The Electronic Intifada 24 April 2025

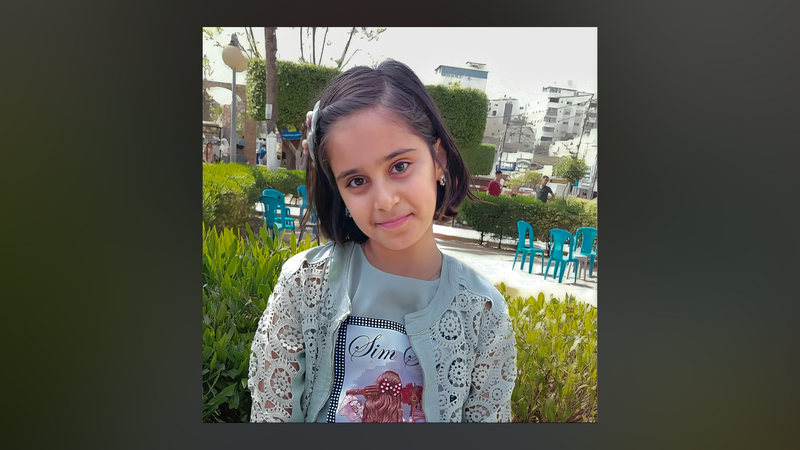

Rahaf Alnaami

I watched my sister Rahaf, eight years younger than me, grow up ever since the day she was born in 2012. She was my one and only beautiful, beloved sister.

She in turn watched me and I always tried to be a good example for her to look up to, a supportive sister and friend at all times.

Rahaf had a stubborn streak and we would sometimes argue because of that.

Last October, we got into a tiff when Rahaf wanted to take a training course to learn to produce short films.

I objected, fearing for her safety while she was out recording amid the bombardment. I felt that the timing wasn’t right.

“She’s not a little girl anymore, let her go, learn something new and become independent,” our mother told me.

I relented when I saw how determined Rahaf was and when she promised to be careful and not stay out too long.

We would always find our way back to each other at the end of the day, as if nothing ever happened.

Rahaf was always by my side during this genocidal war.

At one point, a place nearby us was bombed. Completely exhausted, I broke down. When Rahaf saw me, she sat beside me and joined me in crying.

The next day, I asked her why she cried. Was it because she was scared of the sound of the bombing?

“No,” she said. “I cried when I saw you crying. I didn’t want you to cry alone.”

As her older sister, I felt a deep responsibility for her and wanted to protect her, even though I never showed it. I wanted to teach her to be strong and independent.

But I couldn’t protect Rahaf or save her from the Israeli airstrikes.

Supportive

Rahaf was my first and biggest fan. She was so supportive of my writing.

She had asked me to write about Hamed Ashour, who was teaching her to make short films.

Hamed, who is also a poet, told me his story of displacement from Rafah in southern Gaza.

Rahaf was so enthusiastic, knowing I would be deeply moved by and inspired to write Hamed’s story.

I finished writing the piece on 28 December 2024.

I was eager to tell Rahaf. But it was 1 am, too late to wake her up. So I left my notebook open on a table so that I would remember to tell Rahaf about it in the morning and went to sleep.

I felt like only minutes had passed before I was jolted awake by debris falling on me. I heard my cousins in the house next door scream just once.

Then silence followed.

I had always wondered – do people really not feel anything when a bomb hits them?

In those moments of silence, I realized that this was true.

Other questions soon followed: Why was I still alive? Why wasn’t I hearing the voices of my sister or my parents?

I couldn’t breathe or move at first. My whole body ached.

But I kept trying until I was able to push a piece of rubble away from my face with my hand.

I heard my brother, Hamoda, crying on his bed beside me. I told him to try to free himself from the debris, but he told me that he couldn’t.

Then I saw a dim light flickering in the distance and moving toward me.

Someone using a phone as a flashlight shouted: “Which house was bombed?”

I recognized his voice – it was my cousin Mohammad, who lives in the house behind ours.

“Mohammad, I’m here. Come get me out – my brother is next to me,” I cried.

Mohammad told me to hang on as he went to bring his dad – my uncle – to help.

While I waited, I kept telling myself, “It’s just a nightmare.”

Was Rahaf gone?

