The Electronic Intifada 24 April 2024

Despite the destruction of Gaza, hope must be retained.

APA imagesChemotherapy is a necessary evil.

A friend of mine – who survived cancer – told me that.

Chemotherapy kills every cell within you, cancerous or not. It doesn’t spare any cells in your body.

Since I began treatment for cancer, I have become thin. And I feel vulnerable.

I am focused on a battle for survival. And I am not backing down in the face of cancer.

Instead, I am pushing through the pain. Telling the world my story is part of my battle.

I will never stop telling the world about how Israel has killed people that I loved. They included my dear friend Mohammed Hamo.

Nor will I stop telling the world how Israel has destroyed the dreams of people who are still alive.

When I got out of Gaza during the current genocide, I initially promised myself never to return there. The difficulties I faced living in Gaza were enormous.

Before Israel launched its war in October, Gaza’s unemployment rate was among the world’s highest.

It was extremely challenging for young graduates to find a job that offered sufficient income to sustain a family and meet basic needs like food.

I had experienced life outside Gaza previously as I had traveled abroad. Ukraine (to which I traveled three times between 2012 and 2018), Turkey and even Egypt were incomparable to Gaza – which was accurately described as an open-air prison.

Even before the current war began and my diagnosis with leukemia, I had already planned to leave Gaza without returning.

The current war has changed me to the core – especially after my teacher Dr. Refaat Alareer was assassinated in December.

When I finished my third year at university, something bittersweet dawned on me. Despite achieving good grades, I longed for more classes with Dr. Refaat.

I used to ask him whenever I saw him, “Is there a chance you’ll teach us another course? I really miss your classes.”

“Who knows?” he would reply. Whether he could teach us more was a matter for his department at the university and its planning, he would explain.

At the start of my fourth year, I visited Dr. Refaat’s office and asked him for advice. I was applying for a scholarship and wanted to know what I should write in a motivation letter.

“Never forget to mention Palestine and share our culture with others in any program you’re going to apply for,” he said.

“Read more”

Dr. Refaat repeatedly told me that I was a “smart and brilliant student.”

“But you don’t read enough,” he added. “You must read more.”

I could spend an hour discussing anything and everything with him. He never failed to answer my questions; he was full of knowledge.

Literature classes had a reputation for being boring in our university. A lot of information would be discussed but it would focus on something narrow – mostly historical content.

The classes taught by Dr. Refaat were the opposite of boring.

Students didn’t dare to blink during his lectures as they were afraid of missing a piece of information they hadn’t heard before.

His lectures overflowed with knowledge. In a 50-minute poetry class, he would analyze each line in such depth that the ensuing discussions were mindblowing.

Dr. Refaat always encouraged us to be creative, to think outside the box. His methods of teaching were distinctive.

Throughout his courses, Dr. Refaat went beyond the curriculum to enrich our knowledge with lessons on various aspects of writing, history, culture, religion, translation and most importantly Palestine.

I never saw a professor use memes as a method of teaching. He loved memes.

He made us love them too. Sometimes we would feature him in our memes and he would love that.

He always told us to come to class without doing any research on the next poem. We would just read the poem and discover it in the class.

It was difficult for him to do so. He would be teaching a poem to students who lacked knowledge that could help in understanding or appreciating it.

Sometimes he would be mad at us.

It was not easy for us to understand an entire poem when we hadn’t done any prior research on it.

But Dr. Refaat believed in keeping things fresh. He never gave up shaping our creativity.

He would reward those who were creative. Only Dr. Refaat’s students knew how hard it was to get a bonus mark from him.

I will never forget his facial expressions when he gave me one. He would say things like “wow” and “excellent.”

It wasn’t the extra mark that made me happy. I was happy because I had made Dr. Refaat feel happy.

Other students had told me that was impossible.

Making Dr. Refaat proud and happy encouraged me to think outside the box.

Dr. Refaat kept writing even in the brutal nights of the current genocide.

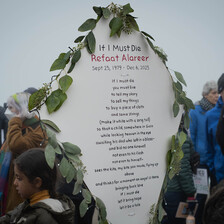

He pinned his poem “If I must die” on his Twitter account, reflecting on what people should do after his death and what message they should carry: hope.

He loved teaching the works of William Shakespeare. And he believed in the immortality of literature.

He always believed that when writers die, their words will never die with them. Eventually he became a story himself, an immortal one.

He did not die in vain. He changed my personality and my perspective on life.

I was one of Dr. Refaat’s students. And I am proud to say that I still am one of his students.

Always be brave

Although Israel killed him, Dr. Refaat continues to inspire me and all the people who knew him.

Even with him gone, he is still teaching me.

He is teaching me how to always be brave.

He is teaching me that words are powerful. They defy death.

He is teaching me to be generous, and offer help to others even in these times when I need help myself.

It has been six months since I was diagnosed with leukemia. My hematologist told me that my treatment will take two and a half years.

I am now determined that I will return to Gaza once my treatment is finished.

My home was partly destroyed in October. If it is not fully repaired by the time my treatment is over, I will live in a tent.

I will return to continue Dr. Refaat’s mission: Never stop writing or encouraging other people to write about Palestine. I will return to tell his story and the story of my friends who were killed by Israel.

When Israel killed Refaat, it created millions of Refaats.

Each one of his students is now a Refaat. Each one of his friends is a Refaat.

Everyone who loved him and still loves him is a Refaat.

We will honor him by continuing his mission. We will honor him by being the voices of Palestine.

Khaled El-Hissy is a journalist from Jabaliya in the Gaza Strip. Twitter: @khpalestined