The Electronic Intifada 16 March 2004

Daily agenda at Camp Rachel.

Olympia Reacts to the death of Rachel Corrie

Olympia is a gorgeous town on the Puget Sound in Washington State. It is bucolic, with ocean water, glacial mountains on both sides and a downtown full with quirky independent shops, restaurants, taverns and tattoo parlours. It is home to a small city of artists, college students, government workers and retirees. The county has more suicides than homicides and you feel safe almost anywhere anytime. It is a gentle and easy place to live, a natural refuge celebrated by Time magazine in 2000 as “the hippest town in the West.”

Percival Landing in downtown Olympia, Washington, this boardwalk was across from Camp Rachel and this is the view looking north at the Olympic Mountains. Percival Landing is a point of congregation for many vigils and protests as it is very visible to large amounts of traffic. A vigil was held here the first night of Rachel Corrie’s death.

It is not Rafah. Living here, under the tall evergreens with the smell of salt in the air, it is hard to conceive of life in Rafah, a Palestinian city in the Gaza Strip, which is under Israeli military occupation. Before March 16th 2003, distant Rafah was not in the thoughts of many Olympians.

The murder of a young woman from Olympia changed all of that. March 16th brought to fruition a harsh awareness of the daily acts of violence that the Israeli military perpetrates in the Occupied Palestinian Territories [OPT]. Olympia now had a face, a crumpled body, a direct line to the life experience of the Palestinians. Olympia felt bonds of solidarity with the people of Rafah that had never been there before. Education in Middle East politics gained immediacy, as did the news reports of escalating atrocities.

These were some of the consequences of the death of Rachel Corrie under the blade of an Israeli Defence Forces [IDF] armoured bulldozer. The Olympia traditions that birthed Rachel Corrie’s passionate activism came together in grief and shock, disbelief and outrage. Her death was painful for the town to bear and this communal mourning was shared by the wide circle of those who personally knew Rachel and by those who only knew her name posthumously. In the year to come, a synergism formed between the already strong anti-war movement and local Palestinian activists and this partnership enabled a robust response to both conflicts.

Media coverage of Rachel Corrie

Mainstream news of Rachel’s status was hard to come by, brief mentions drowned by the endless preoccupation with the upcoming invasion of Iraq. E-mails with updates from her associates in the International Solidarity Movement [ISM] and links to foreign and alternative/independent news sources quickly circulated within the community. These sources were rich with information that gave a more complete and complex account of what happened to Rachel in Rafah.

It was here Olympians could see candid photos of Rachel’s death, which were not presented by the United States media. The photos were the kind of combat images that burn in your brain - her body buried under a foot of dirt and rocks, her fellow activists digging her out by hand, taking care not to injure her further. Then a closer photo of the dirt and blood on her face and broken body. A photo at the emergency room in the al Najjar hospital, the trauma she suffered all too evident, she died within 35 minutes of being struck. Haunting images compounded by the fact that this was not a stranger.

These pictures, along with eyewitness testimony, directly contradicted the official declarations of the Israeli and United States government that this was a “regrettable accident.” Major media reports did not actively question this assertion, delivering it as undisputed fact. The local newspaper, the Olympian, gave the event front page coverage in its aftermath and has periodically given updates for newsworthy events.

The deep division between pro-war and anti-war factions was also evident in the public’s reaction to Ms. Corrie’s death. Reader letters in the Olympian slightly favored those critical of Corrie, they bashed Corrie for “siding with the terrorists,” citing the oft repeated image of her engaged in burning a flag, on February 15, 2003, the International Day of Protest against the Iraqi war. Readers blamed Rachel for causing her own death, rationalizing the actions of the IDF. Others defended her actions as a peacemaker and cited the real reasons for her presence in Rafah.

