The Electronic Intifada 1 July 2005

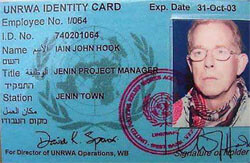

The identity card of UNRWA’s Jenin project manager, Iain John Hook of Britain, who was killed in the West Bank city of Jenin on 22 November 2002. The United Nations challenged Israel’s contention that Palestinians had fired at Israeli troops from a U.N. compound during a gun battle in which soldiers shot and killed Hook. (Reuters)

Despite more than 1,700 Palestinian civilians having been killed by the Israeli army in this intifada, according to figures from the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem, few soldiers ever account for those deaths. Only 90 investigations by the army have been held, leading to seven convictions of soldiers, three for manslaughter and none for murder. The longest sentence so far has been for 20 months.

The Hurndall family is under no illusions about the reasons for its success in securing the conviction of Sergeant Idier Wahid Taysir. “It has only come about because we are a British family, we have a very powerful and strong influence exerted on the Israel government through our own Foreign Office and embassy here, and the fact that we had put together our own case, collected the evidence, and proved to the Israeli government that this was indeed a crime,” said Anthony Hurndall. A lawyer, Mr Hurndall completed his own detailed investigations into his son’s killing in Rafah and compiled a 50-page dossier which contradicted the Israeli army’s version of events.

Journalist Jonathan Cook investigated a much earlier killing of a British citizen by an Israeli soldier, who has gone unpunished to this day. Iain Hook, a 54-year-old United Nations worker in Jenin refugee camp, was killed in cold blood by an Israeli marksman in November 2002. Both the Israeli army and the United Nations investigated the killing but the matter was quietly dropped by both sides, after the Israelis claimed that Hook was accidentally shot by one of their soldiers after Palestinian gunmen overran the UN compound.

A partial record of Cook’s investigation was reported by the British Guardian shortly afterwards. Here we reproduce a much fuller account of his revelations, written in December 2002 and which have never before been published. They suggest that the soldier who shot Hook knew he was targeting an unarmed civilian, and that he may have been seeking revenge for the deaths of Israeli soldiers during an invasion of Jenin camp several months earlier.

The Electronic Intifada hopes that, in the wake of the Hurndall judgment, Cook’s piece may reopen the file on Hook’s death - and help bring his killer to justice.

IAIN HOOK INVESTIGATION

By Jonathan Cook in Jenin, December 4, 2002

Two hours before Iain Hook, a 54-year-old Briton working for the United Nations in Jenin refugee camp, was killed by an Israeli sniper’s bullet in the back, he took a decision that possibly sealed his fate. In the explosively tense atmosphere of the camp on the morning of November 22 [2002], as gunbattles raged between Israeli soldiers and a handful of Palestinian gunmen in the area, he stepped out of the relative safety of the UN compound into the turmoil outside.

Witnesses who saw the incident say it looked like a foolhardy decision, as it in fact proved to be. What they did not know was that Hook was facing a virtual mutiny among his UN staff trapped inside the compound.

Hook, holed up with another British UN worker, Paul Wolstenholme, and 30 Palestinian staff, as well as two young camp children given sanctuary from the Israeli armour that rolled into the camp at 8am, had spent the morning desperately trying to persuade the army to call a temporary ceasefire with the Palestinian gunmen. He spoke repeatedly to the Israeli army’s local liaison officer, Capt Peter Lerner, asking for permission to evacuate the site. But as he told one witness: “Things are not going well.”

As the morning wore on, his control inside the compound started to slip.

A narrow alleyway - out of view of the Israeli army - runs along the northern and western flanks of the UN site, part of a maze of side streets running off into a local neighbourhood. It was a hiding place for Palestinian gunman confronting Israeli soldiers. The other two sides were controlled by the Israeli army. The eastern side of the compound is effectively sealed off by the wall of a large house belonging to the Selmar family, which was occupied by soldiers. And on the fourth, northern side armoured personnel carriers (APCs) patrolled the main street, overlooked by tall neighbouring houses in which Israeli snipers were stationed.

Effectively, when the army rolled in to this little corner of the camp, it had effectively chosen to place the UN compound and its staff in the middle of the confrontation between the Israeli soldiers and the Palestinian gunmen.

As it became clear that the Israeli army was not willing to cooperate with Hook, the parents of the children and the Palestinian families of the local UN staff gathered in the narrow alleyway along the compound’s southern wall, entirely shielded from the view of the army. They talked excitedly over the 8ft concrete wall to those trapped inside about how to get them out.

