The Electronic Intifada Beirut 18 September 2014

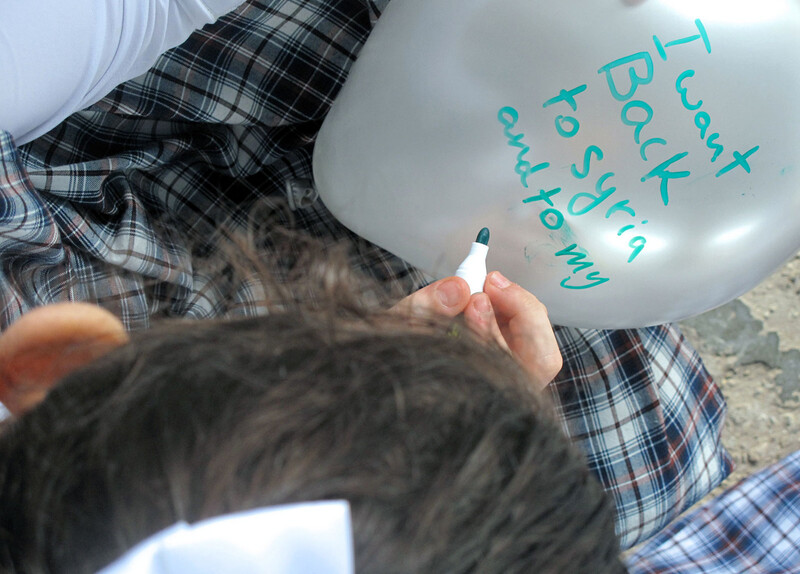

A Palestinian refugee girl from Syria writes her wish for the future during a psychosocial support activity organized by UNRWA in April 2014.

UNRWAOn Tuesday, 9 September, Palestinian refugees from Syria descended from across Lebanon to Beirut. They gathered in a group of approximately two hundred to protest outside the UN refugee agency UNHCR’s headquarters in the capital’s Jnah neighborhood.

The protest was called by Syria’s Palestinians in Lebanon, an organization that draws attention “to all the humiliation and insults” they are subject to in Lebanon.

At the protest, Palestinian refugees described the dire conditions they face in Lebanon.

A middle-aged man, Omar, stood warily on the sidewalk facing the UNHCR building. A resident of Yarmouk refugee camp near Damascus, which has been under siege since June 2013, Omar was sandwiched between his teenaged son and daughter. He held onto his family in the absence of his wife who he said was “taken by death in Yarmouk last year.”

Omar explained that “it’s very difficult for a father to support his family.” Then he went silent.

He began to grow uncomfortable as his son and daughter looked at him from both sides, waiting for him to continue. The widowed father’s sleep-deprived eyes broke into tears as he spoke again.

“We don’t know what to do,” he said. “We’ve lost everything in Syria and we can’t return to Yarmouk. No one wants to help us; we can’t stay in Lebanon.”

Firm demands

Palestinian refugees from Syria came to the protest with a list of demands they delivered to UNHCR representatives. The demands include lifting the ban on renewing residency permits for those who have been in Lebanon for more than a year; ending forced deportation; lifting the closure of the Syrian-Lebanese border; addressing the lack of adequate financial support from UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestine refugees; and securing the right to asylum in European countries.

Tarik Sakhnin, 23, was studying journalism at Damascus University before he fled to Lebanon two years ago. He told The Electronic Intifada: “This is not a protest. This is us trying to confront the world, trying to say we are here we are living in hard times. We are here because we refuse to die silent.”

Sakhnin said that Palestinians from Yarmouk and other refugee camps in Syria want to return to Palestine, not to “the unknown of today’s Syria.”

Most Palestinians in Syria are refugees from the 1948 ethnic cleansing of Palestine and their descendants. Israel refuses to respect the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their land and property.

“The majority of us came here today in the hope we can get the right to apply for asylum to Europe, and once we get a European passport, we want to return to Palestine,” Sakhnin added.

The severity of circumstances Palestinians have experienced has pushed many to take desperate measures in hope of a better life, including undertaking treacherous journeys by small boats to other countries across the Mediterranean.

