The Electronic Intifada 20 May 2004

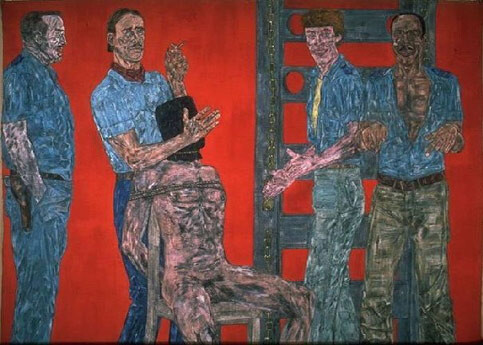

“Interrogation” by Leon Golub

When I saw the images of Iraqi prisoners being humiliated by U.S. troops in Abu Ghraib, I felt as though I had already visually experienced it in the visceral work of American artist Leon Golub. In the brutal imagery of Golub’s paintings, all too familiar figures appear: gun-toting mercenaries delight in the misery of those they torture; dogs snarl and threaten boxed-in prisoners. The painting “The Black Does Not Stop the Killing,” in which a pistol-wielding military man grabbing the arm of an unseen figure is partially blocked out by black paint, reminds us that media blackouts and ignorance of international affairs don’t mean that such violence ceases to exist.

Similar to what I sensed when first seeing the now infamous Abu Ghraib photographs, the even more recent images of house demolitions and death in Rafah incited an all too familiar feeling of dread — the feeling that we have seen this all before, and how horrible we are for letting it happen again.

Safely living in Chicago, I am enough removed from the suffering of the people in these photographs of Rafah and Abu Ghraib, that I can guiltlessly look to Susan Sontag’s recent book Regarding the Pain of Others. Sontag clinically, yet rightly, explains that “Something becomes real — to those who are elsewhere, following it as ‘news’ — by being photographed.” Of course, those in the photographs, and the masses of those who aren’t, have to live this reality every day, whether the rest of the world sees it or not.

Having read various humanitarian organizations’ reports on the treatment of those detained by the U.S. military in Guatanamo Bay, the U.S. military base that is illegally occupying Cuban land and holding those captured largely in the invasion of Afghanistan, it is not news to me that prisoners are systematically tortured in the name of a war on terrorism that is preventing anything but. Those snapshots of grinning U.S. soldiers and anonymous Iraqis could have just as easily come from Guantanamo Bay, or any of the other U.S. bases around the world that hold thousands of “enemy combatants,” “terrorist suspects,” or, as in the case of Abu Ghraib, those who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Sontag writes, “all photographs wait to be explained or falsified by their captions,” providing viewers with necessary geographical context. But because destruction in Palestine has become so commonplace, when we see the ruins of a cool white concrete house set off by the warm blue desert sky, with a family picking through the rubble for their possessions, those familiar with the conflict instantly recognize the landscape. As Amnesty International reported this week, “Over the last three and a half years, Israeli armed forces have demolished more than 3,000 homes, leaving tens of thousands of men, women and children homeless or without a livelihood.”

Refugees are made refugees for the second, third, or fourth time, while the political and academic elite worldwide quibble over whether these Palestinians have anything more than a symbolic right to return to their land and property seized in 1948, and again in 1967. So many photographs of bulldozed homes stream out of the Palestinian territories that Israel’s daily violations of international law are no longer news. Israel’s wall continues to be built on Palestinian land, separating farmers from their fields, students from their schools, families from their kin, Israelis from Palestinians — a literal manifestation of Israel’s iron wall philosophy detailed by Avi Shlaim in his history on how Israel has purposefully built up its military strength so it can coerce its neighbors into its own conception of peace.

One may argue that unlike the images from Rafah, it is because our own troops are pictured torturing and humiliating Iraqis that the Abu Ghraib photos have sparked such a controversy here in the U.S. But the line separating the U.S. military and that of Israel becomes dangerously blurred when considering that the Caterpillar bulldozers operated by the Israeli Defense Forces are manufactured in downstate Illinois, and that the U.S. military and many of the outside contractors occupying Iraq are borrowing Israel’s own “urban warfare” tactics for use in Iraq. Because the U.S. annually gives 30 percent of its foreign aid to Israel, a tiny sliver of a country with less than .001 percent of the world’s population, and one with more U.N. condemnations against it that Saddam Hussein was ever able to incur, it is impossible for Americans to say that we are not at all responsible for these crimes against humanity.

So maybe Sontag’s idea that photographs need to be explained by their captions to be understood is applicable to the imagery of destruction in Rafah after all. We won’t really understand the photographs until their accompanying text informs us that those are American-made bulldozers making Palestinians homeless again, Palestinians who have been enduring an American-funded dispossession and military occupation for 37 years.

“The Black Does Not Interrupt The Killing” by Leon Golub

While the U.K. and international media will prominently present the images of Rafah, Palestinian suffering rarely makes headlines in the U.S. Palestinian death statistics generally follow that of Israelis, even when higher. And reporting on how the Palestinians experience the conflict is all the more muddled in television news. Americans must actively seek out such images through the international and alternative press. And those knowledgeable Americans will have already been familiar with the story of occupation — they are not the ones who need the captions.

Of course, there is always the question of American apathy towards those who suffer, often as a result of misguided and immoral U.S. foreign policy. In a country where ignorance is bliss, our lives are designed to insulate ourselves from one another. We have automated checkout lanes at the grocer and ATMs to spare us time-hogging human interaction. We drive automobiles that resemble fortified tanks and armored vehicles more than they do cars, and insist on living in the largest single-family house we can afford, with as much land as possible separating us from our neighbors. Considering this lifestyle of personal partition, photographs of the suffering of others can only have so much impact.

It is utter indifference towards other human beings that allows for such atrocities like those in Rafah and Abu Ghraib to occur and to allow history to repeat itself. In his history King Leopold’s Ghost, Adam Hoshschild writes that during the turn of the last century Belgium’s King Leopold II, under the guise of humanitarianism, plundered the natural resources of the Congo, with 10 million Congolese losing their lives as a result.

Does the story sound familiar? It should. Under the guise of democracy and liberation, President Bush has invaded Iraq to exploit its natural resources and create a more dominant U.S. presence in the Middle East. Because the U.S. military has prevented even the Iraqi Governing Council from keeping records on Iraqi deaths, it is unknown exactly how many Iraqis have perished. Conservative estimates put the human cost at around 10,000 lives.

And as Americans have experienced with the war on Iraq, it wasn’t until Europe saw images of human suffering in the Congo that public opinion regarding colonial practice began to sway. Hoshschild writes, “A central part of almost every Congo protest meeting was a slide show, comprising some sixty vivid photos of life under Leopold’s rule; half a dozen of them showed mutilated Africans or their cut-off hands. The pictures, ultimately seen in meetings and the press by millions of people, provided evidence that no propaganda could refute.”

True, the photographs of destroyed homes and mourning families in Rafah don’t leave the same visual impact of pictures of Congolese children without hands or images of a woman U.S. soldier delighting in the forced masturbation of an Iraqi detainee. But we can’t wait for the photographs become much worse in order for public opinion and American policy towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to make its necessary change.

Related links

Maureen Clare Murphy, a recent graduate from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, is Arts, Music, and Culture editor for The Electronic Intifada and Electronic Iraq