About five minutes passed – though it felt like hours – before the voices of my neighbors grew louder as they dug through the rubble to find us.

I heard my father screaming for help.

My cousins pulled my brother out first and carried him to the ambulance before they came back for me.

Despite all the people digging to pull me out, the first person I saw was my father.

I felt safe for a moment. He thanked God when he saw that I was alive.

I was taken to my uncle’s house next door to ours. Everyone was crying.

My aunts and grandmother started sobbing even more when they saw me.

From what my aunts and cousins were saying and the questions they were asking me, I pieced together that my uncle’s house – adjacent to the room in which Rahaf was sleeping – had been bombed, killing several of my cousins.

I could feel there was something else they weren’t telling me.

Was Rahaf gone? I resisted the idea.

“Where are my mother and Rahaf?” I asked. “I didn’t see them. I didn’t hear their voices.”

No one answered.

Even though I could barely stand, I stepped outside and looked at the ruins of my home, where neighbors were still searching for the missing. I wondered, how did I get out of that rubble?

Someone told me that my mother was fine and that I should go inside so that I wouldn’t see more.

The author’s destroyed home.

The suffocating reality that Rahaf was gone started to sink in.

That night before the bombing, I had sensed that something was wrong, that something might happen to Rahaf.

Rahaf was unusually calm that evening. She really wanted a kiwi, so she went and bought one for herself and shared some of it with me. She also brought home an apple that she left for me to eat the next day.

When I said that I wanted her to buy me a kiwi just like the one we shared the next day, she immediately agreed. This surprised me – she would typically push back, even if deep down she was fine with it.

I kept resisting the idea that something terrible happened until my mother entered the room where I had been taken to at my uncle’s home. She was sobbing and alone.

“Where are my children?” she cried.

As soon as my mother glanced at me, she hugged me and held on as if trying to keep me from slipping away too, while repeating: “Rahaf left us! She left us! She left us, Shahd!”

My father collapsed when he heard my mother and cried out: “Rahaf was my soul. They took my soul!”

My cousins rushed me, my mother and my father to an ambulance. I lay my head on my mom’s leg and cried.

All I could think was: Is this real or just a nightmare?

Last farewell

We arrived at the emergency room at Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital at around 5 am. My brother Hamoda and my neighbors Amona, 20, and Halima, 26, were all injured.

My right leg was injured and I was in shock.

When my uncle came, I begged him and my mother to take me to bid farewell to Rahaf.

When we arrived at the morgue, my uncle helped me sit beside Rahaf.

I looked at her closely.

She seemed as if she were only sleeping, with a little blood on her face.

I touched her. She wasn’t cold.

“Goodbye, my little, beautiful sister. Say hello to Eman for me – we miss her,” I whispered to Rahaf.

My friend Eman was martyred at the beginning of the war while she was praying. Rahaf loved her so much. Now that they are together, I’m sure Eman is taking care of Rahaf.

Meaning of sisterhood

That first night in the hospital was a blur of pain and confusion.

I was moved to a room with three little girls, one of whom looked so much like Rahaf that, for a moment, I thought it was her.

Her fair complexion, her soft, silky bob, her lively spirit and constant movement – everything about the girl reminded me of Rahaf. I couldn’t stop staring, aching to hold what I had lost forever.

The hours stretched on and sleep never came.

I lay awake, consumed by the emptiness, the overwhelming grief and the unbearable longing for the sister I would never, ever see again.

Rahaf was the one who made me genuinely understand the meaning of being a sister.

She never missed an event or celebration that I was involved in – whether a festival, a school play, or modest community event.

When I was nervous about reciting a poem before an audience during an annual event at the Islamic University of Gaza, I saw Rahaf beaming with pride as I stepped on the stage. She was smiling wide and pointing at me while telling everyone around her: “That’s my sister!”

Her being there – proud, present and loud in her love – made everything feel safe.

She shared my tears, my laughter, my joy and my sorrow – she shared everything with me.

But now, I can no longer share my life with her – not the small victories, such as finishing my story about Hamed after my notebook was pulled from the rubble soaked and smeared.

Not the quiet moments, like giving her my feedback on one of her drawings.

Not even the joy of telling her Hamed’s story would finally be published.

Rahaf, I miss you so much.

All images courtesy of the author.

Shahd Alnaami is a student and writer from the Gaza Strip.