Olympia convenes a peace camp to protest the invasion

The first vigil mourning Ms. Corrie was the night of her death at Percival Landing on the Olympia waterfront. It had been a planned protest against the Iraqi invasion but became a candlelit forum for the news of Rachel’s death to spread. There were shrines with flowers and photos and the next day saw the boardwalk covered in pools of melted wax. But the most visible remembrance of Rachel’s death was yet to come.

In the days immediately following Rachel’s death the United States was in the final preparation for military action against Iraq. Locally, opposition to the Bush administration and the use of force in Iraq was not to be “misunderestimated.” The F15 and M14 international calls to action drew significant crowds of Olympians who marched and listened to anti-war speakers, including veterans. The now historic State of the Union address, on January 28, 2003, drew hundreds of vocal protesters to Sylvester Park to boo, jeer and laugh in response to Bush’s speech.

In Olympia, advance preparations had been made to ensure a strong and continued progressive response once the U.S. started launching missiles toward Iraq. This intense and moral commitment to peace and resistance was evident as activists converged on the Washington State Capitol grounds within hours of reports of bombs falling on the evening of March 19th.

Camp Rachel sited at Heritage Park in downtown Olympia, Washington. The Washington State Capitol Building is in the distance with its large reflecting lake directly behind the camp, it can be seen on the right of the photo.

Tents, large and small, were erected throughout the night and by midnight there was a large “base camp” and at least two dozen smaller 1-4 person tents scattered in the general area. Under a large tarp wooden platforms were laid on the muddy ground for those equipped only with sleeping bags. Food, beverages and other provisions poured in.

Despite the gravity of the situation, the mood was proactive and exciting, almost festive, and definitely full with camaraderie. On the night Gulf War II began, Camp Rachel began its occupation.

Life at the Peace Camp

Camp Rachel was to last a continuous total of 37 days in two locations and then for two days later at a third location before it’s dissolution on April 26th. It confronted thousands of local citizens, government workers and tourists with its highly visible presence in the midst of downtown Olympia. It was a 24 hour convergence point and open forum for activists to meet, discuss, educate, decompress and ultimately form bonds which long outlasted the physical presence of the action.

The Olympia camp spent the bulk of its time occupying a plot at Heritage Park, which is between the shores of Capitol Lake and Budd Inlet in the Puget Sound. The Capitol building with its large reflecting lake dominates the view to the south, to the north are docks moored with pleasure craft. The Olympic Mountains are in the background and when the sky is clear Mount Rainier towers over the Cascades on the eastern landscape. The location of Camp Rachel is literally the scene of a thousand postcards.

Conditions in the camp, while not picture perfect, were by no means as harsh as conditions faced in any warzone or refugee camp. No tanks or guns confronted the occupants. No one was arrested for assembling at Camp Rachel, nor was the camp raided at any time, as often happened in Portland, OR. There were, however, numerous challenges the activists faced to keep the camp intact and functional. There were frequent negotiations with the state administration over the use of the space, with that, the constant threat that the camp would have to disband. In the initial nights of the war, the camp was set up within 1/4 mile of the Capitol building and 1/2 mile from the Governor’s Mansion. This proximity to government buildings caused additional security precautions because of fears of terrorist activity due to the “high orange” security alert caused by the invasion.

The administration did not fear the peace activists but were concerned that other organizations would use the camp as an opportunity to stage a terrorist attack. A particular worry was the ease with which weapons could be concealed in closed tents. According to Bill Moore from the Washington State General Administration there were also rumours of anarchist groups from Eugene, OR showing up and causing mayhem. On the whole, the government seemed to understand the nonviolent nature of Camp Rachel and were willing to work with them to allow them a presence, though were not willing to concede on other issues.

The camp maintained its continuous nature by volunteers who eventually signed up for 3 hour shifts on a large calendar. When the camp first moved to its Heritage Park location, regulations about overnight camping prohibited volunteers from sleeping, eventually the rules became more relaxed and a small number of tents were set up behind the base camp.

