The Electronic Intifada 21 September 2004

Samia A. Halaby

Samia Halaby was twelve-years-old when Israeli soldiers arrived in Jerusalem. Born in the midst of Palestine’s bloodiest uprising against British occupation, Halaby was no stranger to colonial oppression, but something was different this time. She sensed it in the indescribable arrogance a British soldier used when he searched her school bag: His expressions, his motions, were the presage of a storm.

In the coming years, Halaby became a child of the infamous Nakbe, “the tragedy” that drove over 800,000 Palestinians from their homes, and massacred some uncountable thousands for the founding of Israel’s exclusive state. It was not until Halaby’s family arrived safely in Beirut that she and her sisters picked up pencils and began to draw.

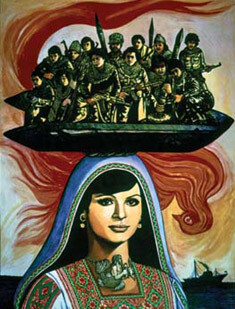

Samia A. Halaby, Al Quds, 2003. Acrylic on canvas, 213 x 123 cm.

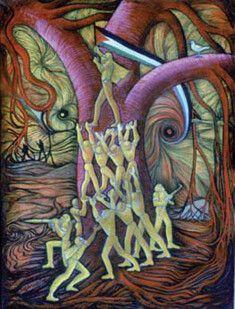

Samia A. Halaby. Acrylic on canvas.

Sketches became paintings, paintings sculpture and sculpture turned into suspensions. Today, to walk into Halaby’s studio loft in Tribeca, Manhattan, is to walk into the forensic laboratory of a 56-year investigation. Abstract, paper-machete mobiles dangle from the ceiling like sleeping memories; dog-eared history books litter the tables. It is Halaby’s living museum, and a reliquary to artists, either dead or jailed, who represent revolutions from every continent.

As a Palestinian artist, Halaby’s work is, intrinsically, cultural resistance. Compared to many of her contemporaries, her circumstances have been rather fortunate. Following several years of exile in Beirut, her family moved to the U.S., where Halaby studied Cubism, Soviet Constructivism, American Abstract Expressionism and the Mexican Mural Movement. She earned a masters’ from Indiana University, then taught at the university level for 17 years. In the 1970s, Halaby moved to New York—perhaps an inevitability for any artist in the U.S.—and by 1989 she became the first artist living in North America to exhibit her work at the Havana Biennial.

Although the majority of her life has been at a safe distance from Israeli oppression—where being a Palestinian artist, or merely painting in green, black, red and white are grounds for arrest—Halaby belongs to an existential generation of artists whose consciousness was shaped by the Nakbe. Describing this generation in her recent book, Liberation Art of Palestine, Halaby stated, “They emerged from the tragedy ready to rebuild, but what they would rebuild was not known through their own experiences.”

The emotional losses that Palestinians incurred after 1948 were indeed radical. Halaby heard many accounts of the mass expulsion of Yafa (now called Jafa), when thousands of Palestinians were forced into boats and ordered to set sail for Egypt, Lebanon, anywhere. Apparently, the Palestinians did not move fast enough for the Israeli Army’s liking, so they were urged along with live ammunition. The consequences were all too predictable: Overloaded with panicked families, many boats capsized before leaving the harbor.

Elsewhere in Palestine, multiple villages were targeted for massacre by the Zionist authorities, to set an example to neighboring communities. As if genocide were not enough, many remaining villagers were subjected to death marches. “People were forced to empty their water supplies, then sent into the wilderness,” Halaby says. “Since the Israelis thwarted every attempt to chronicle the Nakbe, including a major oral history project, it is very hard to quantify how many people died.”

Al-Awda’s Musa Al-Hindi often compares Zionism to the European settlement of the Americas. “In both the Palestinian and American cases,” he recently wrote, “historical and cultural ties that existed between the native populations, on the one hand, and their lands on the other, had to be erased, obfuscated or rewritten.”

In Liberation Art of Palestine, Halaby marks the beginning of the artistic liberation movement with an exhibition of oil paintings that opened in Ghaza in 1953. Works such as Where To?, an exhibition of the work of Ismail Shammout, which depicted an old man leading children though the wilderness during the massacre of Al Lydd, received an overwhelming response. For the first time in a long five years, Palestinians were able to resolve a “pain that had simmered on a private level,” and accounted for a “bottled up hope for liberation.”

The Nakbe was just one of many focal points for Palestinian artists. Following Israel’s 1967 occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, censorship reached new heights, but so did, conversely, imagination. Finding materials both too expensive, ceramicist Mahmoud Taha began sculpting with collected pieces of Israeli bomb shells.

