The Electronic Intifada 15 April 2013

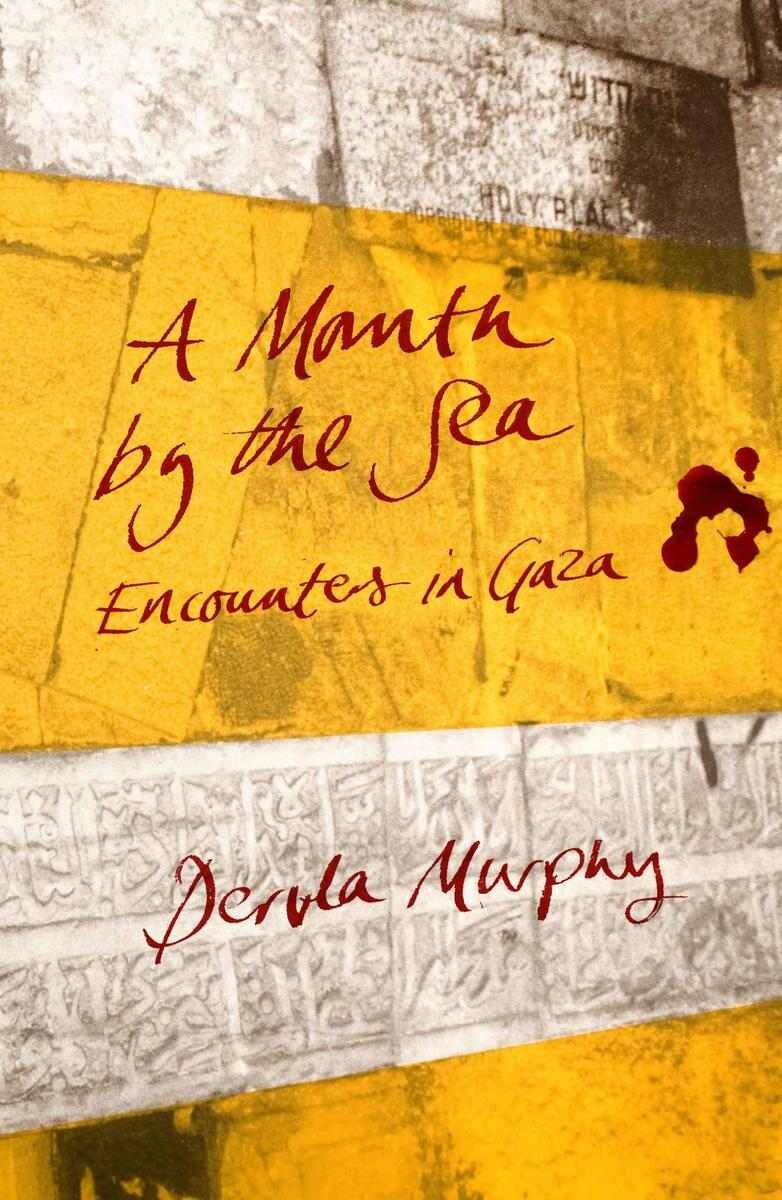

Dervla Murphy’s latest book A Month By the Sea: Encounters in Gaza has an ironic and provocative title. At first, it conjures up images of a sun-dazzled vacation. Then you realize that the sea in question is heavily polluted with human excrement because Israel has bombed Gaza’s sewage treatment facilities; that fishermen who depend on this sea are regularly attacked by the Israeli navy.

Now in her eighties, Murphy is described as “Ireland’s pre-eminent travel writer” by her publishers, Eland. But calling her a “travel writer” appears too reductive. Murphy shuns the “what to eat, where to stay” formula typical of Lonely Planet or Time Out guides, focusing more on political analysis than on Gaza’s admittedly scarce tourist attractions.

Her stay in Gaza — during the summer of 2011 — came after she spent five months in the West Bank (renting a room in the Balata refugee camp near Nablus), as well as three months inside present-day Israel. She is planning a separate book about those experiences but there is no doubt that everything she witnessed in Palestine reinforced her long-held disdain for the Zionist project. Israel, she writes, is an “artificial creation, founded on self-deceit and bolstered by the success of world-deceiving propaganda.”

