The Electronic Intifada 25 February 2013

Readers who already possess works with the words “Home,” “Exile,” “The search for peace/homeland/justice” in their titles may wonder what another collection can add on this subject of loss and thwarted hopes.

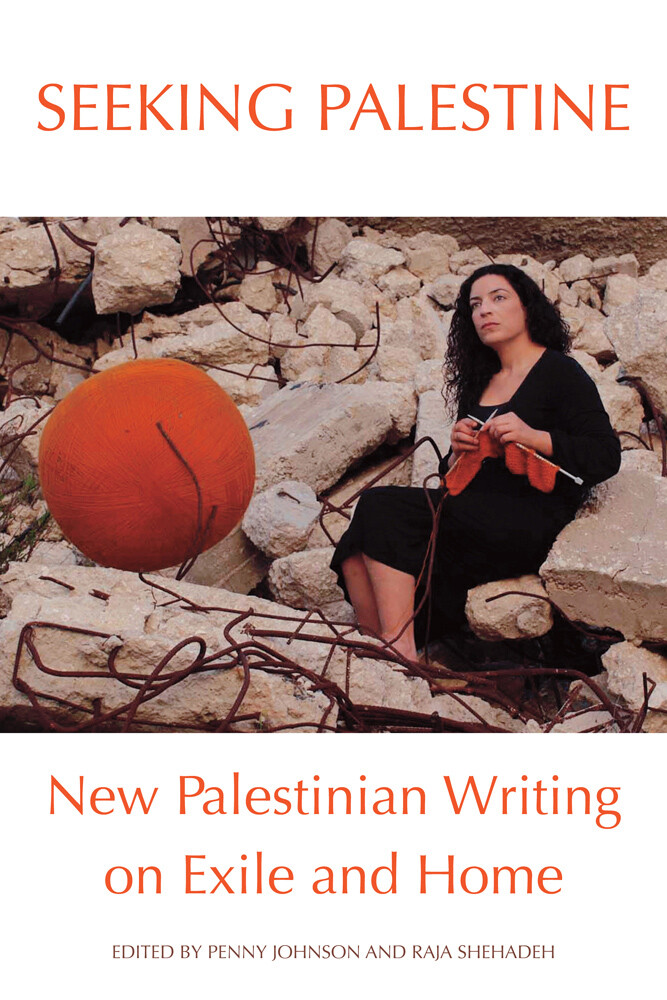

But Seeking Palestine: New Palestinian Writing on Exile and Home, edited by Penny Johnson and Raja Shehadeh, is a unique collection of writing and images by artists coming from a variety of different disciplines, from academics in the social and political sciences, to poets, award-winning fiction and nonfiction writers, the writers of bestsellers as well as visual artists. It is a motley variety of styles and approaches with an unwaveringly high quality of writing throughout, a credit to the editors as well as the contributors themselves.

This is an extraordinarily frank, fresh and unsentimental assessment of what Palestinians are and have become. It is not only a testimony as to the strength, dedication and sticking power of Palestinian people, but also of the writers themselves.

It is a book not just of ideas and bearing witness, but a catalogue of astonishing characters from the Miss Havishams of East Jerusalem (Hammami); the tuna fish can thieves of Jerusalem orphanages (Abulhawa), the poets struck dumb by the prowess of their taxi drivers (Barghouti), a book where girls throw up on long journeys from Palestine to Beirut (Said Makdisi), are turned into their stepfather’s mistress at the age of nine (Abulhawa) and batter and scream to be let in to readings in Jenin (Shibli), where architects are challenged as to why they never bore children by stonemasons and rebuked for mentioning God (Amiry), revolutionary leaders organize in elementary schools (Nabulsi), young women fight Israeli officials seeking to deport them from airports (Barakat) while other women play football, have their bags stuffed with sweets and eat Sayideyeh in Gaza to fulfill the wishes of those who are prevented from doing so themselves (Jacir).

The characters in Seeking Palestine are dying to get out of the strictures that have been imposed on them. They are also unified by anxiety (Said Makdisi), pushing against doors (the title of Lila Abu-Lughod’s piece) screaming at doorkeepers (Shibli) and railing against categorization (“My personality is too big to fit that box!” Amiry seems to say in different ways in her piece “An Obsession.”) We will not just be pawns in anyone’s political game, seems to be the common message conveyed by these characters and anyway, at the end of the day, as the men in Mourid Barghouti’s taxi point out, the joke is on them, they’ll never succeed, we are not going anywhere, as one passenger states: “Their project isn’t going well … An Israeli state at our expense isn’t working out for them. How do they think they are going to get away from us?”

The shrine of Darwish

Time is a player in this book. It sharpens up memory (Abu-Lughod, Said Makdisi, Elmusa) and stands still on wristwatches in protest at Israeli airport searches (Shibli). The chronological order of events is played around with (Abulhawa, Shehadeh, Amiry) with the button being held on pause for the final hanging image in Barghouti’s heart-in-the-mouth extract “The Driver Mahmoud.”