“Many of us have nothing left to live for in life so we take the only option available now, we go and take death boats, risk it all and hope we get to Europe alive,” explained Sakhnin.

The plight of Palestinian refugees from Gaza and Syria came to the fore in recent days. Approximately five hundred refugees, many of them Palestinians, were drowned during the deliberate sinking of a vessel by human traffickers in the Mediterranean.

Subjected to violence

Refugees from Syria sheltering in Lebanon have been subjected to public, violent resentment from Lebanese citizens as well as raids in which security forces look for the most trivial pretext to attack, arrest or deport people back to Syria.

The violence in Syria has impacted Lebanon. Most recently, Lebanese soldiers have been captured by the group Islamic State in the town of Arsal, close to Lebanon’s border with Syria, in multiple incidents over the past two months. There has also been fighting between the Lebanese army and the Islamic State in the Bekaa Valley, where Arsal is located.

Um Muhammad, 48 years old, is another Palestinian refugee to have fled Syria. She and her family have been living in Lebanon’s Rashidieh refugee camp for the past two years.

“In Rashidieh, there is no security or safety — my six girls and only son and I live in a garage,” she said. “We pay a monthly rent of $100 and another $50 for electricity.”

She explained that they are forced to search for food every day, foraging for edible plants to eat.

“A Palestinian mother will have to come up with a miracle,” she added, to nourish her family under such circumstances. Throughout the month of Ramadan earlier this summer, Um Muhammad said that she only received one portion of food aid which only lasted a few days, and UNRWA stopped giving her family financial aid to pay their rent.

“Our people, those political factions in the camp, are against us,” she said. “They raised the rent for everyone and then turned to us and blamed us. They said, you Syrians raised the prices, and so in turn, Palestinians from Lebanon believe that it was us who made their situation worse than it was.”

Deprived of education

Um Muhammad’s children will not be going to school this year. This is the second school year they have missed.

The Lebanese education ministry announced recently that priority will be given to Lebanese children. The other 400,000 non-Lebanese pupils will have to wait and see if there will be available teachers and seats in government-run schools.

According to UNRWA, more than 53,000 Palestine refugees from Syria were seeking safety and shelter in Lebanon in April this year. Most of them have gone to the coastal city of Saida and to refugee camps further south.

Some Palestinians who fled from Syria now residing in Shatila camp in Beirut live inside garages and pay a steep rent of up to $400 a month for such inadequate spaces.

“Dilemma”

According to one international aid worker who operates relief programs in the south of Lebanon, Palestinian refugees from Syria have been excluded from the relief programs funded by UNHCR.

“One day last winter, we were distributing winter kits [containing thick blankets and mattresses] at the area of distribution for Syrian refugees,” said the worker, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“Our team was approached by two Palestinian families from Syria,” the aid worker recounted. “They were obviously eligible to get a kit, but our team leader was faced with a moral dilemma: UNHCR provides us with data of beneficiaries from the program and those two families were not listed because they are [Palestinian refugees from Syria]. We knew if we gave them kits and listed them as additional beneficiaries, UNHCR might stop our funding and we would all lose our jobs. Finally, we decide to give both families kits without listing them.”

UNHCR is only mandated to offer relief to Syrians fleeing from Syria, and not Palestinians, even though they are fleeing the same war.

Majida is a 34-year-old schoolteacher and mother of three who once had her own two-bedroom apartment in Yarmouk. Today, she shares a one-bedroom apartment with her brother-in-law and his family in Saida refugee camp.

“My three children and I risked deportation by coming here [to the protest] today. Our residency permit expired last year and if we are stopped at a checkpoint we will get deported back to Syria,” she said.

Majida bitterly denounced the favoritism that influences decisions about which families receive aid. She said that some families who know aid workers or who are affiliated with certain political parties receive monthly help.

“I am not going to beg this or that man from the political parties,” she exclaimed. “We will not die from hunger … We are forced to be in Lebanon in exile — it is not as if we are here on a vacation.”

Moe Ali Nayel is a freelance journalist based in Beirut. Follow him on Twitter: @MoeAliN.