The Electronic Intifada 8 May 2018

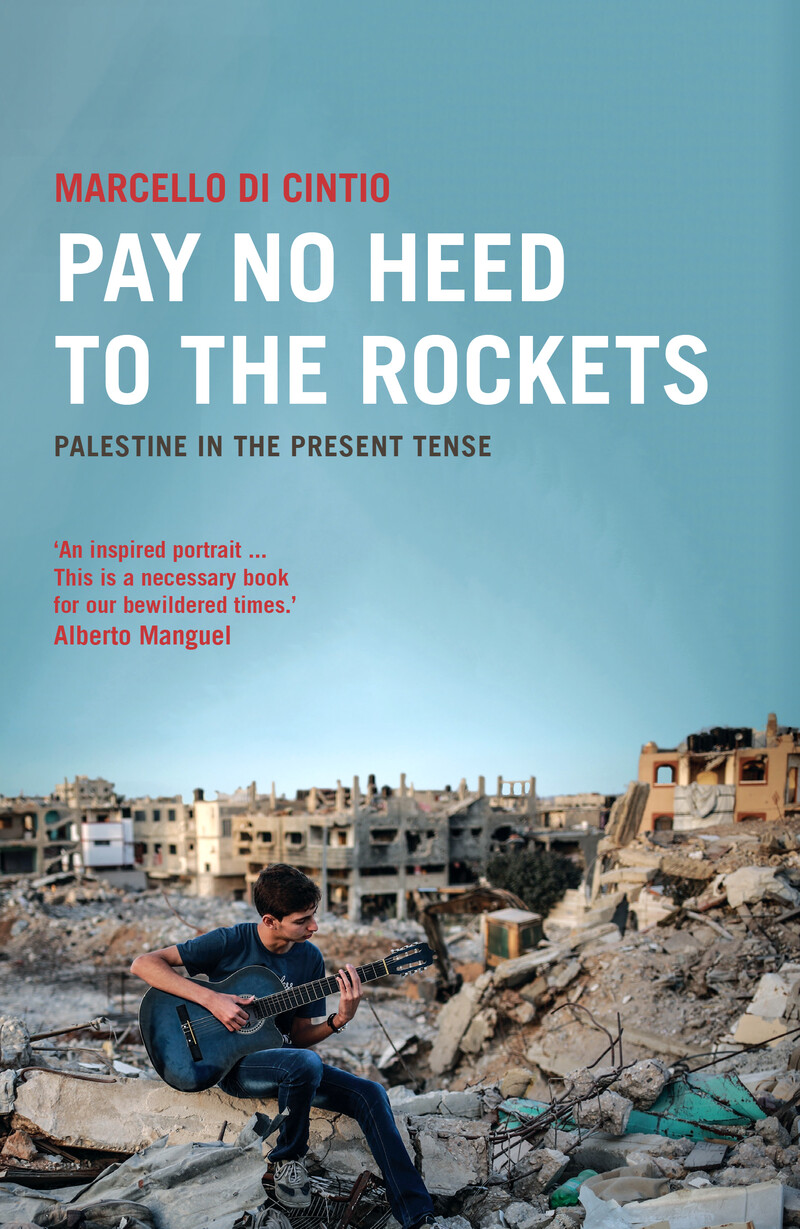

Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense by Marcello Di Cintio, Saqi Books (2018)

One night in May 2010, following Gaza police interrogation, actor and theater impresario Jamal Abu al-Qumsan phoned all the human rights activists and foreign journalists he knew in Gaza and told them to meet him in two hours at the Gallery café that he ran.

When they arrived, he disclosed his intentions: “I invited you all here to photograph my arse,” he stated, after which, according to author Marcello Di Cintio, “Jamal turned and dropped his pants for the assembled media.”

The red welts on his buttocks received from the beating at the police station had, by this point – as he had calculated – turned blue, purple and green. “It was like a painting,” al-Qumsan noted. The photo later went viral “In Japan, China, Italy, Morocco, Sweden. Even on porn sites you would find photos of my arse.”

Di Cintio’s Pay No Heed to the Rockets is filled with accounts similar to al-Qumsan’s, where the stories are so engaging and well written that it makes the cruelty that is referenced all the more shocking, due to the admiration and amusement that the protagonists are still able to inspire.

The right to be frivolous

There is an irreverence, individualism and self-possession to all of the writers that springs from the pages. These are sensitive characters living in abnormal conditions.

Di Cintio writes with clarity and grace and there’s a meandering chronological development in the book – from early and mid-20th century poets such as Fadwa Tuqan and Mai Ziadeh to present-day authors – told through excerpts and interviews as Di Cintio moves from the West Bank to the Gaza Strip, with the thematic focus of chapters revolving around various authors’ works.

How the authors were selected for inclusion by Di Cintio is not always clear. Sometimes, it seems, a writer is included simply because they were bumped into in a cafe or via a friend. But by keeping the criteria for selection loose, Di Cintio is able to introduce the words and works of more obscure Palestinian writers as well as highlight the lesser-known aspects of the lives of more established authors.