Back of Camp Rachel at Heritage Park, after sleeping was again allowed. The blue canopy to the far right was the food preparation area at the camp.

The weather was a constant hardship — unfriendly rain chilled volunteers and turned the ground mucky. It was a challenge to keep every thing dry — provisions, literature, feet, clothes. As the camp evolved it became more comfortable and sophisticated - sofas and a portable toilet were brought in, daily agendas were posted along with a large display rack for printed materials. There was a donated cell phone, which enabled the camp to have a dedicated phone number.

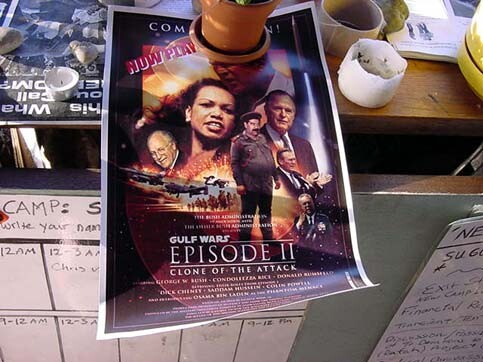

Donated poster at Camp Rachel, underneath is the sign up sheet for 3 hour shifts for volunteers to manage the camp. On the bottom right is the list of topics for the next camp meeting.

Community Reaction to Camp Rachel

In a town known for it’s tolerance, the reaction of the community that opposed the existence of Camp Rachel and rejected the messages it represented was troubling. Common was harassment from passing vehicles — often obscene, largely verbal but often punctuated with rude hand gestures. Words, not bullets or RPG’s, but words that stung coming from fellow Americans who purported to support freedom.

Other negative reactions from the public ran from fear of the protesters themselves to distaste for the ramshackle appearance of the tent compound. Others were upset that the camp was on public land and that public funds might be supporting it, or that funds might be diverted from more pressing homeland security needs. One man complained to Bill Moore that he was afraid to walk his dog along the lake, feeling physically threatened by the activists.

Mr. Moore stated that several downtown businesses felt the camp looked like a “shantytown” and would repel customers from the business district. The camp was a collection of makeshift structures, while not aesthetically pleasing in the long view, given a closer look it was apparent that housekeeping was a priority for the camp. Obvious care and respect was given to run the camp in an orderly and environmentally sound manner.

To be fair, it must be noted that Camp Rachel was sited adjacent to the construction zone for a new bridge, Olympia’s largest public works project in at least a decade. This is an area that has been torn up for over three years since a major earthquake struck in 2000 rendering the old bridge unusable. It must also be noted, that among downtown businesses, there were a large percentage that posted “No Iraqi War” signs or other pro peace statements and who gave material and moral support to the protesters.

An emotional refuge

One of the most immediate functions of the peace camp was purely emotional, especially for those who personally knew Corrie. It was a venue where protesters did not have to be alone, where freedom of speech was encouraged rather than suppressed. Many of these Americans were viscerally affected by the war — it literally made them emotionally and physically ill, and the peace camp was a healthy place to vent and find solace.

There was a great deal of anger and fear of whether the Iraqi attacks would provoke a retaliatory attack on the United States. There was disbelief at the arrogance of the administration and the complicity of the media. There was shock at the transparency of the government’s arguments especially regarding the weapons of mass destruction mantra, the length of the occupation and the secrecy surrounding projected real costs to the taxpayers.

The activists felt a deep and genuine concern for the personal well being of all of the Americans and the Iraqis, the Palestinians and the Israelis. To sincerely think and care about those in these war zones it to carry a heavy emotional burden. Many felt shame for their country’s actions in this unprovoked attack. There was much concern regarding the erosion of civil liberties under John Ashcroft and the realization that they themselves could be unfairly targeted for expressing their political views.

Because of the strident wave of patriotism, discussing concerns like these could easily get you in social trouble. At Camp Rachel, these feelings could be shared, listened to, affirmed and appreciated with out being marginalized, demonized or derided. This freedom and support cannot be underestimated as a value to the people who Camp Rachel touched.

