The Electronic Intifada 6 April 2015

Baddawi by Leila Abdelrazaq (Just World Books)

Baddawi, the debut graphic novel by Leila Abdelrazaq, is a coming-of-age story centered on a boy named Ahmad, whose parents are originally from the Palestinian village of Safsaf. The atrocities of the Nakba — the 1948 ethnic cleansing of Palestine — force them to flee to Baddawi, a refugee camp in northern Lebanon, where Ahmad is born.

Tellingly, “Baddawi” is derived from the word “Bedouin,” or nomad. The short chapters that comprise the book run the gamut of childhood stories not unlike those of any young boy to stories of death, extreme violence and the desperate attempt to live life anyway.

Abdelrazaq based this work on the early experiences of her father, and modeled the protagonist after him. This is made especially poignant by the inclusion in the back pages of family photographs including photos of her father and one of her grandparents from the 1970s.

Abdelrazaq’s best work is in her conceptual visuals, which often lend themselves well to the material. One particularly strong example is when the reader is shown Ahmad’s grandfather’s daily ritual of grazing his three sheep in a nearby refugee camp.

This is done in three closely-knit panels. The first portrays a bare scene; below this is a close-up of the grandfather’s opened eyes. In the second panel, the scene is populated with a large number of sheep; there is also a patterned border around the panel and the grandfather’s eyes are now closed, suggesting that this is a memory of more plentiful times. In the final panel, the multiple sheep are whittled down to three, grazing next to a ruined wall; his eyes are again open.

Patterns — specifically ones used in tatreez, or Palestinian embroidery — are scattered throughout the book, incorporating things of beauty in sometimes dire circumstances.

Shadowy armies

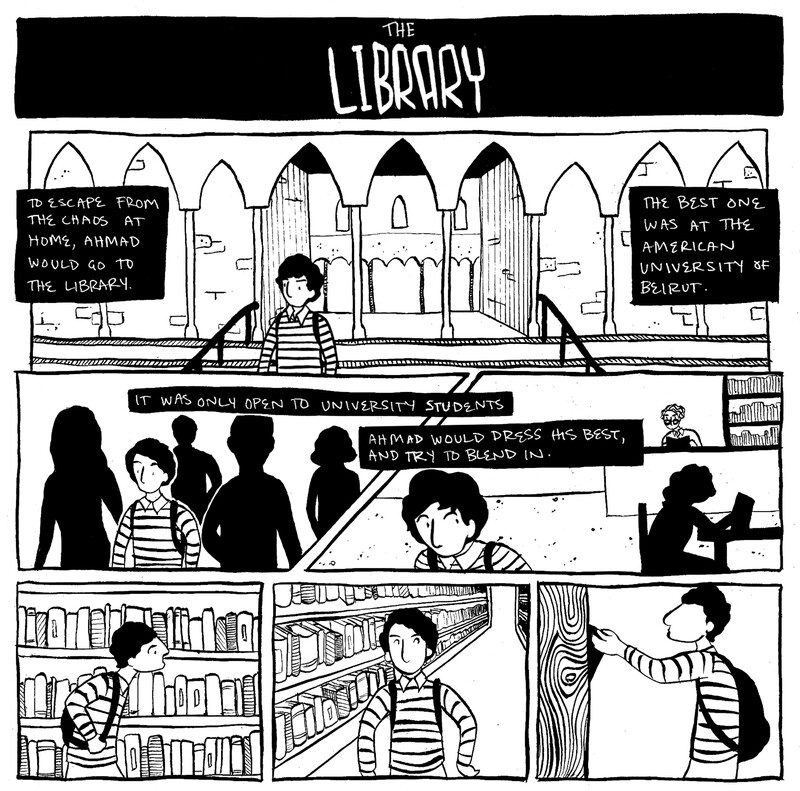

From Laila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi.

Baddawi is filled with such conceptual storytelling and makes heavy use of silhouettes. This serves multiple purposes in the story — to portray anonymity, silence and violence in a non-gratuitous way. The silhouettes are also used to suggest, but never actually show, aggressive forces like the Israeli and Lebanese armies, who are spectral in nature or are only witnessed through the aftermath of their destruction. They are depicted, for example, as an angry ocean, brandishing guns, in one scene recounting a joint Israeli-Lebanese militant raid on Baddawi camp.

In a later scene, after Israeli special forces raid a Beirut building to kill members of the Palestine Liberation Organization, the reader is shown the evidence of the event — bullet holes in the walls, blood on the floor. There is no attempt to rationalize or humanize military forces in this book.

Some storytelling elements, however, are muddled or less effective. In the opening chapters it is established that the Lebanese army headquarters in Baddawi is an imposing, well-kept structure that figures heavily in Ahmad’s imagination. The army eventually leaves the camp and abandons its headquarters, leading Ahmad and his friend to scale the fence and finally catch a glimpse of the inside of the building.

While the reader is treated to a full-page view of what the two boys imagine the interior to be — with decorative carpets, a chandelier, and curving staircases — the following page depicts the actual state of the building, described as “a dump” by Ahmad. This drawing is in a rather small panel with a few cracks in the walls and a dirty carpet to signify its ruinous state.

The moment is meant to be a payoff — the headquarters are built up to almost mythical proportions in the eyes of the children. I would have loved to have seen this room in complete disrepair and given the same detail as the imagined room on the previous page.

Refugee life

From Laila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi.

The themes of the short chapters vary throughout the book and are insightful in their reflections on refugee life, both in Baddawi and in Beirut, where Ahmad travels on many occasions. While the plight of Palestinian refugees is something that is rarely addressed in comic book form, and giving the subject the gravitas it deserves is important, it’s also equally important to use the platform to allow the characters to transcend symbolism. Ahmad is no longer the faceless Palestinian refugee caught in a human rights dilemma; his aspirations and mistakes are laid bare for the reader.

Abdelrazaq has done a fantastic job of balancing Ahmad’s personal life against the greater context of the occupation. Some of the stories told are simply stories of Ahmad’s growing up. In one chapter, for example, Ahmad and his sister take their younger brother Afif to the hospital after he injures his arm on the way to school. This scene is not political in itself, though Ahmad takes the opportunity to talk to his sister about the Lebanese school he now attends, comparing it to the refugee school in Baddawi. Ahmad’s family’s refugee status and all it entails remain in the backdrop.

Other chapters not only speak of the political and social upheavals and wars happening at the time, but how these personally affect Ahmad, his family and his friends. While comics exist that discuss the Palestinian experience in a more personal way — the best-known being Joe Sacco’s Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza — there is no work in English, as far as I know, that speaks of the plight of Palestinian refugees, follows the same family while doing so and individualizes the family in that the stories describe more than warfare and struggle.

This is a rare chance for the English-speaking public to look in on a people who are infamously highly politicized and marginalized, and for that, the comic is invaluable. While it is not, then, without technical problems, it is nevertheless a unique and necessary voice, especially in the world of comics.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this review referred to color family photographs at the end of the book and of a scene of Ahmad injuring his foot. Both references have since been omitted after being informed by the publisher of changes made to the book after the release of an advanced review copy.

Marguerite Dabaie is a Palestinian-American illustrator and cartoonist based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work can be found at www.mdabaie.com.

Images courtesy of Just World Books.

Comments

where can I buy this?

Permalink johnnydee replied on

Hi Ali, can you provide a link to a place I can buy this? A quick search of the artists site, I couldn't find it. Cheers. Johnnydee

How to buy "Baddawi"

Permalink Helena Cobban replied on

Buy it here: http://t.co/x5IwsQvRDg!