Barghouti, the poet, here writes in prose, but poetry is present in the form of emerging writer and poet Fady Joudah, a Palestinian-American physician whose work is published alongside other more established poets like Sharif Elmusa. The shrine of Mahmoud Darwish is touched by many of the writers in this collection and quoted, sometimes at length, by many. Two of Darwish’s translators to English (Joudah, Hammami) contribute to this collection. His presence is felt throughout the book, underscoring the importance not just of Darwish’s work, but of the critical role that writing, poetry and the creation of images that resonate is in forming a collective spirit and consciousness.

Compared to some earlier collections of Palestinian prose, narrative nonfiction and poetry, particular skill is found in this collection. All of the authors surmount the specific challenge posed to all Palestinian writers to be able to speak outwardly and inwardly at the same time — to be able to address and explain to those who are unaware of the situation while also engaging, entertaining and possibly also provoking those who are all too aware of how things stand. They achieve this with with a dexterity that appears to have become so second nature to them that they appear unaware that they are doing so (possibly because most are at least bilingual and many Western educated).

This tension is felt more keenly when writing or publishing in English and the wrangle over how, or even if, to fault one’s own kind to the outsider audience — when feeling bitterly the need to do so to the insider — is dealt with adeptly, and in my view, essentially, by the writers in this collection.

Despite the soaring spirits of some of the characters who appear in Seeking Palestine, this is not an optimistic assessment of the current status quo. There is, as Karma Nabulsi points out, “no plan” as the Palestinians are forced to “accommodate an Israel bent on our destruction.” Palestinians are also, as Hiller, Shehadeh and Nabulsi point out in different ways, watching a revolution not only devour its children, but get rich while it does so.

Internal criticisms

Misha Hiller, whose experiences during the Lebanese civil war provide the insights for his award-winning novel Sabra Zoo, states this dynamic most bleakly: “this is where your freedom-fighting bedfellows with whom you shared a dream of liberation can become your enemies: when you realize that all they wanted was the freedom to exploit and oppress you themselves.”

Truths about the failings on the Palestinian side which cannot be said, as Ghassan Kanafani pointed out, in any way to justify the injustices meted out by the other side, are frequently encouraged to be suppressed for the greater good. Criticisms of leadership (both of the Palestinian Authority in Ramallah and the Hamas government in Gaza) are not altogether new to the Palestinian discourse. But what is fresh in this collection, which the variety of styles allows for, is the conveyance of beautifully-sketched examples of how justice and common humanity prevail despite the oppressive nature of occupation and the witheringly disappointing nature of leadership. To sound fey, I could call this spiritual. Or to be clichéd, just plain heart-warming.

Also coming with the criticism of political parties, there is a freeing up of voices keen to speak out against other societal ills and gripes, from hard-hitting portrayals of physical and sexual abuse where the lack of protection of the individual person serves as a metaphor for the state of the collective people (Abulhawa in her startlingly disturbing and deftly-written piece, “Memories of an Un-Palestinian Story”) to thinly-veiled personal disappointment at highly-admired fathers who allow “the cause” to prevail over the family (Abu-Lughoud).

Fun and revolution

The peculiar, but fascinating, relationship between fun and revolution is also touched on here, albeit in passing. Nabulsi refers to the “carnival atmosphere” and the “near celebratory sense of adventure” connected to her memories of being part of a revolutionary movement. Hammami wryly observes, when writing of organizing a party (New Years Eve, not political) that during the intifada, “we had humor, but not fun.” Abu-Lughod also recalls her father joking that during 1936 revolt, “It was all down with this and that … we never heard the word ‘up.’”

When the idea of “having fun” dominates the aspirations pedaled out by advertising agencies globally to encourage people to buy products, its motivating ability should not be underestimated. When Palestinian intifadas tend to, as Hammami also ironically observes, go on forever, the need for merriment and entertainment (through art or otherwise) is not to be dismissed. If the jokes about the Khalilis (Hebronites) had not made Driver Mahmoud’s passengers all snort with laughter, including the woman in full niqab covering, would they all have been as willing to push the car when it broke down? One gets the sense of resistance being expected and non-adherence to frequently inequitable requirements of leaderships being severely sanctioned (again Nabulsi) with few rewards — a multi-stick approach, without a carrot in sight.

If anything were to be faulted in this collection it could be the proximity of the writers to each other, in terms of representing a particular class, or having a West Bank (no Gaza voices, sadly), academic diaspora elite bias (with a disproportionate number of writers originating from Jaffa for some reason). But the work is of such a high standard, the themes so universal, the lightness of touch in dealing with the heaviest of subject matters so poignant that it, unlike many of its dignified characters and writers, is able to transcend all boundaries.

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this review erroneously attributed quotations to Mourid Barghouti’s work. The article has since been corrected.

All proceeds raised from Seeking Palestine will be donated to the Palestinian Festival of Literature www.palfest.org.

Selma Dabbagh is the author of the novel, Out of It (Bloomsbury, 2012) set between Gaza, London and the Gulf, that was chosen as a Guardian Book of the Year in 2011 and 2012.