Refugees International 14 July 2003

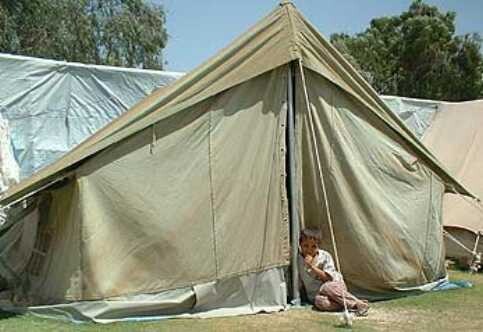

On the grounds of the Haifa Sports Club in central Baghdad, 250 Palestinian families live in a tent camp, sweltering in heat that exceeds 125 degrees.

The camp’s residents are mostly women, children and elderly people. To drink, they must haul water from distant faucets. Mothers complain that their children can’t sleep because of the heat, and the frightening rattle of gunfire during the night.

What’s shocking is not that there are unhappy refugees in Baghdad in the wake of the war but that for more than two months the U.S.-led Coalition Provisional Authority did not know they were there. Yet these families are just a small sliver of the 130,000 displaced people living in Iraq, families whose existence is not recognized, whose needs are not being met - not because the coalition doesn’t care but because it lacks the systematic strategy and clear vision necessary for success. If there is a master plan for reconstruction, the public has not seen it, and without it, micro-level problems become chronic as the Iraqis grow impatient and restless.

From top to bottom, no one seems quite sure where to go to find solutions. Being an Iraqi with a problem is like standing in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles holding a number no one calls. Though accompanied by a military escort, one Iraqi woman embroiled in a property dispute spent two weeks simply trying to find the Civil Affairs Office to which she had been directed. No soldier or coalition administrator even knew where the building was.

The United States appears firmly committed to one policy: holding the United Nations at bay. Unfortunately, minimizing U.N. involvement deprives the U.S. of the U.N.’s long experience in Iraq and its emergency-response skills. In past conflicts - in Kosovo, for instance, and more recently Afghanistan - the U.N. has been involved in all facets of reconstruction, from food distribution and water and sanitation projects to the training and equipping of police forces.

In Iraq, all of these services have been placed under control of the U.S. Department of Defense, which has demonstrated little capacity to fill the coordination void. The U.S. is also making little effort to use humanitarian relief organizations now operating on an ad hoc basis in Iraq.

Another problem is that due to a lack of security, coalition officials are required to travel with heavy military protection, submitting proposed itineraries 48 hours or more in advance. Where the situation is most hazardous - and where the need often is most dire - travel is simply forbidden. The inability of officials to move freely, even in Baghdad, explains how refugees could go unnoticed and why problems such as a rising number of homeless street kids and the maintaining of order go unresolved.

For more than two months, the coalition did not acknowledge responsibility for the Palestinian families at the sports club. The Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees and other organizations provided some emergency relief and stood ready to resettle them but received no U.S. guidance or authorization. Housing in the city is under coalition control, and without coalition approval, neither the camp nor its residents may be relocated.

In mid-June, after a scramble through three different ministries, representatives of the coalition and the U.N. refugee agency finally got together to discuss the subject. A coalition official visited the site and the U.N. offered to start repairs on a building that could be a secure and permanent shelter for the refugees. But the coalition authority has yet to approve the plan. No further action has been taken.

Ethnic clashes dispossess new families each day, and the number of economically displaced Iraqis grows. Solving these problems would breed confidence in the potential for a new and stable Iraq. But without a comprehensive plan and a strategy to implement it, the coalition’s vision of a new Iraq will remain, like the families camped at the Haifa Sports Club, overlooked and in limbo.