Camp goals and activities

The mission of Camp Rachel was best stated by the words written on the back of the main sign - “HERE FOR GOOD.” The statement alluded to the fact that the organizers stated action was to keep the camp erected for the duration of the war. The second meaning, however, best described the attitude and motivation of those involved with the camp - that they are here for good, a monument for peace and justice as opposed to the rampant symbolism of aggressive and unilateral destruction.

A central function of the camp was to engage and educate the public about the truth and lies surrounding the Gulf War and Mideast conflicts. The camp was a distribution point for the dissemination of progressive news and analysis, words as weapons for waging peace. This valuable outreach was most often carried out on a person-to-person basis as people engaged in dialogues about their perspectives on the events. Most camp volunteers proved to be politically and media literate and were able to discuss issues in a friendly, intelligent and educated manner, able to cite sources as verbal footnotes.

Activities at Camp Rachel included petitions and letter writing campaigns at times to save the camp or to lobby for a more thorough State Department investigation into Ms. Corrie’s murder. There were regularly scheduled talks on a variety of issues pertaining to the war and the movement’s part in it. The broadcast of Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now became a regularly scheduled morning event. On the lighter side, there was Yoga for Peace, musical entertainment and puppet/sign-making workshops.

The camp was a starting point and an end point for actions and marches that continued in Olympia for the duration of “active combat.” Notable was the “day after” march on March 20th when hundreds of protesters took their time snaking through the downtown business district. It was an electrifying scene with the beating of drums, angry chanting and an eclectic array of signage. The procession was led by a life size wooden coffin bearing an image of Corrie and the flags of the United States, Iraq, Israel and Palestine.

Support for the troops

One delicate situation that confronted the diversity of the population at Camp Rachel was the question of troop support. As expected, this was a looming issue with the general pro-war population who seriously questioned the message sent to the troops by continuing to protest once the conflict was actually underway. In the United States, the knee jerk mentality to “support our troops” was hard to resist. Even the most ardent protester was heard to state their support for the men and women in uniform.

Large banners were erected at the camp “We Support the Troops - Bring Them Home Alive” and “Bring the Troops Home.” Again, there was a genuine concern for the people themselves, the safety and well being of both the troops and their families mattered greatly to the activists. Many held the opinion that the best troop support was to not go to war, keeping them out of harm’s way.

Some people, however, felt that, in good conscience, they could not support our troops in this illegal war. Others found their support dwindle once they discovered the war crimes being committed in their name. Reports of brutality and disrespect for the Iraqi populace and their culture did not reconcile with their vision of the troops as benevolent liberators and protectors.

It was hard not to be moved when viewing photographs of devastated and decimated Iraqis, their children and their neighborhoods. It was deeply troubling to witness this carnage and know that your country was responsible for this. It was sickening to read accounts of soldiers discussing killing and their racism against Arabs. Just as appalling to some was the mass media’s glorification of the “coalition” forces and the near joy as they met each “objective” including the staged destruction of the statue of Saddam Hussein.

Also a consideration was the humanitarian/environmental catastrophes caused by the devastation and disruption of the infrastructure, the misuse of cluster bomblets in populated areas and the free and rampant use of depleted uranium munitions. Activists knew this was not the “humane” war the Defense Department claimed it to be.

Questioning the troops about subjects such as these seemed almost unspeakable in the fervent patriotic climate that enveloped the war. Sentiments such as these could definitely raise suspicions that perhaps the speaker was not so American, maybe not one of the “ones who are with us.” It was not something you would want to bring up at work, in mixed company or to strangers.

Dissolution of the camp

Despite intense lobbying for it’s renewal, the Camp Rachel’s permit at Heritage Park ended at noon on April 24th. Reasons for enforcing the end of the permit had to do with previously planned maintenance/construction on that portion of Heritage Park. Mr. Bill Moore also stated that the area was also reserved for other events and that they had to prepare the grounds for that.

