The Electronic Intifada 10 March 2021

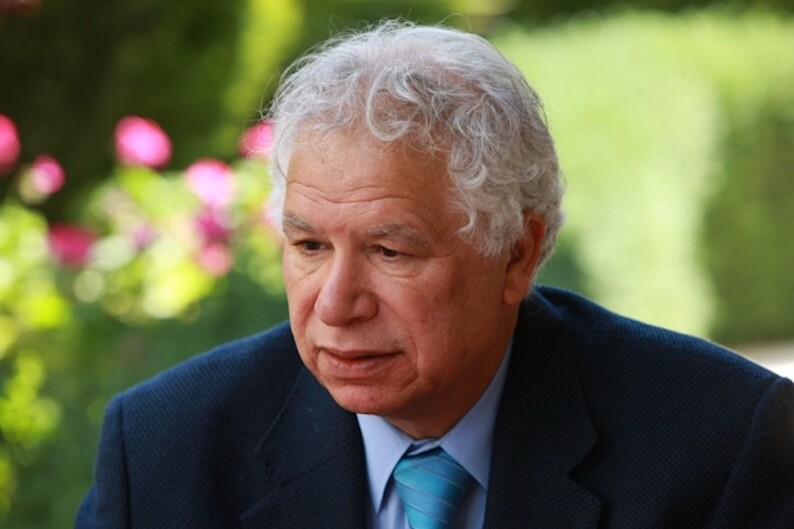

Mourid Barghouti (Dia Saleh)

The memory of how I met Mourid Barghouti rushed back to me recently when I heard that he had died.

It was 2006. Barghouti was sitting a few seats away from me at a conference on Palestinian literature at the University of Manchester.

I didn’t recognize him at first.

He seemed like an ordinary guy. He looked quite Western to me then, though he would probably not have been happy to be described as Western-looking.

He could have been a supporter of the Palestinian cause, a journalist, or more likely an academic at the university.

When I got up to present a paper – part of my PhD research – on Palestinian literature of resistance, it was clear that the topic interested him. He started writing things in his small notebook.

He smiled when I returned to my seat and said “well done.”

Then the chair of the conference introduced Barghouti. The introduction was long.

Barghouti didn’t even make eye contact with the chair until the last moment – when he was given the floor.

Barghouti then stood up calmly and walked to the stage to talk about Palestinian writing in exile.

He read parts of his book I Saw Ramallah. Translated into several languages, it brought him critical acclaim and various international awards.

Immediately after Barghouti had finished his presentation, somebody in the audience started heckling him.

It was a rude interruption, not the sort of interjection that normally occurs during conferences with established academics and writers.

Yet Barghouti did not appear in any way shocked. He picked up his papers and book and looked up slowly, removing his reading glasses.

The heckler was trying to make the point that Palestinians should accept their situation and not reminisce about an idealized homeland that never existed. It was the Palestinians’ fault for leaving their homes in the first place, the heckler said.

Barghouti remained calm and let the man finish.

When the heckler finally stopped, Barghouti responded with some succinct questions.

He asked what would happen if Palestinians simply accepted the situation they were in.

Why should Palestinians give their oppressors the legitimacy they are seeking? And why are Israel and its allies so obsessed that Palestinians just accept everything?

Barghouti did not wait to see if the heckler had more to say. He returned to his seat as the audience applauded.

“Hidden silent spot”

We had lunch afterwards.

Barghouti asked about my experience of leaving Gaza and coming to the UK to do a PhD in English.

I wanted to quote him his own words from I Saw Ramallah:

“The stranger is the person who renews his residence permit … He is the one whose relationship with places is distorted, he gets attached to them and repulsed by them at the same time. He is the one who cannot tell his story in a continuous narrative and lives hours in every single moment … He lives essentially in that hidden silent spot with himself.”

Instead, I told him that I wanted to be a writer just like him, that one day I would write about Gaza the same way he wrote about Ramallah.

Unlike Barghouti, I have never written a memoir or a book of poetry in Arabic.

Like him, I am an exiled writer. And I share with him an aversion to being pigeonholed by being labeled an “exiled writer.”

I haven’t suffered as much as he suffered. I was never deported from Cairo in handcuffs after opposing “normalization” with Israel.

I never moved to Beirut during a civil war like Barghouti did, only to be ostracized because of his critical views and then leave for Budapest.

I have never been a nomad searching for a home.

I reread his 12 books of poetry in Arabic and quoted some of them in my own work.

His poem “You and Me” begins:

You are as beautiful as a liberated homeland

And I am as tired as an occupied one

You are sad like a betrayed person who continues to resist

And I am anguished like a war about to happen.

The third line of that poem struck me most.

It felt like he was writing about my beloved Gaza.

A strip of land on the Mediterranean that is beautiful yet besieged.

A place that has been battered by Israeli force yet continues to resist despite the betrayal of everyone around it.

Refuge in names

When Barghouti wrote about a particular place, he captured its essence.

He was searching for home and identity within a complex matrix of exile, memory and disdain for the political reality confronting him.

Landmarks and the names of places around him became very important as he searched. They gave him refuge.

Born in 1944, Barghouti left his village of Deir Ghassana in the West Bank during the 1960s. He went in search of a university degree from Cairo and hoped that he could go back and be with his people.

But – with the West Bank under Israel’s military occupation since June 1967 – he never was able to go home.

His home became his words and the places he passed by.

In his poem “Radwa,” Barghouti wrote:

When I left

Knocking on the door had a different meaning

My home address changed.

Those beautiful and simple words resonate so deeply with anyone who has experienced exile or needs to address questions of identity.

I remember reading those lines a few years after I had arrived in London and feeling nostalgia hitting me hard like a punch in the gut.

I no longer knocked on anyone’s door.

I was exiled. I had no family to visit and no unannounced visitors who wanted to come and drink Arabic coffee with me.

I sat alone in a flat and read lots of books while watching Gaza being bombarded on the news.

Thirty years after his exile began, Barghouti went back to Ramallah for the first time in 1996.

It was the era of the Oslo accords between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. Numerous commentators were talking about peace in the Middle East yet Barghouti was under no illusions.

In I Saw Ramallah, he writes: “The others are still masters of the place. They give you a permit. They check your papers. They start files on you. They make you wait.”

It was his plain words that made Barghouti one of the giants of Palestinian literature.

He resorted to metaphor much less than Mahmoud Darwish, Ghassan Kanafani, Emile Habibi, Sahar Khalifeh and so many other brilliant Palestinian writers.

He didn’t even try to paint a picture with his words. He instead created a tapestry of feeling that all Palestinians have experienced.

A mosaic of pain, irony and cynicism. A mosaic of real life.

I have tried to follow Barghouti’s lead with my own writing. But the English language always fails me.

Expressions like “knocking on the door” and “drinking coffee” do not have the same weight in English as in Arabic.

Perhaps it is too late for me to write in Arabic. But it is never too late for me to describe places in Palestine like Barghouti did.

It is never too late to examine how these connections create an existential dilemma for Palestinian writers.

Our homeland has shaped us. No matter where we travel and no matter what we imagine, we are always connected to Palestine and the struggle for its liberation.

Excerpts from “You and Me” and “Radwa” are translated by Ahmed Masoud.

Ahmed Masoud is a writer, director and academic based in the UK.