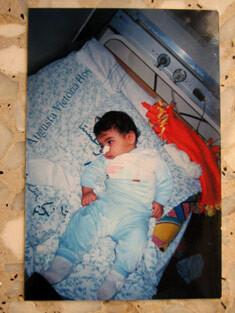

A photograph taken of nine-month-old Mohammed in the hospital after being gassed.

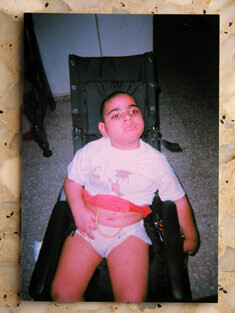

A recent photograph of Mohammed.

Five years ago, nine-month-old Mohammed and his grandmother were in their West Bank home when it began to fill with nerve gas from a nearby Israeli Occupation Forces military base. The army had moved in on a hill near their home in the Skan Abu Absa suburb of Ramallah, and would frequently shoot all over the surrounding area, often retaliating against Palestinian gunfire from a hill away from the suburb. As the gas seeped into his living room, the baby Mohammed began to shake violently before suffering a stroke causing extensive paralysis. His grandmother ran to pick him up and also inhaled the gas, causing an intense burning sensation all over her body. When she realized her grandson had stopped moving, she pleaded with the soldiers outside to open the road out of her town and raced Mohammed to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with severe neurological deterioration resulting in a vegetative state. The Palestinian Ministry of Health and UNRWA conducted extensive tests on Mohammed and his parents to determine with certainty the cause of his condition. After a full genetic investigation, doctors confirmed that Mohammed’s state was neither hereditary nor due to a chromosomal abnormality, but a result of the poisonous gas.

I met Mohammed’s father Sami waiting at a checkpoint near Haris. He’d hesitated to publicize his son’s story for fear of harassment from the army. He said his family was suffering enough — their personal tragedy only began with the gassing. After Mohammed’s injury, Sami’s father went from being a strong healthy 47-year-old to an emotional and physical wreck, and died one year later from stress and heart problems. Mohammed, now six, continues to suffer from severe neuro-developmental delay, poorly controlled seizure disorder, the loss of sight, and inability to eat normally. He eats via a G-tube (poking directly into his stomach) and is fed a special formula “Pediasure” that is not available in Israel/Palestine, so Sami travels to Jordan every three months to bring the formula and anticonvulsants that Mohammad requires. Each time Sami crosses back to the West Bank, he is forced to pay Israeli customs taxes on the formula, totaling hundreds of dollars a year. This is in addition to countless other expenses: land travel, adult diapers, maintaining his customized bed (to prevent bed sores), medicine, and round-the-clock care. Sami and his wife spend so much money taking care of Mohammed that they lack the remaining funds to take legal action against the Israeli Army for poisoning their son.

Tragic stories of Occupation-induced paralysis are common in the West Bank, so even if Mohammed’s family had the money for a lawsuit there’s little reason to believe it would be remarkable enough to bring the Israeli Army to justice. I recently interviewed Moussa, a young paraplegic who lost the use of his legs five years ago at the age of 19 when the army shot him in the colon. One Monday in February, Moussa began experiencing severe pain from an infection in his wound, which a Red Crescent doctor warned could become systemic if not treated immediately. The infection risked reaching the bones in Moussa’s back, developing gangrene, and poisoning his blood, but even the best West Bank hospitals had sent him home because they were ill-equipped to treat such a serious condition. On Tuesday, Moussa’s doctor referred him to a hospital in Jordan, and in two days the family renewed Moussa’s passport and obtained a transfer from the Palestinian Ministry of Health to receive treatment in Amman. Then on Thursday, as the family was preparing to leave, Israel refused the sick wheelchair-bound young man permission to leave the West Bank for unspecified “security reasons.” When Moussa’s doctor explained that waiting could mean the difference between life and death, the Israeli DCO invited the family to appeal the decision, but only three days later, after the Jewish Sabbath.

