The Electronic Intifada 7 June 2016

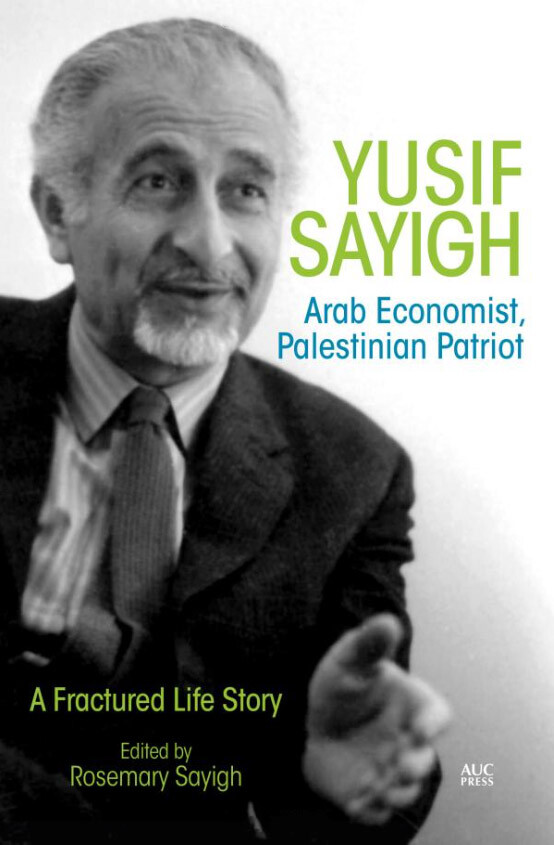

Yusif Sayigh: Arab Economist, Palestinian Patriot: A Fractured Life Story, edited by Rosemary Sayigh, American University in Cairo Press (2015)

A number of important Palestinian memoirs have been published in recent years — among them, those of the musician Wasif Jawhariyyeh, the early Arab feminist Anbara Salam Khalidi, and the politician Shafiq al-Hout.

Yusif Sayigh’s life story, narrated and edited by his wife Rosemary (herself an eminent anthropologist and activist), is a significant addition to this list.

Its importance stems from two things.

Firstly, it is a wonderfully frank account of Yusif’s long and eventful life, from 1916 to 2004. One wonders if the fact that it was recorded by his wife, rather than written as a formal biography, inspired such openness on subjects ranging from sex (and the accompanying guilt) to Yusif’s tempestuous relationship with Yasser Arafat.

Yusif describes his stint at the Palestine National Fund as “hell” due to Arafat’s constant interference and refusal to follow rules and norms.

This robust language is also applied to the everyday. For example, Yusif comments of one of his mother’s suitors that he “would commit suicide rather than be his son!”

Most of the book consists of transcribed speech, edited with a light hand. The result is lively and highly readable, although occasionally it’s possible to see Yusif’s shifting train of thought. This can sometimes be a little confusing, but it’s worth maintaining the intimate, buoyant feel.

Secondly, the range of experiences encompassed by Yusif’s life story is remarkable.

Ordinary people

As Rosemary discusses in her introduction, part of her work was to convince Yusif that his life was worth recording — that “ordinary” people’s memories are as important as those of national leaders.

The stories of Yusif’s early life set the tone for much of the book, combining everyday, personal details — animals, neighbors, clothes — with larger events.

In one early story, Yusif’s family was forced in 1925 to flee their home in Kharaba, near Deraa in southern Syria, because as Christians — Yusif’s father was a Protestant pastor — they were seen as associated with the French colonial forces against whom the Druze were fighting.

Returning to his mother’s village of al-Bassa, near Akka, signaled a shift from his isolated Syrian home to a diverse, colorful coastal culture where different denominations of Christians and Muslims mixed and traditional aspects like “folk” medicines coexisted with newer notions like cars and rapidly changing gender relations.

