The Electronic Intifada 16 March 2004

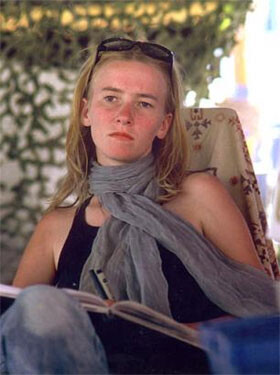

Rachel Corrie at the Burning Man festival.

But injustice in Palestine does not end in Palestine and justice in Palestine does not start there; it starts and ends within us. Injustice as disparity based on what the political philosopher, John Rawls, once called “the natural lottery” is strikingly present in many of our own relationships to those suffering in Palestine and indeed to most others in this world. As Americans, we are in possession of innumerable privileges in resources, land, leisure time and freedom, not principally on the basis of ethnicity or religion, but on the basis of no less fortuitous conditions of nationality and domicile.

To be aware of this privilege is the first step in understanding and achieving justice. To dismantle this privilege is to actually begin to achieve it. For doing justice in the context of this global system of opportunity for some and its absence for others is to actively reverse the system. It is to reject personal privilege as part of the process of rejecting institutionalized social, economic and political privilege. Justice is the act of renouncing some of one’s own advantage, be it money, resources, leisure time or freedom, so that those without might have them. It is to make the world more equal by making one’s own relation! ship with the underprivileged less unequal, thereby bringing equality into existence. Justice, like peace, is surpassingly a condition lived, not merely pursued—or, more properly, lived in its own pursuit.

Encouragingly, everyday, more and more individuals are rejecting privilege in justice’s pursuit. Their choices are the outcome of a trinity of modern information technology, greater access to economic security and career choice and the basic human sentiment of empathy and adherence to the ideals of equality and liberty.

Technology has offered the world’s privileged classes increased exposure to the enormous human suffering that exists in this world. Though the mass media’s uncritical posture, narrow perspective and sophomoric choice of topics to report on (from Joey Buttafuco’s shenanigans, to the endless O.J. Simpson trial, to the Nancy Kerrigan fiasco, to the Monica Lewinsky scandal, to the various other episodes of local and personal mischief transformed into international incidents) acts as a form of censorship of this tremendous suffering, with the rise of the Internet and modern information technology more generally, fewer and fewer individuals, particularly in post-industrial societies, can credibly claim ignorance about the plight of suffering human beings all across this planet.

Complementing this information has been the emergence of a broader array of career choices for many middle- and upper-class Americans, whose relative economic security and wider access to information has afforded them the opportunity to choose careers borne of interest rather than economic necessity. Their increased choices are the product of the world’s increased—though unevenly distributed—wealth, itself the result of capitalism’s character as a system of considerable economic production, an attribute which even Marx himself acknowledged. With that wealth—and its corresponding increase in collective human capacity to alleviate suffering, particularly through non-governmental and intergovernmental organizations—more and more individuals are afforded the opportunity to help do exactly that, which, increasingly, many are.

They are young men and women more enthusiastic about serving the various causes of justice than the institutions of power. They are Gramsci’s “organic intellectuals”, moved by basic human empathy and the humanistic ideals of equality, liberty and justice. They understand that economic exploitation, national supremacy, political hegemony and military domination are not privileges afforded to some human beings, but curses inflicted on all humanity.

They are the doctors who would rather dwell in dilapidated hostels while helping to prevent AIDs in Africa than in luxurious hotels to serve a different clientele. They are the young lawyers who graduate from the country’s most prestigious law schools, but who would rather make pennies committing their lives to dignity for the disenfranchised than make millions writing contracts and seeking tax loopholes for major corporations. They are the many generous donors who contribute their wealth to noble charitable and political causes rather than to lavish excesses. Among them is the much-revered Palestinian leader, Edward Said, who eschewed the tranquil career of accomplished academic in favor of the often dangerous role of spokesman for his people. These men and women, who prefer the undeserved discomforts of seeking justice to the injustices of seeking undeserved comfort, are the true shepherds of peace in our time.

Theirs was the spirit found in the words and actions of Rachel Corrie, who, just weeks before her death, wrote from the now-devastated Palestinian city of Rafah: “I look forward to increasing numbers of middle-class privileged people like you and me becoming aware of the structures that support our privilege and beginning to support the work of those who aren’t privileged to dismantle those structures.”

In living her words, Rachel Corrie became more than a brave woman who sacrificed her life to protect an innocent Palestinian family (though that she certainly was); she became the most celebrated symbol of a new generation of human beings who refuse to eat from tainted fruits of the tree of injustice. No investigation and no law can sufficiently honor the meaning or legacy of Rachel Corrie. Rachel Corrie can only be honored when more “people like you and me” follow in her path, sacrifice of ourselves and become the justice that we so eagerly seek, and that she so graciously became.

G. S. Naggiar is President of the American Association for Palestinian Equal Rights.