We put Moussa’s family in touch with Physicians for Human Rights, who were successful in getting him to Jordan before his infection could become fatal. But Moussa will still never walk again, nor will my neighbor and friend Issa, who shot by soldiers outside his home in May 2001 as he ushered children in from the streets during an army invasion. In spite of his handicap, Issa remains committed to working nonviolently against the Occupation. Last time we spoke, he quoted an Arabic saying: “You can’t clap with one hand.” He said Jews, Palestinians, and the world must work together to end injustice and oppression everywhere.

Almost three years ago, Issa wrote an open letter to the two anonymous soldiers who shot and paralyzed him. It was published in Haaretz and elsewhere, and I’ve copied it below. It is worth reading:

I remember you. I remember your confused face when you stood above my head and wouldn’t let people come to my aid. I remember how my voice grew weaker, when I said to you: ‘Be humane and let my parents help me.’ I keep all those pictures in my head. How I lay on the ground, trying to get up but unable. How I fought my shortness of breath, which was caused by the blood that was collecting in my lungs, and the voice that was weakened because my diaphragm was hurt. I won’t hide from you that despite this, I had pity for them. I felt that I was strong, because I had powers I didn’t know about before.Issa is Arabic for Jesus, who is also revered as a prophet in the Muslim faith. Some would say it’s a suitable name for a man who believes in responding to injustice with passionate nonviolence and forgiveness. Mohammed and Moussa (which means Moses, also a prophet in Islam) never wrote a letter like Issa’s, but they and their families welcomed me, a Jewish American, into their homes with gentle kindness and openness. Struggling for peace and survival in spite of great personal tragedies, the three prophets’ namesakes and their families, like so many Palestinians paralyzed physically (as well as emotionally, spiritually, and economically) by the Occupation, are some of the true — albeit often forgotten — heroes of Palestine.That was exactly three years ago. I rushed out of the house in order to distance the village children from the danger of the teargas. They were used to playing their simple games on the dusty streets of the village while the pregnant women watched over them and chatted. I didn’t believe that your weapons contained live bullets or dum-dum bullets, which are prohibited under international law. I was able to protect the children and get them away from your fire, and I don’t regret that.

I pity you for having become murderers. Since I was a boy, I have hated killing, hated weapons and hated the color red, just as I hate injustice and fight against it. That is how I have understood life since I was a boy, and that, in the same spirit, is what I have taught others. I gave all my strength for the sake of peace and justice and for reducing the suffering that is caused by injustice, whatever its origin. Yes, I pitied you, because you are sick. Sick with hate and loathing, sick with causing injustice, sick with egoism, with the death of the conscience and the allure of power. Recovery and rehabilitation from those illnesses, just as from paralysis, is very long, but possible. I pitied you, I pitied your children and your wives and I ask myself how they can live with you when you are murderers. I pitied you for having shed your humanity and your values and the precepts of your religion and even your military laws, which forbid breaking into homes and beating civilians, because that undermines the soldier’s morale, his strength and his manhood.

I pitied you for saying that you are the victims of the Nazis of yesterday, and I don’t understand how yesterday’s victim can become today’s criminal. That worries me in connection with today’s victim — my people are those victims — and I am afraid that they too will become tomorrow’s criminals. I pity you for having fallen victim to a culture that understands life as though it is based on killing, destruction, sowing fear and terror, and lording it over others. Despite all that, I believe that there is a chance for atonement and forgiveness and a possibility that you will restore to yourselves something of your lost humanity and morality. You can recover from the illnesses of hatred and the lust for revenge, and if we should meet one day, even in my house, you can be certain that you won’t find me holding an explosive belt or concealing a knife in my pocket or in the wheels of my chair. But you will find someone who will help you get back what you lost.

You will find a soft and delicate infant here, whose age is the same as the second in which you pulled the trigger and who will never see his father standing on his feet but who is full of pride and power, even if he has to push his father’s chair, having no other choice. Even though I have reasons to hate you, I don’t feel that way and I have no regrets.

-Issa Suf, 15 May 2004; the third anniversary of my being wounded

Anna Baltzer is a volunteer with the International Women’s Peace Service in the West Bank and author of the book, Witness in Palestine: Journal of a Jewish American Woman in the Occupied Territories. For information about her writing, photography, DVD, and speaking tours, visit her website at www.AnnaInTheMiddleEast.com