The weekend after Camp Rachel was to disband was the annual Olympia Artswalk festival and Procession of the Species, two events that draw huge crowds to downtown to view art, eat, drink, dress up like animals and have a great time. If Peace Camp could stay there would be hundreds of passer by to engage and educate about the local progressive movement. It was hard for some activists to not have the perception that the government did not want the camp intruding on this very public event.

There were intense discussions among the participants as to what its options were and what stance it should take once it’s legal occupation of the park expired. Engaging in civil disobedience was a strong possibility. In the end, activists decided it would be in their best interests to remain within the law and disband peacefully. A rally was planned and the community came together to deconstruct the camp.

Long term impact of the death of Rachel Corrie

Camp Rachel was, above all, an assertion of nonviolence and resistance to the Bush regime’s policy of pre-emptive war. The people of the camp made the decision to physically stand defiant and do the work of moral witness so that the real history of the war will not be lost to the memory hole or to the administration’s intense campaign of revisionism.

Ms. Corrie’s death intensified and complicated things, lending a poignant depth not likely to be forgotten by those who participated at Camp Rachel. The community came together and bonded in a manner that will carry through to the 2004 elections when the opposition to Bush in Olympia will be fierce. There is now a more coherent base from which to draw in the event of the threat of another invasion, activists are allied and better prepared for further action. Many new people were brought into the movement, people who are outside the stereotype of the typical activist, yet aligned with the principles of nonviolent protest.

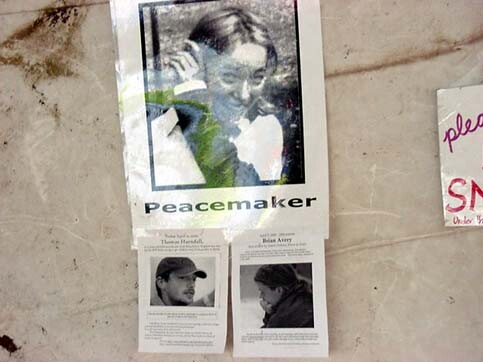

On the back wall of Camp Rachel hung these three pictures of IDF casualties. The laminated Peacemaker photo was attached to the mock wooden coffin that led the protest march on March 20th, the day after the war began.

While it is still too early to realize the full long term impact of Rachel Corrie’s death on the population of Olympia, one thing is for certain is that it bought a much greater visibility to the ISM and the politics of the Mideast conflict. There is a continued concern for the citizens of the OPT and the residents in Rafah in particular.

There are several projects in the works including the Olympia Rafah Sister City Project, which is dedicated to Rachel Corrie’s belief that “cultural exchanges between our two communities could result in significant social change.” Numerous locals have made the commitment to travel as witnesses to the conflict, many have aligned with the ISM. Reports from the front are circulated by email and in person upon the activists return. Some write further of their experiences, others are working on video projects, most are active in speaking out for the cause of the Palestinians.

Peace Camp has been sorely missed as the occupation drags on with no visible progress and an ever inflating price tag. The continued manipulation of the White House keeps Olympia’s emotions at the surface. However, there was no formal place to gather to share disgust at the Tailhook landing or laugh at the transparencies of the Bush/Cheney/Powell/Rumsfeld lies du jour. The political activities of the town are unabated, Olympia remains a sanctuary for progressives. There is hope that a full time space can be found and modeled on Camp Rachel. Until then there are the cafes and streets, living rooms and meeting spaces, classrooms and churches where Olympians will continue to meet and organize for peace and justice.

Originally from New York, candio. now lives in the Pacific Northwest. She is an artist, writer and activist. Her work has been shown in galleries and museums, in private collections internationally and on the street. She has a history of writing for alternative presses and arts publications and currently publishes online. She is also researching a book on trauma and it’s physical and psychosocial effects.

Related Links