By 1968, as Palestinian artists found a new exile base in Amman (Jordan), the liberation theme had become almost inseparable from art exhibitions. “It was not possible to show artwork that had no connection to the movement, and anyone who didn’t was considered backward,” Halaby recalls Taha saying.

Amman’s art scene reached its pinnacle in 1969 following the victorious Battle of Al Karameh. For the first, perhaps only, time in history, a popular Palestinian military front—if one could call it that given Israel’s technologically superior odds—had thwarted an Israeli tank offensive on a captive community. To commemorate the battle, artists from the Wihdat refugee camp strung twelve tents together for an exhibition.

Abdal Rahman Al Mozayen, “The Martyr Dallal Al Mughraby,” 1987. Oil on canvas, 80 x 60 cm. (Photo: Samia A. Halaby)

Abdal Rahman Al Mozayen, “Fighters,” 1971. Oil on canvas, 70 x 50 cm. (Photo: Samia A. Halaby)

Among the notable features was Abdal Rahman Al Mozayen’s exhibit of posters that he made overnight to warn Palestinians of the impending attack. Lacking proper materials, such as type fonts, Al Mozayen composed a series of symbols to organize the community to its defenses. Their meaning was not only universal to Palestinians, but instructive, and became part of an ongoing narrative of symbolism that characterizes Palestinian art. Or, as Al Moyazen’s colleague, Mustafa Al Hallaj, explained, “[they are] the moments when ordinary objects concretize in memory and become socially useful symbols.”

Today, according to Halaby, Al Mozayen is completing a collection of drawings to document the April 2002 massacre of Jenin, in which over 50 civilians were killed.

“We must show all of our experiences honestly, and we can even show massacre to children but it mustn’t frighten them,” Al Mozayen told Halaby for her book. “It must be done in a way that informs and gives rest.”

September 1970—Black September—soon vanished the short-lived hopes of Al Karameh, as Jordanian forces collaborated with Israel and the U.S. to unleash a systematic persecution on Palestinian communities. While official tallies simply don’t exist, estimates of Palestinian deaths range, from both sides, between 5,000 and 20,000.

But Palestinian art had already taken root in the surrounding Arab cities of Damascus and Beirut, and the resulting influx of Amman’s artists only heartened the movement. Within a couple of years, Al Mozayen and Al Hallaj founded the Studio of the Revolutionary Artists of Damascus. Meanwhile, the acclaimed Jordanian sculptor Mona Saudi, and her sister Fathiye, a pediatrician, also migrated from Amman and landed in Beirut where the Union of Palestinian Artists had recently been formed.

With periodic visits en route to Palestine, Halaby also frequented Beirut’s art scene. “Hope made each radical endeavor an immediate success,” she said of Beirut, which, to the Arab World, is synonymous with Paris’ Left Bank. “Beirut became the center from whence ideas emanated.”

Beirut, as many know, was not without tragedy. As DePaul University’s Norman G. Finkelstein recently documented, Israeli forces, under Defense Minister Ariel Sharon’s orders to “root out Palestinian terror,” massacred Beirut’s defenseless refugee population. Following the 86-day campaign—which began with bombing in June 1982, and culminated in the butchery of the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in September—the official Palestinian death toll exceeded 20,000.

Throughout the shelling, Fathiye Saudi likened her sister’s desperate attempt to rescue art to a doctor performing open-heart surgery: “…as though each work of art was the heart of mankind… we had the new task of touring the destroyed neighborhoods of Beirut searching for homes still undamaged for the safekeeping of these paintings.”

This October, Halaby will visit Palestine for a few weeks with an international delegation called Artists Against Occupation. Stretched out on the floor of her studio is a work in progress: the painting of a colossal raised fist, an unmistakable symbol of revolution. She has chosen this one to stay behind, as it will never make it through U.S. Customs. Besides, she says, it will better serve Al-Awda’s upcoming exhibition, titled, “Representation and Misrepresentation,” which commemorates the 22nd anniversary of Sabra and Shatila.

Halaby scans the walls of her studio. They are a firework display of abstractionism. She hasn’t decided which of the myriad explosions will survive the trip to Beirut. It gets late and she still hasn’t decided. These matters are for tomorrow: A day closer to her story’s ending, a day nearer to return.

Zachary Wales works with the New York Chapter of Al-Awda, the Palestinian Right of Return Coalition. He moved to New York in October 2003 after working in Namibia and South Africa for four years as a media research consultant and news correspondent.