The Electronic Intifada 8 April 2005

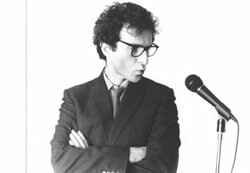

Ivor Dembina

Dembina introduces the show by explaining that it is the result of a trip to Jenin he made as a guest of the International Solidarity Movement (ISM), when he resolved to write “the joke that will end the Middle East crisis.” However, it is his experience growing up Jewish and becoming socially aware that drives the show, which has toured England, the U.S., and is currently performing in Israel and Palestine.

Having grown up as a Jew in North London, he explains that this meant that he was especially aware of three things: the Holocaust, that Jews are clever, and that Jews are funny (perhaps his most controversial claim in the revue is when he says, in contrast, that Palestinians are not funny). He reflects on the pride he felt after Israel’s victory during the 1967 war, after which it occupied the Golan Heights, Sinai peninsula, the Gaza Strip, and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. But he remembers that little voice in the back of his head that whispered, “The people we beat in the war weren’t the people who put us in the gas chambers.”

However, at his family’s dinner table one would hear that the only good Arab was a dead one (an idea that a young Dembina challenged by replying that there were plenty of bad dead Arabs). It wasn’t until he was a day-care worker, and a white toddler in his care identified a boy she was squabbling with as “the boy in the green jumper” rather than by the dark color of his skin, that he became passionate about social justice. Whether it be about socialism or saving the whales, if there was a protest to be had, he was there.

But criticism of Israel (which he calls his favorite part of America) was off-limits. However, as interrogative of society as he is of himself, Dembina explains that when he asked questions and wasn’t getting answers, he only asked more questions. It wasn’t long before he became uncomfortable with what Israel, which he had always held in his heart as a safe haven for the perpetually persecuted Jews, was doing while claiming to represent the interests of Jews worldwide.

Though himself not necessarily a believer in a god, when he found himself on a hill overlooking Jerusalem, Dembina had a spiritual experience that only solidified his concern for what eventually happens to the land. And what he saw in Jenin in 2003 confirmed his belief something very wrong was happening in the region.

While he was there, a young Palestinian from Jenin committed a suicide bombing attack in Tel Aviv, and he visited the family of the bomber. Soon the Israeli tanks rolled in, and Dembina attempted to intervene with Israeli soldiers there to destroy the family’s home, explaining that it wasn’t just the bomber’s home, it was that of a whole family. After the house was demolished, the soldier joked, “that’s not their home anymore,” to which Dembina responded, “this is not a subject for comedy.”

With the right balance of and blending of the wisdom possessed only by those who examine the ugly aspects of human nature and the wit of somebody naturally funny (maybe Dembina would insist that his brand of humor is the birthright of anybody who bears a resemblance to Woody Allen), the comedy act isn’t necessarily as knee-slappingly funny as it is memorable and at times profound (without forgetting that it is a comedy).

Indeed, when he returned to his original spot of inspiration overlooking Jerusalem, he no longer sees the city because of the towering concrete wall that has been recently erected. And it should come as no surprise that Dembina, who was once that little boy who couldn’t grasp why being Jewish and British had to be mutually exclusive, like his teacher seemed to suggest, would come to the conclusion that people are basically the same, and that together Palestinians and Israelis should build a brand new country (he suggests the name Israelstine - the only country to be named after his accountant).

Though this reviewer is not sure how much, if at all, Dembina alters his monologue to suit his different audiences (be they English, American, Israeli, or Palestinian), it seems as though Dembina especially tailors his act to other Jews — though without the effect of excluding other audiences. It is critical that Dembina structures his act the way that he does, by provoking his (primarily Jewish) audiences’ imagination by illustrating the potentially dire situation of being a Jew in an under-curfew Jenin, and then gaining his audiences’ trust by discussing his personal experiences while growing up, before fully tackling the current situation in Israel-Palestine.

Stand-up comedy is the most difficult type of comedy, as the lone performer is totally vulnerable to the audience. And this is why it is almost always very good or very bad. It is a testament to his talent that Dembina can successfuly wrestle such a weighty and divisive topic as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a monologue comedy. But what a fortunate thing — to be able to make an audience that lives out the conflict laugh, and educate other audiences with the same material.

Related links:

Maureen Clare Murphy, currently living in occupied Palestine, is Arts, Music and Culture Editor for the Electronic Intifada