The Electronic Intifada 15 February 2011

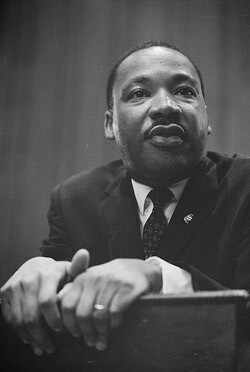

Martin Luther King, Jr (Marion S. Trikosko)

Martin Luther King, Jr wrote in his much-lauded 1963 Letter from Birmingham jail that the greatest obstacle to a movement for equality was not the extremist but the white moderate:

“I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice …” King criticized the moderates’ opposition to direct action and their advice to wait until the environment became more suitable.

Today, the American arena of this human rights struggle has arguably shifted from Birmingham to Arizona, but the greatest worldwide arena is undoubtedly Cairo. And still, the greatest stumbling block is the “moderates.” Let me be blunt: any state or individual that does not support vastly nonviolent uprisings in the Middle East is guilty of this commitment to peace divorced from justice, which is inherently a false peace. Obama’s tepid call for reform situates him with the moderates who King decries, telling the oppressed people to wait rather than supporting their direct action. Clinton’s call for restraint on both sides, when the violence and might of the two groups are so vastly asymmetric, shows the preference for order over justice that King laments.

Perhaps the most explicit formulation of this commitment to “peace” that hampers and even counteracts equality and justice comes from UK Foreign Secretary William Hague, who said in a recent interview with The Times: “Amidst the opportunity for countries like Tunisia and Egypt, there is a legitimate fear that the Middle East peace process will lose further momentum and be put to one side, and will be a casualty of uncertainty in the region.”

This sentiment sadly pervades the Palestinian-Israeli “peace process,” in which direct action like the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement is decried by “moderates” as causing tension and being antagonistic and unproductive. What is the value of peace — and can such a thing really be called peace — if justice is not attendant? Such a thing is not peace at all; it is merely order, and order can be sustained in the most terrible of dictatorships. In fact, it is arguably better sustained in dictatorships than open democracies.

Taking this a step further, these “moderate” stances expose bad faith on the part of those who do not stand with the revolutionaries, showing not only a commitment to false peace but a denial of the values they claim to hold dear. Tony Blair’s failure to support this homegrown movement against a dictator is astounding given his support for the invasion of another country — Iraq — supposedly to oust a dictator. The Western power is thus sanctioned to invade and to change regimes, but the people actually under that regime are not sanctioned to do so. Blair’s paternalistic attitude feels akin to Bernard Lewis’s dismissive formulation of “Islamic Concepts of Revolutions” (1971), in which he insultingly compares thawra (the Arabic word for revolution) to a camel rising off the ground and links it to excitability but not to a struggle over principles, rights or values.

Israel’s stance also exposes bad faith, for it has stood by its ally Mubarak and thus in opposition to a popular movement for democracy, when it proudly (if unjustifiably) calls itself the only democracy in the Middle East. Amos Gilad, the Israeli Director of the Political-Military Bureau of the Ministry of Defense, stated at this year’s Herzliya conference that “if we allow — or if there is democracy process in the Middle East — it will bring for sure — or let’s say, quite sure — dictatorships that will make this area like hell.” He praises Jordan’s “stability” but says that “if there is free elections, I don’t know who will emerge.” The implication is twofold: firstly that stability and order are more important that a people’s self-determination or justice, and secondly that Israel can handle democracy but other countries in the Middle East — Arab countries — cannot responsibly handle democracy. It is infantilizing to suggest that a people cannot responsibly, or do not have the right to, choose their leaders, and this anti-free-election stance is again ironic given Israel’s pride in being a “democracy.”

Most damningly, the lack of immediate American support flew in the face of the “American” ideals of equality, democracy and freedom. It is with deepest irony that the US failed to stand with this nonviolent movement for democracy when American textbooks teach young citizens to celebrate and morally sanction a violent revolution for democracy: the revolution for America itself!

There is a racist and essentialist conception in some warmongering propaganda that “they” (Arab or Muslim) cannot understand, or even hate, “our” (American, Israeli, or Western) values such as democracy. This includes Bush’s claim that people of another culture “hate our freedoms,” and pro-Israel ads such as the following poster found in New York subways in 2005:

“They [an unspecified group indicated only by the picture of a young Arab boy] target Israel, because Israel shares America’s values — democracy, freedom of religion, women’s rights, a free press …”

The vulgarity of this dichotomizing of peoples along the lines of cultural values has been blatantly exposed by the Egyptian revolution, an organic uprising of a people — largely Arab and Muslim but encompassing many religious and socioeconomic groups — for democracy. Given the Egyptian populace’s fervor and personal sacrifices for freedom, and the lack of support from “moderate” Western regimes, it should be clear that democracy and freedom are not values owned by America, Israel, or “The West.” These values are universal. And today, as thousands have gathered in Cairo in their name, they are more rightly called called Egyptian — rather than Western — values.

Paula Rosine Long is a poet and activist from North Carolina. She is currently a graduate student at Cambridge University in Middle Eastern Studies and is writing her thesis on Edward Said’s role in Palestinian collective memory.

Related Links