The writer Maya Abu-Alhayyat is well aware of the toll exacted by the political situation in which Palestinian writers live: “We all have mental disease because of everything that happened in our history as Palestinians. The whole thing makes us ill.” Writing can be both an exploration of and a balm for this disease.

Many of the writers interviewed are also sick of being othered by the Western gaze and made into subjects of study. “I want to be a writer,” the Gazan Asmaa al-Ghul pronounces forcefully to Di Cintio, “I don’t want to be a topic.”

It is early on in his visit, while staying in Ramallah, that Di Cintio becomes aware of this love-hate relationship with the Western audience. In the smoky artists’ hangout Café Ramallah (itself eulogized by poet Moheeb Barghouti), a woman asked him “flat-out how [he] would ‘avoid being an Orientalist,’” to which Di Cintio concedes that he “didn’t have a good answer.”

More so than in any other group of writers, Palestinian authors have had to constantly weigh their role in society and where they stand as political agents. Even to devote oneself exclusively to “art” is an overt political statement.

The debate is alive and ongoing. Di Cintio muses on the generational shifts it has taken. He wonders if “Gharib Asqalani represents the first generation of Palestinian writers, who wrote in the service of the nationalist cause, and Atef [Abu Saif] represents the second generation, who traded nationalist symbols for the details of a regular Palestinian life,” and whether “Rana [Mourtaja] represents the next generation: men and women who are not compelled to portray Palestine at all.”

This debate is not new. Its parameters were set by Mahmoud Darwish who expounded on the need for Palestinian literature to “explore metaphysical themes like love and death and liberate itself from an airless preoccupation with politics and oppression.” He went on to demand the right for Palestinian writers to be “frivolous.”

Di Cintio asks writer Rana Mourtaja if she feels any responsibility to write Palestinian stories, to which she makes an interesting distinction: “I feel a responsibility to the people,” she replies, “not to the cause.”

Resisting occupation and categorization

Di Cintio’s gaze is kind and steady and he portrays the included writers with modesty and empathy, while missing little by way of telling detail. He records, for example, how, when he visits the author Gharib Asqalani’s house in Gaza with his interpreter, Lara Aburamadan, they are offered coffee, but it is Aburamadan who is directed to the kitchen to make it.

The request causes her to shoot a look of “bemused irritation” to Di Cintio before going off to dutifully make the coffee. The soft-spoken Aburamadan, at 23, “is already a professor of war,” Di Cintio writes, who can identify “Israeli ordnance by the different way the ground shakes after each explosion.”

Di Cintio manages to record the foibles of these writers – who are, after all, artists – without judgment. For example khulud khamis stipulated that her name should appear uncapitalized, while Moheeb Barghouti flamboyantly dons broken glasses, a fedora, a red beard and gray t-shirt printed with the image of the Persian poet Rumi.

Di Cintio displays an underlying respect toward his interviewees; these are creative individuals whose lives have been challenged by more experiences than most Western writers. He’s willing to allow them their eccentricities and appreciates their desire to spar.

There is also the pitch-perfect capturing of Palestinian humor in Di Cintio’s book, something rarely caught by dour journalistic reports. This is humor used as a defense mechanism, a societal glue and a coping tool for the overwhelming injustices that people are forced to endure.

The dignity of stoic understatement, for example, is conveyed when Wisam Rafeedi describes his time evading arrest from the Israeli authorities. Rafeedi, who ended up living in hiding for almost two years, part of which was spent “alone in the dark for five months” in a safe house.

His only contact with the outside world was that “every two weeks someone came and put food outside the room, knocked a secret signal and went away. … It was not a good house.”

Emotional vivacity

Pay No Heed to The Rockets is not the first book on Palestinian writers and the Palestinian literary scene. It follows on the heels of Bidisha’s Beyond the Wall: Writing a Path Through Palestine (2012) as well as the more recent Palestinian Festival of Literature publication, This Is Not A Border, edited by Ahdaf Soueif and Omar Robert Hamilton (2017).

This book has a different objective to the works mentioned above. Di Cinto’s focus is specifically on writers he meets. It is a more in-depth account of the experiences of Palestinian writers and their literature than those captured by the PalFest participants, who normally visit Palestine for shorter periods. Di Cintio places these writers in their historical contexts and reads and researches the writers interviewed at length before meeting with them.

Even for a reader familiar with Palestinian literature, Pay No Heed to The Rockets uncovers stories from the past with emotional vivacity – for example, Darwish’s childhood – and brings to life more vividly than other, often rather dry accounts I’ve read, the lengths to which prisoners went in order to educate themselves and others, and to write.

Di Cintio weaves together history with a sense of place and infuses character with dialogue and humor to produce a contemporary portrait of a people who continue to resist both occupation and simple categorization in this masterful work.

Selma Dabbagh is a British-Palestinian writer. Her debut novel, Out of It, was published by Bloomsbury (2012).