Operation Cast Lead — Israel’s all-out offensive against Gaza in late 2008 and early 2009 — offered a master-class in that type of propaganda. In a grotesque distortion of reality, Israel presented its bombardment of an already besieged population as an act of self-defense.

“Strident” criminality

Murphy seems repelled by the frequently superficial and testosterone-fuelled nature of war reporting. When a local chaperone takes her to meet surviving members of the Samouni family — who lost 21 members in a January 2009 massacre — she is “vaguely uncomfortable” about how visiting the scene of the crime has become a “must” for foreigners in Gaza. Her unease disappears, however, when she senses that the Samounis appreciate gestures of solidarity.

Whereas other authors might limit themselves to recording the family’s recollections, Murphy puts them in a broader context. The weapon used in the massacre, she notes, was American, recalling that while Barack Obama “made his famous Islam-friendly speech” in Cairo during June 2009, “the US was replacing the many multi-ton bombs dropped on Gaza” earlier that year.

Her contempt for the profiteers of occupation is equally apparent when she meets Nasser Abu Shabaan, a surgeon in Gaza City’s al-Shifa hospital, who has chronicled the effects of “innovative” weapons such as white phosphorous. Post-mortem images saved on his computer show “melted brains, shredded lungs, cooked livers, exploded kidneys,” Murphy writes, asking if “arms manufacturers and their politician customers ever look at such pictures.”

Murphy argues that “Zionist criminality is becoming ever more strident and arrogant” to the point that it is no longer shocking to compare Israel with Nazi Germany. She draws this conclusion after hearing an unnamed Palestinian friend posit the theory that Israel may have subjected Gaza’s 1.6 million inhabitants to collective punishment because of a “hideous hangover from the Holocaust” (Murphy’s words). When she confesses not to understand the logic behind this reasoning, her friend replies: “We’re not talking about logic. We’re talking about something very deep and dark and twisted. Something so sick that the international community is afraid to go near it.”

No love for Hamas

The “international community” referred to is comprised of the US and its lackeys, of course. Speaking of America’s lackeys, Murphy denounces senior European Union diplomats who occasionally pop into Gaza for a few hours but refuse to meet Hamas representatives.

Murphy has no time for the “we don’t talk to terrorists” line parroted by those diplomats. She displays a firm grasp of Hamas’ history, lamenting that the “outside world” paid scant attention to the strategic thinking behind a 2004 document on Israel’s “anticipated withdrawal from the Gaza Strip,” in which Hamas sought to gain international recognition as what she calls a “legitimate resistance movement.” A lengthy conversation with a founding member of Hamas, Mahmoud al-Zahar, leads her to praise him as a man of “integrity.”

Despite being slightly in awe of the “handsome” al-Zahar, she does not romanticize Hamas. On the contrary, she decries the restrictions on personal freedom that it has imposed in Gaza. She decries, too, patriarchy in Palestinian society and is especially appalled by “honor killings” — the murder of women or girls who disobey rules (stipulated by men) on relations between the sexes. The practice reminds her of how the Catholic church in her native Ireland ran the Magdalene Laundries until the late twentieth century, effectively imprisoning women who got pregnant out of wedlock.

Harsh words for Ireland

Murphy, incidentally, reserves some of her harshest words for the Irish government’s willingness to engage with Israel. She excoriates Eamon Gilmore, the country’s foreign minister, for attending a film festival sponsored by the Israeli government in 2011. By doing so, Gilmore gave a boost to the “Brand Israel” initiative, which uses art and sport in an attempt to promote Israel as a “normal” country. Ireland’s insistence that it is not hostile to Israel per se conveys the impression that the oppression of the Palestinians is “some isolated error of judgment,” she writes. In truth, it has been “central” to Israel’s existence since 1948.

As well as correctly identifying Zionism as being the root cause of Palestine’s problems, Murphy is clear about what tactics should be used to try and defeat it. She is a strong supporter of the Palestinian call for boycott, divestment and sanctions against Israel. Isolating Israel is necessary, she believes, because its government and international backers are “allergic to talking honestly about justice as the basis for peace.”

Judging by this punchy and perceptive book, Murphy suffers from no such allergies.

David Cronin is a contributing editor with The Electronic Intifada. His book Europe’s Alliance With Israel: Aiding the Occupation is published by Pluto Press.