The Electronic Intifada 27 October 2004

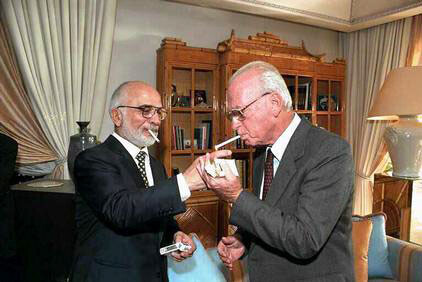

Jordan’s King Hussein and Israeli Prime Minister Yithak Rabin enjoy a cigarette shortly after the signing of the peace treaty between their two countries, 26 October 1994

Few things united Israelis more than their desire to sign a peace treaty with Jordan. The agreement signed at a spectacular ceremony in Wadi Araba on Oct. 26, 1994, was meant to mark the beginning of a new era of formal peace and prosperity (formal, because a de facto state of peace had long existed between the two neighbours). That historic achievement was the first and most tangible fruit of the Madrid process launched three years earlier. The Oslo accord was not a Madrid product.

King Hussein was a great believer in peace, and during his long rule he never wasted any opportunity which he thought would bring the region closer to peace. “I will never leave one stone unturned in my search for peace,” he often said. As my country’s ambassador to Italy, on Oct. 16, 1994, I arrived in Amman accompanying an Italian delegation headed by then Foreign Minister Antonio Martino. The next day, it was officially announced that a successful session of Jordanian-Israeli negotiations that lasted for most of the previous night, with King Hussein and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin heading their respective delegations, had ended in agreement on all outstanding issues, marking a major breakthrough and paving the way for signing a peace treaty between the two countries ten days later.

When the King received the Italians, who were there for a different mission, and later invited them to lunch, he expressed his greatest happiness for the grand achievement. He was highly contented and clearly fulfilled. At lunch, he spoke elaborately about peace, its unlimited benefits, and how it will radically change the region. He spoke of the years lost in confrontation and conflict, saying with clear satisfaction that “it is high time that they are now over”. And he stressed that “they kept telling us that peace was not achievable and here we prove it is, for us and for the generations to come”.

King Hussein reflected Jordanians’ genuine desire to achieve peace, one that we remain committed to despite all the disasters that have struck the region since. Israel, by contrast, seems determined to reduce its treaties and agreements with Egypt, Jordan and the PLO to nothing but worthless pieces of paper. It’s unrelenting aggression and bad faith are entirely responsible for the growing hostility it is experiencing in the region and the world.

Jordan saw its peace treaty, like Israel’s agreements with the Palestinians and Egypt, as necessary steps towards the comprehensive regional peace envisaged at Madrid, supported by all Arab states and called for by UN resolutions. Israel, however, seems to view these agreements as tools to strengthen itself at the expense of its neighbours. For that reason, Israel never wanted to negotiate with the Arabs collectively, insisting instead on taking them one by one, believing that by isolating each state, it could secure the best terms and then use any precedent set for negotiating with the next. This method was successfully used in the 1949 armistice talks and Israel has pursued it ever since.

It is quite evident that the resolution of the “Arab-Israeli conflict” requires an “Arab-Israeli peace”. If the Arabs, under the pressure of unhelpful circumstances, and mainly due to Israeli opposition, had to abandon their collective approach to negotiations, they never abandoned their goal of comprehensive peace, even if they hoped to achieve it gradually.

When Egypt’s President Sadat embarked on his daring initiative to make peace with Israel, he struggled hard to avoid a bilateral treaty, in favour of establishing a framework for simultaneous agreements on the Syrian, and the Jordanian/Palestinian sides. His effort was bitterly resisted by Israel which failed to seize the historic opportunity to engage its Arab neighbours in a true search for a just and an honourable peace, which all the people of the region would be enjoying now. Apparently, Israel had a different agenda altogether, aiming to exploit the Egyptian overture in the worst possible manner by trying to isolate Egypt from the rest of the Arab world. Israel never wanted the Egyptian peace to be the beginning of a process. Rather, peace with Egypt was supposed to end pressure on Israel to withdraw from other occupied Arab territory.

Israel’s withdrawal from Sinai was meant to enable Israel to stay in the West Bank and Gaza forever. That strategy failed, but Israel is trying it again now, hoping that its plan to “disengage” (Israel never uses the word withdraw) from Gaza will still allow it to hold on to occupied Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank. The motivation in Oslo was similar: impose a meaningless agreement on a totally incapacitated and desperate partner to preempt the demand for a real agreement.

We should remember that the Palestinian-Israeli accords, which were signed a year before the Jordan-Israel treaty, were the product of Oslo, a totally different process from that in Madrid. The secret Oslo channel was designed to circumvent and sabotage the Madrid process. Through Oslo, the Israeli “moderate left” sought to exploit the desperate quest of the isolated Palestinian leadership for formal recognition in the peace talks (the Madrid process allowed the PLO only an indirect, unofficial role). Israel traded its mere recognition of the PLO for substantive concessions from the Palestinian side, including full recognition of Israel and a renunciation of armed struggle.

While receiving the Palestinian payment in advance, Israel refused to recognise Palestinian statehood and maintained the “right” to continue to enforce occupation and colonisation through violent aggression against the Palestinian people, which it did with escalating brutality throughout the Oslo years.

There is hardly a precedent in history where a conflict of such magnitude and complexity was declared settled by an agreement which deferred, for years, even the discussion of the fundamental causes of the dispute. It was much like declaring the victim of an accident cured and permitting him to resume normal activity, on the “promise” that his broken leg would be treated five years later. Worse still it would be if the doctors sought to gain the patient’s confidence, and to make him feel better, by continually administering hammer blows to the injured limb.

In the same manner, Israel and the PLO celebrated the end of their historic struggle by deferring all final-status issues, which constitute the core of the dispute — occupation, the rights of refugees, Jewish colonies and the status of occupied Jerusalem — for later consideration. Anyone who dared raise objections, or who pointed out the absolute absurdity of conducting “negotiations” while Israel was busy stealing and settling as much land as it could, was marginalised and branded an “enemy of peace”. Suffice it to remind that the result, eleven years since Oslo was celebrated worldwide, is that the conflict is far more complicated, with the two sides locked in the bloodiest and cruellest violence, with no prospect for any possible exit in the foreseeable future.

It is logical in the light of all the above to deduce that Israel sought its treaty with Jordan also as a means, rather than an end; a means to tighten its stranglehold on Palestine and the Palestinians, to facilitate the ongoing process of colonisation and Judaisation. How could it be possible, otherwise, to understand why Israel has, for over ten years now, blocked any positive functioning of the treaty, leaving the worst disappointments to flourish and to render the historic achievement a dead letter?

It is hard to comprehend how Israel fails to see that it can never enjoy warm peace with one Arab country while it continues to occupy and butcher people in others, or that any peace agreement imposed from the top, without engaging the people and offering them justice and dignity, without rightly resolving the components of the conflict, can ever work. Israel’s behaviour is not consistent with a desire for peace, but with an unquenched appetite for land acquisition and expansion.

Ten years after the Jordanian-Israeli treaty provided such hope, the Zionist experiment in Palestine is in more trouble than it has ever been, and Israel is running into a dead end of its own making. On this sombre anniversary, the Israelis should ask their leaders why they never missed an opportunity to miss all the opportunities for peace that their neighbours have repeatedly offered them.

Ambassador Hasan Abu Nimah is former permanent representative of Jordan at the United Nations and was a member of the joint Jordanian-Palestinian delegation at the Washington Peace Talks in 1992-93.