Although the Sayigh family was not well off, Yusif’s father had contacts throughout Palestine and Lebanon through his pastorship. These meant that Yusif and his siblings — including the poet Tawfiq Sayigh and historians Anis and Fayez — gained an elite education, but often through scholarships.

Yusif recollects that in his school days, there was already widespread awareness of Palestinian politics and British imperialism amongst the boys.

The chapters on Sayigh’s time at the American University of Beirut are studded with major political and intellectual names, including the future historian Albert Hourani, the Arab Nationalist thinker Constantin Zurayk and philosopher and diplomat Charles Malek, who helped to draft the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Yusif himself became involved in the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), a political movement which promoted Syrian, rather than pan-Arab, nationalism. Its leader, Antoun Saadeh, was executed by the Lebanese government in 1949.

Yusif, however, moved away from the party, disturbed by the cult of personality surrounding Saadeh, and his politics took a more pan-Arab direction.

These tales of political student life are intertwined with a whirlwind of socializing and sports, in which the contradictions of mid-century Beirut are highlighted by juxtaposing glamorous Hollywood films starring the likes of Orson Welles and Greta Garbo with Yusif’s brother Fayez spending a year disguised as a monk to escape arrest for his SSNP activities.

After graduating in business administration, Yusif took on a range of managerial jobs, including overseeing the Tiberias Hotel in the Galilee region of Palestine during the Second World War. Wartime guests included the famous Syrian Druze singer Asmahan, who used the hotel as a base for her work collecting intelligence for the British.

It was via his administrative and managerial talents that Yusif became involved with the Palestinian national movement in earnest. As Director General of the Arab National Treasury in 1947, he planned the tax system for the expected independent state of Palestine.

Bread and dignity

But despite his admiration for such figures as the Mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini, Yusif was critical of the movement’s focus on personalities and lack of organization. His stories of refusal by the Arab regimes, notably of King Abdullah of Jordan, to help the Palestinian forces defending Jerusalem are bitter and regretful in tone.

In a remarkable section of the book, Yusif describes his long period as an Israeli prisoner of war, taken captive after the surrender of his small patch of West Jerusalem, and held in several different camps and witnessing the extrajudicial executions of fellow prisoners.

It is here that the brisk efficiency of Yusif’s character really reveals itself, notably in his exasperation with fellow POWs who responded to defeat by “quoting the Quran” instead of learning from the failure and developing new military strategies.

This unemotional, practical sensibility along with his intense frustration with Arafat — among others who insisted on a personalistic and often corrupt style — appears to have been the driving force behind Yusif’s attempts to build stable, democratic economic institutions within the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Yusif never portrays himself as a hero in these stories — he is often self-deprecating and willing to give others credit.

But reading between the lines, we find a humane and thoughtful man who devoted much of his life to building a practical vision of how a just and free Middle East might look.

In the final chapter describing Yusif’s belief in incorporating social justice and the impacts of colonialism into economic analysis and planning, Rosemary notes that his first book was called Al-khubz wal-karama — Bread and Dignity. As she observes, it was a motto that embodied much of his life’s work.

Sarah Irving is author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-editor of A Bird is not a Stone.

Comments

I have only a short comment

Permalink rafik replied on

I have only a short comment or let say a point of view which is my observation on the Palestinian auto/biography. when we read them we find them as a history and memory for the palestinian nation in general, i read Mourid Albarghuthi's autobiography "i saw Ramallah" and Jebra Ibrahim Jebra "The First well: Bethlehem Boyhood" and Abdel Bari Atwan" A country of Words" . All of them tell the reader about the historicl suffering of the Palestinian people during the per-Nakba or Poet-Nakba.

ordinary people

Permalink Jamiel Sabbagh replied on

Great review. I agree, the stories of 'ordinary' Palestinian people through the 20th century enriches and provides immense value to our contested history. My Grandmother grew up in Al-Bassa around the same time as Yusif Sayigh. She witnessed the British massacre during the 1936-39 civil war. Events like these need to be recorded and remembered.

Jamiel Sabbagh