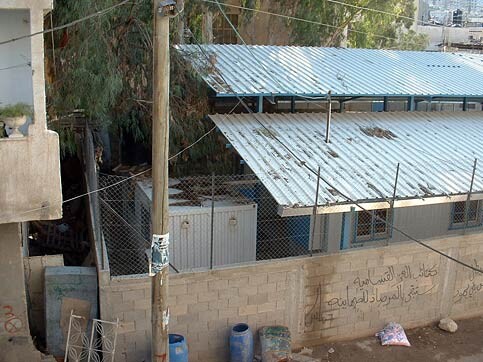

The northern wall of the UN compound in Jenin refugee camp. (Photo: Jonathan Cook)

The wall is topped by another 6ft of chainmail fencing but the attempt to smuggle anyone over the high concrete wall might have put them in view of the Israeli snipers on the other side of the compound. The consensus was that they should knock a small hole in the concrete wall. Hook was adamantly opposed to the idea. As well as the families outside the perimeter wall were armed Palestinian youths sheltering from Israeli gunfire. He argued that creating a hole in the wall would compromise not only the site’s neutrality but also its security.

By 11am he was losing the argument. Unable to win any concessions from Lerner via his cellphone, Hook decided to try to force the army’s hand by making a face-to-face appeal. The nearest soldiers were in an APC parked close to the northern wall of the compound, some 10 metres from the entrance.

Hook emerged cautiously at first, say witnesses, carrying aloft a blue UN flag, but once he had taken the decision he strode confidently towards the APC.

What occurred next happened too quickly for Hook to take evasive action. An armed Palestinian youth sprinted from a doorway in the alley running alongside the western wall of the compound towards Hook, stood behind him and let off a volley of bullets at the APC and the soldiers inside.

The incident lasted no more than a few seconds, and no one was hurt. The youth ran back into the alley and Hook quickly retreated into the compound and locked the gate. The soldiers’ response is less certain. It is possible that the soldiers in the APC fired into the compound. UN investigators are known to have removed part of a thick metal bar in the gate, said to be riddled with bullet holes, for forensic tests.

But the incident probably did far more damage than the physical harm to the gate. It is possible, given the speed of the attack, that some of the soldiers believed the gunman followed Hook out of the compound; a few may have even thought he fled back into the site with him.

It also had a context that Hook, who had arrived in the camp only a month earlier in October, may not have fully appreciated. His involuntary use as a human shield may have cemented an already hostile, if not poisonous, attitude towards the UN and its staff from Israeli soldiers, particularly those in Jenin, that has lingered since the April 2002 invasions of the West Bank.

It was during the invasion of Jenin that 23 soldiers were killed after they were lured into the booby-trapped heart of the refugee camp. The deaths, the biggest single blow to Israel’s army during the intifada, turned the refugee camp overnight into a byword among the military for “terror”.

And who was to blame for the venomous Cobra’s Head, as Jenin was soon nicknamed? Not Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Authority, which is not allowed to administer to the refugees, but the UN’s refugee wing, UNRWA. It was the UN’s long-standing indulgence of terrorism in the camps that had allowed the militants to gain such a foothold, army commanders and Israeli politicians were saying with one voice.

“Israelis forget that UNRWA has no security role in the Palestinian camps, ” said a diplomatic source. “There are a few internationals like Iain but the great majority of staff are doctors or teachers and they are all local people. They live in the camp too. For their own safety if nothing else they cannot be seen to be helping the army.”

In truth, most Palestinian UN staff, many refugees themselves and all victims of decades of Israeli military brutality, have a natural sympathy with the goal of the resistance movements, including the armed factions, trying to liberate the West Bank and Gaza from Israeli occupation.

There are two competing investigations under way into the killing of Hook, of Felixstowe, Suffolk. One is by his employer, the UN, and the other by the organisation responsible for his death, the Israeli army. Neither side is cooperating with the other.

Israel’s foreign minister Binyamin Netanyahu has promised his British counterpart, Jack Straw, that the army’s findings will be passed on to the British government. That report will be the first to hit the British foreign minister’s desk. It is expected in the next few days and major parts of it have already been leaked to the Israeli press. The army’s main contention will be that the compound was overrun with Palestinian gunmen and that they used the site to fire at Israeli positions.

It is a claim that has been strenously denied by the UN spokesman Paul McCann from the outset. He has called the army’s account “totally incredible”. UN investigators have been told by staff, including Wolstenholme, the other Briton in the compound, that no gunmen ever entered the site.

The army has indicated how it will substantiate its claim. It has released a recorded message left on Lerner’s phone from Hook timed at 12.53pm, some 20 minutes before he was shot. The message runs as follows: “Hi Peter, it’s Iain here. I’m just making a progress report, really. We’re pinned down in the compound. The shabab [an Arabic word used to refer to young men or fighters] have knocked a hole in the wall, which I’m not happy about at all. I’m trying to keep them out, and I will just keep my people pinned down in the corner until I hear from you. OK? Over.”

