Israeli Army jeeps take position around the Old City of Nablus.

6 March 2007

I don’t know where to begin. It would make sense to start at the beginning, but the beginning was ages ago, long before I arrived. Nor is there any end in sight. I was plopped into life in Nablus for one short week and I’m not sure if I’ll ever recover. And as I write from a place of safety, the people of Nablus continue to struggle, not just with the nightly incursions, bombings, and assassinations, but also simply to remember their own humanity in spite of the most inhumane treatment. I’m trying to rediscover my own, to revive the parts of me now polluted with anger, or worse — shut off, as if a part of me is dead. And I was there for just one week.

We arrived on Sunday to help volunteers from the UPMRC (Union of Palestinian Medical Relief Committees) deliver food and medical services. Dozens of jeeps and hundreds of soldiers had surrounded the Old City and declared curfew on all of Nablus. Their stated mission was to capture or assassinate eight fighters from Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, the armed wing of the Fatah movement. Meanwhile, the 40,000 residents of Nablus Old City were trapped in their homes, inside a war zone, unable to go to work or school, or even to buy food for their families.

In the Old City of Nablus the ususally congested streets are empty during curfew.

According to many families, this invasion posed a greater threat than those of the past because it was coming on top of an already desperate economic situation caused by the US-led embargo after the Hamas elections. Whereas in the past residents would stock up on food and supplies in case of an invasion, these days people hardly have enough to meet their current needs. People are working to buy bread for that very day, so the invasion was not only leaving them out of food, but preventing them from going out to make the money they needed to buy more.

Residents of the Old City call out of their windows that they need food and medicine.

Sometimes the soldiers allowed the doctor and medical volunteers through. Often they didn’t. As night fell and soldiers refused our passage to the hospital, we decided to call it a day and hoped we’d have more luck in the morning. As we were making our last bread delivery, eight soldiers walked by our group with one Palestinian. The man spoke quietly as he passed us, and the medical volunteers immediately relayed to us the message he had given them: “I am being used as a human shield.”

Israeli soldiers detain medical relief volunteers and prevent them from delivering medical services.

Using civilians as human shields is a serious violation of international law, and we immediately called B’tselem (the Israeli Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories) and Machsom Watch (Israeli women who monitor checkpoints but also have a good knowledge of Israeli law) to file reports and hopefully help free the man. One Israeli contact explained that the practice is so common that we probably couldn’t stop it before the man would be replaced with another, and another after that. We wanted to check with the man’s family to see if there was anything else we could do, but the army had blocked off their whole neighborhood.

It was with an intense feeling of helplessness that we checked into the Crystal Hotel that night, bombs exploding in the Old City nearby under a heavy rainstorm. We slept soundly and were woken at 6am by the jeeps again declaring curfew over loudspeakers through the streets. We met the medical workers and began making rounds again. Many families needed bread. One child had a broken arm and needed treatment. Occasionally while we were visiting families, soldiers would barge in with dogs, herd everyone into one room, and search the rest of the house. I would try to amuse the children to distract them, or maybe to distract myself. I tried to imagine what it would be like to have my home raided, my possessions destroyed and made a prisoner in my own home. Most raids ended quickly but some homes were occupied for days on end. We couldn’t get to those dozens of families, but heard stories from neighbors and medical workers.

A Palestinian man is handcuffed, blindfolded and detained.

The Awad family was also confined to one room of their home while soldiers took over the rest of the house. One floor was reportedly transformed into an intelligence center, another into a prison, and the basement into a makeshift interrogation center. We had already begun to hear stories from young men returning from interrogation — affectionately referred to as “Hell” in Arabic — while others went missing. In alleys we would find men handcuffed and blindfolded, being led into jeeps while soldiers aimed their guns in our direction as an unspoken warning against speaking or photographing. I kept my camera hidden, knowing that one Reuters cameraman had already had his film taken at gunpoint.

UPMRC volunteers were also starting to disappear, including one man we’d delivered bread with a few hours before, named Alaa. I’d last seen him while I was carrying one of two sick children from the clinic back to their home, since their parents could not come get them. After we’d delivered the kids and were walking away, we heard shooting from close behind us, just beyond the children’s house. Within minutes, we learned that an unarmed man had been shot dead on his roof, and his unarmed 20-year-old son Ashraf’s elbow had been blown off by a dumdum bullet. Soldiers entered the house and detained young Ashraf, who was in shock. When Dr. Ghassan (from UPMRC) and Alaa (a volunteer) attempted to enter the home to bring the father’s body down to an ambulance, soldiers detained them both. They held the doctor for several hours and then let him go. They kept Alaa in custody, saying he “looked suspicious.”

Alaa and Ashraf were eventually released and we took their reports the next day. Ashraf was in the hospital, surrounded by friends and family. The mood was somber, but he agreed to tell us his story:

On Monday around noon, my dad went up to the roof to check on the water, which was not working. I sensed some movement outside and through the window I saw soldiers. I ran upstairs to warn my dad that the army was near, and as I spoke the words a dumdum bullet hit my right elbow, shattering it. My dad ran towards me to save me. When he looked back towards where the bullet had come from, he was shot by a sniper in the neck, and then in the head.I called for help and tried to give my dad CPR. When the ambulance arrived, it was surrounded by jeeps on all sides and prevented from reaching our home. The soldiers took me into one of their jeeps while my father was still bleeding seriously. They held me for an hour and a half before taking me to an ambulance. One soldier bragged that he was the one who shot me and my dad, and followed me to the ambulance in a jeep by himself. My family told me afterwards that after the soldiers made sure of my dad’s death, they allowed the medical workers to carry him down.

Ashraf Tibi in his hospital bed.

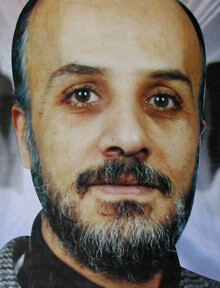

Anan Tibi

Ashraf pointed to a smiling picture of his father that hung on the wall opposite his hospital bed. I asked our translator how Ashraf knew CPR, and he explained that Ashraf volunteers as an Emergency Medical Volunteer, and is the type of person who risks his own life to save others. We asked Ashraf if he had a message to the American people. His response: “We are not terrorists — the soldiers will not find what they’re looking for here. We are civilians, and we want to be left alone so that we may live.”

There was a great deal of misinformation surrounding Ashraf’s story in the mainstream media. Some news sources claimed he and his father were armed; others said they were walking around, breaking curfew. I visited the roof, I saw the bloodstains, I spoke to the medical volunteers who evacuated them. It is so crucial to get these stories out and I’m grateful for any help from you, especially as the media seems to have moved on from the story. This is just the first of several reports by me on the Nablus invasions; Alaa’s and others’ stories are still to come.

[… NEXT]

All images by Anna Baltzer.

Anna Baltzer is a volunteer with the International Women’s Peace Service in the West Bank and author of the book, Witness in Palestine: Journal of a Jewish American Woman in the Occupied Territories. For information about her writing, photography, DVD, and speaking tours, visit her website at www.AnnaInTheMiddleEast.com

Related Links