Palestine Report 13 January 2005

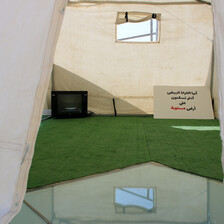

A 55-year-old Palestinian man is turned away from a polling station in occupied East Jerusalem (Photo: Aaron/ISM)

For a myriad of reasons, not nearly as many people as could heeded the call in East Jerusalem. According to official statistics provided by the Central Elections Commission on January 10, only 26,365 out of 120,000 eligible voters in the occupied eastern sector of Jerusalem cast their votes for the next president of the Palestinian Authority on January 9.

No doubt, Israel’s omnipresence in a city Palestinians regard as the future capital of their state put a damper on the overall atmosphere. Just 20 kilometers and two Israeli checkpoints away in the West Bank city of Ramallah, flyers urging citizens to vote for this or that candidate scattered the streets and walls were plastered from top to bottom with smiling hopefuls. In Jerusalem, a few scrappy posters of presidential candidates were pasted sporadically throughout East Jerusalem - in some places they had been torn down by Israeli authorities and replaced by willful loyalists - but no Palestinian flag was to be seen or loud rally heard in the city streets.

From the start, Israeli authorities banned any campaigning in the city, arresting presidential candidate Mustapha Barghouti twice for being in Jerusalem without “the proper permits.” Only after international pressure did the West Jerusalem municipality allow for 15 billboards to be placed in East Jerusalem for candidates to “legally” put up ads and posters.

“The Israelis are frightening people in different ways,” says Ziad Hammouri, head of the Jerusalem Center for Social and Economic Rights. “There are many rumors swirling that voting could harm your rights in Jerusalem and people are intimidated.”

Indeed, Israeli authorities took actual steps to compound these fears. Longtime Fateh activist in Jerusalem, Nasser Qous was arrested and questioned for several hours on January 2 by Israeli police and border guards who raided a Fateh youth club in East Jerusalem.

“They told me that campaigning for Abu Mazen was against the law,” he said. “They said they would put the club under observation and monitor those who come or go and would arrest them or confiscate their ID cards.”

Intimidation and rumors aside, the actual voting arrangements for East Jerusalemites have been harrowing enough. Styled on the model of the 1996 PA elections, Israel allowed only 5,376 people from East Jerusalem to vote in Israeli post offices throughout the city. Palestinian polling centers were banned - six registration centers were promptly shut down by Israeli authorities at the start of voter registration in September - and the actual voting was carried out under the discreet but watchful gaze of Israeli security. The remaining eligible voters were forced to cast their ballots in polling centers in West Bank towns on the outskirts of the city. This raised fears that those who ventured out of Jerusalem to vote would not be allowed back through the numerous checkpoints and gates in the separation wall that so sharply divide Israeli-controlled Jerusalem from Palestinian areas.

But even voting within Israel’s self-declared Jerusalem municipality borders proved to be highly problematic for many. Voters criticized the fact that ballots were cast in envelopes that were then ferried in ballot boxes to Ramallah for tallying. “How do we know where our votes really went,” asks Khader Khader, a professional translator and East Jerusalem resident. “And why aren’t the international observers paying any attention to this fact?”

Khader had gone to the central post office on the morning of January 9. After his name was checked against a list at the door, he was allowed in. But when Khader returned to the post office after casting his vote to complain about the procedures, he found the international observers were just as surprised. “I asked an observer from [former US President Jimmy] Carter’s delegation where the ballot boxes were,” he explains. “He had no idea.”

Even before election day, the apparently hushed up Palestinian-Israeli agreement on East Jerusalem - many officials felt the deal was unsatisfactory - was the cause of internal disputes, which climaxed in a petition published in the main Arabic-language daily, Al Quds. On January 8, one day before election day, a half-page add appeared in the newspaper with a long list of names of prominent East Jerusalem personalities including Ziad Hammouri, Hanan Ashrawi and Archimandrite Attallah Hanna, calling on Jerusalemites not to bow to Israeli measures by voting in Israeli post offices. Rather, they said, voting should only be conducted in proper polling centers outside of the city.

Hammouri was furious. “First of all, my name was on that petition and I was not even consulted. Secondly, people should vote no matter what the circumstances.”

Mahdi Abdel Hadi, director of the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, agreed that Jerusalem’s vote was extremely crucial even if the PA still does not have any political clout over the city. “Palestinians want to maintain their identity and heritage in Jerusalem as Palestinians, and to this end they should register and choose a Palestinian representative. I hope there is a big turnout.”

The turnout, as it was, was not as big as many had hoped. Still, according to official CEC statistics, over 16,000 of the 26,365 people who cast their ballots in Jerusalem voted for Mahmoud Abbas. Anyone who was at the Abbas campaign rally in Bir Nabala north of Jerusalem on January 7 would have already anticipated this outcome.

Waving and smiling to chants of “Abu Mazen will lead those who strive for liberation,” the Fateh candidate who later garnered over 62 percent of the votes, swore that one day “we would all march on Jerusalem.”

It was no coincidence that he began his campaign speech before the hundreds of people who came out to hear him on the chilly winter day, with a Quranic verse about Jerusalem and the Aqsa Mosque. Abbas had earlier said he would not go to Jerusalem with other presidential candidates because he would not accept entering the city under the Israeli occupation. “We are not in Jerusalem today, but tomorrow we will go, because it is the eternal capital of Palestine,” he told the crowd roaring with applause.

His campaign manager and former advisor to late President Arafat, Tayeb Abdel Rahim played the “Jerusalem card” as well, appealing to the strong sentiments that the mention of Jerusalem always invokes.

“January 9 is the day of Jerusalem,” he told the crowds after Abbas had finished. “We call on Jerusalemites to vote to show the world that Jerusalem is the eternal capital of Palestine.”

And although the voter turnout among East Jerusalemites indicated that not everyone was of this opinion, others said this was their chance to show their Palestinian colors in a city where such expressions are largely suppressed by a strangulating Israeli occupation.

“I want to exercise my right to vote and choose a leader,” said Iyad Muna, co-owner of the Educational Bookshop in Salah Eddin Street. “The Palestinian cause concerns me more than any actions by the Israelis.”

Just a couple hundred meters down the road at the Automatic Grocery, Abu Yahya was less enthusiastic. “What did the PA ever do for Jerusalem? Nothing.” Still, this East Jerusalem businessman’s bark is worse than his bite. After declaring his disappointment with the candidates and the PA’s previous perceived indifference towards Jerusalem, Abu Yahya pulled out his voter registration slip. “I still registered” he admits, “but if I vote, it is only because I am a Palestinian in Jerusalem.”