The army will argue that this message proves that Palestinians wanted, and did, enter the compound. But the truth is rather different.

When Hook returned to the UN site after the shooting incident outside, the threatened mutiny quickly became a real one. The local staff and their families, helped by youths (shabab), including possibly some of the gunmen, started making a hole in the wall. Neighbours brought out hammers and screwdrivers to help them.

It is unclear when the hole was completed. One witness, Caoimhe Butterly, a 23-year-old Irish peace activist, says she saw it being worked on at about noon. At some point, possibly about 12.30pm, it was large enough for an evacuation. The female UN staff and the children left through the hole but Hook managed to restrain his male staff. He warned that they would be indistinguishable from the gunmen in the alley and would be potential targets for Israeli fire.

The recorded message hints at the solution Hook devised. He agreed with the army that he and his staff would stay “pinned down” in the north-eastern corner of the compound, in view of Israeli sniper positions. A metal awning covers the whole compound, severely restricting the view in and out. But the Israeli marksmen, located across the main street on the second and third floors of the home of 75-year-old Tawfik Farhad, had a good view of that corner.

The UN staff stayed seated on the ground but Hook moved around. He returned to the hole and argued with the youths in the alley to leave the area because they were jeopardising the evacuation of the site. Some time shortly after his 12.53 call to Lerner he succeeded. We know because he rang the UN field office in Jerusalem at 1.10pm - five minutes before he was shot - to tell them that all the youths had left the area.

In fact there was little incentive for the Palestinians to have entered the compound, even had they wanted to. The wall of the Selmar house adjoining the UN site has one small window under the compound’s awning. It gives an almost complete view of its interior. The army had requisitioned the house and could have stationed a sniper at the window at any point, as the local Palestinian gunmen would surely have known. Strangely, given its story now, the army never chose to do so.

The UN investigators have been told by a series of witnesses that there was no gunfire around the compound for some “tens of minutes” before Hook was shot. He was holding his mobile phone, possibly making a call to Lerner or the field office, his back to the sniper, when he was killed. The army says the phone was mistaken for a pistol or grenade.

Wolstenholme, who came immediately to Hook’s aid, has told the investigators that he could see the red light of the sniper’s laser sights aimed on Hook’s body. He looked up and clearly saw the face of the soldier who fired from the third-floor window, only 25 metres away.

The view into the north-eastern corner of the UN compound from the third floor of Tawfik Farhad’s home, the spot where an Israeli sniper was positioned. He shot and killed Iain Hook as the UN worker stood under the awning. (Photo: Jonathan Cook)

The UN’s investigators are said to be “more than puzzled” by how the sniper, at close range and using telescopic sights, failed to identify Hook, more than 6ft tall, pale with reddish hair. He did not look like a Palestinian youth. And from the third floor window the sniper must have been watching Hook’s movements for some time.

There are many more unanswered questions. If there were gunmen in the UN site firing at Israeli positions, why is there no bullet damage around the windows of Farhad’s home, given that they were just about all that could be seen by someone inside over the compound’s high concrete walls?

And how could the Israeli sniper possibly have thought that Hook, or a gunman for that matter, was endangering his life? Even if the marksman mistook the mobile phone for a grenade, how could he believe the figure holding it intended to throw it out of the compound? Facing an 8ft concrete wall topped by a chainmail fence and a metal awning, a grenade would simply have rebounded. The act would have been suicidal.

And if Hook had agreed with Lerner that he and his men remain in the north-eastern corner on the compound, under the watch of the Israeli snipers, how did the marksman who shot Hook not know that he was firing into an area where there were civilians?

All the indications so far are that the army report, the one Straw will see, will fail to answer these questions. That just leaves the UN report, not expected now for some weeks. Hopes are diminishing that there is any mood in the senior echelons of the UN for a battle with Israel or America over the report.

The earlier UN investigation into claims of a massacre of Palestinians in the refugee camp, where more than 50 Palestinians died, largely fizzled out under US pressure, says a diplomat. And the report published months later, which included accusations of Israeli war crimes, was not pushed hard, the source adds.

“Much of the UN’s funding comes from Washington, and UNRWA needs good relations with Israel and its army if it is to continue doing its work in the refugee camps,” said another source close to the investigation. “That day’s events were embarrassing for everyone. The question is whether the UN has the nerve this time to rock the boat.”

Jonathan Cook is a journalist whose work has appeared in the Guardian, International Herald Tribune, Al-Ahram Weekly, and other newspapers. Based in Nazareth, Cook is an occasional contributor to EI. He is currently writing a book on the Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Related Links