers in the House, A Rift in Time and, perhaps most famously, Palestinian Walks — will not be disappointed by his latest offering, Occupation Diaries. In characteristic Shehadeh style, it blends loving description of the West Bank’s scenery, nature, culture and architecture with a sharp but calmly-narrated loathing of the oppression, injustice and sheer physical ugliness of the Israeli occupation of Palestine.

Occupation Diaries spans a two-year period, from December 2009 to December 2011. As such, it touches on major events that will be familiar to most readers of The Electronic Intifada, such as the uprising in Yemen, the Nakba Day march of thousands of Palestinian and Syrian youth to the border of the occupied Syrian Golan Heights, and the killing by Israeli commandos of nine solidarity activists on board the Mavi Marmara, as well as lesser-known stories and the everyday concerns of a Palestinian living in Ramallah.

Typical of Shehadeh’s style, though, is his use of personal anecdote to discuss significant but less headline-grabbing issues. A journey from Ramallah to Bethlehem provides an opportunity to talk about Jewish extremism and terrorism as his driver recounts how, 11 years earlier, his brother was murdered by an American-Israeli settler, Jack Teitel, who had smuggled a gun in his luggage from the US and set off into East Jerusalem looking for a Palestinian to kill.

Only when Teitel’s extremism led him to target a Jewish Israeli academic was the threat he posed taken seriously, although the police had suspected him for more than a decade (11-16). And the May 2010 refusal by Israel of an entry visa to Noam Chomsky leads Shehadeh to comment that: “the veneer of civilization and decency in Israel is getting thinner. But I was wrong, it has vanished entirely” (32).

Also typical of Shehadeh is his willingness to criticize the Palestinian Authority and aspects of Palestinian society for what he sees as their flaws. Of the PA’s cancellation of municipal elections, he comments that: “Fatah could not get its act together and would have lost … Fatah didn’t want the truth about their unpopularity to be revealed” (44).

After Fatah activists break up a meeting of activists demanding that negotiations with Israel are not resumed until settlement-building ends, he despairs: “I felt the fear of a police state approaching” (86).

Critical of Palestinians, critical of Israelis

It’s not only the PA that comes under Shehadeh’s sharp gaze, but the wider fragmentation and deterioration he perceives in Palestinian society.

He condemns the aid-fueled economic “boom” in the West Bank as “A scheme devised by European and US funders, a policy of anti-insurgency not dissimilar to that pursued in Northern Ireland … It seems to have worked in Northern Ireland, thinks [former UK Prime Minister Tony] Blair, so why should it not in Palestine?” (43). Meanwhile, Shehadeh is bemused and disappointed by the experience of being offered strange, fake “international” food in a Ramallah restaurant by waiters who refuse to respond to him in Arabic (44).

In the opening passage, he and his companions on a hike in Wadi Qelt encounter another group of walkers, conservatively-dressed Muslims including a woman wearing a niqab (traditional face covering). Of an altercation in which neither side emerges particularly honorably, Shehadeh observes: “I thought of the different worlds Palestinians now inhabit. One group is devoutly Islamic, while another is demonstratively secular, liberal … It felt as though the small bit of Palestine left to us was being pulled apart” (6). Meanwhile he is scathing about fellow Ramallah residents for whom “land now only means investment and money” (92).

Raja Shehadeh has emerged as a favored voice of Palestine to liberals, in the UK at least. It’s easy to see why. He defends the two-state solution as “the only realistic one” (33), although his desired option is the multi-ethnic, multi-faith communities of the Ottoman era (as depicted in A Rift in Time) and he eschews the starry-eyed take on this period of some neo-Ottomanites.

A rare Palestinian voice

Shehadeh is himself middle-class, secular and highly cultured, quoting Western writers and intellectuals as well as Arab ones. His writing is laced with a powerful nostalgia for a diverse, tolerant, secular Palestinian society where “it was so normal … for Christians, Jews and Muslims of this land to participate in each other’s religious feasts” (31), where his grandmother could take afternoon tea in an elegant hotel where international artistes performed and, even in “conservative Ramallah,” men and women danced together in the evenings (51).

At times he is also optimistic — perhaps excessively — about human nature, especially that of his Israeli occupiers, as when he notes that “No wonder Israelis are not allowed to visit this side of the wall. How ashamed they would be if they saw what was being done to their neighbors in their name” (22).

This is by no means a criticism. Raja Shehadeh never claimed or claims to be presenting the gritty portrayal of working class or refugee camp Palestinian hardship. He is honest in acknowledging the personal nature of his writing — these are, after all, his diaries. He is brutal in critiquing some darlings of liberal commentators on Palestine, such as the Academy Award-nominated film Ajami, whose stereotyped, decontextualized portrayals of violent, emotional Arabs he calls the “final insult” to Jaffa, the city his parents fled (72).

The particularities of Shehadeh’s status — unlike most West Bank Palestinians, he has an ID which allows him into Israel — and his cultured, middle-class existence might not be representative of the reality of occupation for many of his fellow Palestinians. Indeed, he is one of the rare Palestinian voices who are still able, from first-hand experience, to contrast life in the West Bank with that of Palestinians living within Israel.

But despite his usual elegant, quietly impassioned prose, this is an angry book which defies standard Western liberal support for the PA and Israeli agendas. Through the moments of despair at the duplicity of the Israeli regime and the apathy of the international community, “we have no intention of going anywhere,” he concludes (204).

Sarah Irving is a freelance writer. She worked with the International Solidarity Movement in the occupied West Bank in 2001-02 and with Olive Co-op, promoting fair trade Palestinian products and solidarity visits, in 2004-06. She is the author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-author, with Sharyn Lock, of Gaza: Beneath the Bombs.